The Roman Empire, the heart of ancient civilization, was not immune to economic crises. While it stood as a champion of architectural, military, and political achievements, it faced a series of economic crises that affected its stability and longevity. Economic crises were often the results of a combination of factors, including political instability, military overspending, social strife, and widespread disease. These economic crises were characterized by political chaos, military turmoil, and economic disruption.

Financial troubles in Ancient Rome often had cascading consequences. Epidemics like the Antonine Plague, which decimated the population, and currency debasement by emperors like Diocletian strained the empire’s economy. Furthermore, the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD marked the end of an era catalyzed by relentless invasions and internal decay. These economic crises illustrate the complex interplay between governance, economic policy, societal issues, and external pressures that shaped the trajectory of Rome’s imperial economy.

Key Takeaways

- Economic crises in the Roman Empire were many-sided, involving disease, debased currency, and sociopolitical disruptions.

- The Crisis of the Third Century highlights the vulnerability of Rome to concurrent military and political challenges.

- The longevity of the Roman Empire was significantly impacted by a series of financial downturns and reforms.

Causes of Economic Crises

The debasement of currency played a substantial role in the financial crisis, as emperors such as Aurelian and Diocletian sought to address fiscal shortages by adding more base metals to the silver denarius. This practice led to inflation, reducing the purchasing power of the currency and destabilizing the economy. This became the favorite way of dealing with economic crises for most of the rulers in the Middle Ages.

Military anarchy also contributed significantly to the empire’s economic difficulties. The constant state of violence and upheaval discouraged trade and agricultural production, factors crucial for the Roman economy, resulting in shortages and soaring prices of goods.

The Plague of Cyprian further compounded these economic issues. This deadly pandemic decimated a significant portion of the population, including the workforce, leading to a decline in both production and consumption.

Lastly, the issue of succession impacted heavily on the Roman economy. The failure to establish a stable method for the transfer of power often resulted in civil wars and power struggles that damaged infrastructure and disrupted economic activity.

The synergistic effect of these facets – political instability, debasement of currency, inflation, military anarchy, assassinations, and succession crises – exemplifies the multifaceted roots of economic crises that the Roman Empire encountered, particularly during the turbulent Third Century.

The Crisis of the Third Century (235-284 AD)

During the third century, the Roman Empire faced a profound period of turmoil that nearly led to its collapse. Between 235 and 284 AD, a series of challenges fundamentally shook the Roman economy.

Invasions, internal power struggles, and epidemic diseases, combined with severe financial deficits, plagued the empire. Hyperinflation became a critical issue as emperors repeatedly reduced the silver content in coins, undermining the currency’s value.

Military overstretch and civil conflict further worsened the situation. Constant warfare demanded high military expenditures, and the frequent leadership changes destabilized the political structure. This period saw over 20 emperors, most of whom ascended through military coups rather than hereditary succession.

The economy additionally suffered from labor shortages brought about by the plague, which decimated the population and, thus, the workforce. This led to a decline in agricultural productivity and trade, both vital for economic stability.

The devaluation of currency and resource scarcity triggered price hikes, complicating trade and commerce. Barter systems increasingly replaced currency-based transactions as trust in the coinage eroded.

By 284 CE, the Roman Empire emerged profoundly changed, setting the stage for successive reforms under Diocletian. Despite these challenges, the Roman state managed to endure, demonstrating its resilience in the face of multiple overlapping crises.

The Antonine Plague (165-180 AD)

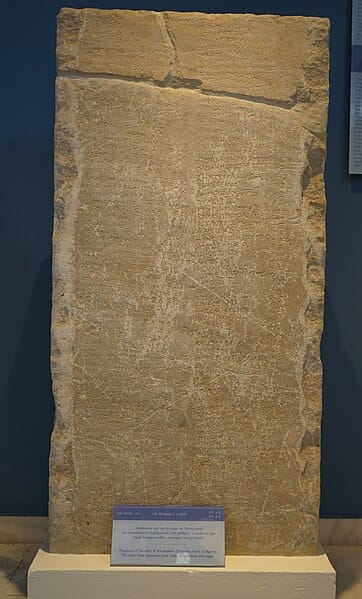

Source: See page for author, CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

During the mid-2nd century, the Roman Empire was struck by a devastating epidemic, historically recorded as the Antonine Plague. Originating between 165 and 180 AD, this plague precipitated one of the most severe economic crises in the empire’s history.

The pandemic, which may have been smallpox or measles, had far-reaching consequences for Rome’s economy. A sharp reduction in the population led to a scarcity of labor across various sectors. Agriculture, the backbone of the Roman economy, was particularly hit hard. The shortfall in the workforce meant that many farms could not maintain their production levels, leading to a decrease in food supply and subsequent inflation in prices.

Moreover, tax revenue plummeted as the number of taxable citizens reduced. Rome’s military was not immune to the pandemic’s effects either, facing both a drop in troop numbers and the financial strain of supporting a widespread and battle-ready force without sufficient money.

This health crisis, while primarily a human tragedy, intensified existing socioeconomic tensions and pushed the Roman Empire into a state of financial strain that would resonate through the following years. Lack of manpower affected not just the agricultural sector but also the army and urban workforce, contributing to the overall economic decline.

The Antonine Plague stands as a stark example of how a pandemic can profoundly disrupt the economic stability of even the most formidable of empires, highlighting the inseparable link between population health and economic vitality.

The Currency Debasement under Diocletian

During the late third century, the Roman Empire faced severe inflation and general economic instability. Emperor Diocletian introduced a series of reforms in an attempt to restore economic balance. One of his notable initiatives was to address the debasement of currency, a practice that had undermined the economic foundations of the empire.

Despite intentions to reform the economy, Diocletian’s policies often worsened existing financial problems. The debasement of currency – the reduction in precious metal content in coins – had already been an ongoing problem, leading to a loss of confidence in the monetary system. Diocletian persisted with the issuance of coins with reduced silver content, further eroding trust in the empire’s currency.

In addition to the debased coins, Diocletian is known for his Edict on Maximum Prices, an ambitious attempt to curb inflation by fixing the maximum prices for goods and services throughout the empire. Although groundbreaking, the edict failed to achieve its goals due to the already diminished value of the currency and the impracticality of enforcement.

Source: TimeTravelRome, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The inability of Diocletian’s currency reforms to stabilize the economy is considered one of the top economic crises of the Roman Empire. The continued circulation of debased coinage highlighted the limitations of imperial economic interventions and the challenges in managing a complex and expansive economy in antiquity.

Diocletian’s era stands out as a critical point in Rome’s monetary history. His reforms were pivotal, yet they laid bare the difficulties in controlling inflation and maintaining a consistent economic policy across the extensive Roman Empire.

The Collapse of the Western Roman Empire (5th Century AD)

The ultimate demise of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD was the consequence of multiple profound economic crises. The empire’s heavy reliance on enslaved workers stifled innovation and resulted in a stagnant economy, unable to adapt to changing circumstances. Furthermore, oppressive taxation to fund military campaigns led to a widespread financial burden among the populace.

Trade Networks and Disruption: As instability grew, the once great trade networks that sustained the Roman economy began to fracture. The disruption of these networks, vital for the movement of goods and wealth, was harmed by repeated invasions by Germanic tribes. These groups not only looted land and disrupted trade but also diverted trade routes permanently, further isolating the western provinces economically.

Internal Strife: Political strife within the empire further eroded economic stability. Successive imperial administrations failed to implement necessary reforms, leading to the devaluation of currency and hyperinflation. As power struggles ensued, administrative efficiencies collapsed, and confidence in the empire’s fiscal strength was weakened.

Barbarian Invasions: The continuous incursions by so-called barbarians placed an extraordinary strain on Rome’s military resources. The expenses to counter these threats drained the imperial coffers and affected other critical sectors of the economy. This relentless pressure contributed to the economic deterioration that was instrumental in the empire’s collapse.

The economic disruptions of the Western Roman Empire were intertwined with and compounded by barbarian invasions and internal chaos, leading inevitably to the decline and fall of the western provinces.

The Financial Crisis of the Late Republic (1st Century BC)

The 1st Century BC marked a period of economic tumult for the Roman Republic. Extensive military engagements drained resources while contributing to a gap between the wealthy elite and the average citizen. Political maneuvers deepened these issues, reflected mostly in the factions that competed for power at various times. These factors set the stage for one of the top economic crises in Roman history.

Economic instability was further heightened by widespread land appropriations under the guise of reforms, which often badly affected many Roman citizens. The agricultural sector suffered due to a reliance on imported grain, which led to shortages and price instability, affecting the urban population significantly. Additionally, the periodic practice of proscriptions-public declamations leading to confiscations of property and executions-undermined economic confidence.

Civil strife compounded these challenges, as the Republic was in a series of internal conflicts. This period witnessed a double effect: direct financial losses due to the war efforts and the related erosion of economic stability, which sowed the seeds of discontent among the populace. Consequently, financial institutions faced crises of liquidity and solvency, hinting at the systemic fragility of the Republic’s economy.

This era of economic strain culminated in the embrace of the imperial model, as persistent crises required a structural change in governance and economic management. The conjunction of these factors during the late Republic is integral to understanding the economic landscape that widened the Roman crisis and the key transition toward an Empire.

Economic Policies and Reforms

Throughout the tumultuous periods of the Roman Empire, several emperors implemented critical economic policies and reforms to counteract crises and stabilize the economy. Some of these reforms were directly related to the economic crises that preceded the reforms.

Diocletian’s Economic Reforms

Emperor Diocletian, ruling from 284 to 305 AD, saw the Empire hard-pressed by inflation and economic disarray. To address the devaluation of currency and neutralize the economic crises, Diocletian enacted sweeping reforms. Prominent among these was the Edict on Maximum Prices in 301 AD, setting price caps on goods and services to curb rampant inflation. Though ultimately unsuccessful in controlling prices, the edict was a bold attempt to enforce economic stability.

Diocletian’s reign is also noted for the introduction of a new tax system, which sought to streamline tax collection and make it more equitable. This system was based on rigorous census taking to assess the wealth of Roman provinces, ensuring a more regular and reliable flow of revenue to the central government.

Introduction of the Tetrarchy

The Tetrarchy, meaning “rule of four,” was an innovative administrative system introduced by Diocletian to manage the vast Roman Empire more effectively. The Tetrarchy divided the Empire into four segments, each ruled by a tetrarch. This division aimed at better management of provincial resources and to provide a more robust and responsive leadership during economic crises.

The economies of these subdivisions were closely linked, and collective strategic policies, including revised tax laws and consistent military spending, aided in the stabilization of the Empire’s economy. The tetrarchs worked in concert to ensure that the division of power did not compromise a unified economic strategy across the Empire.

Constantine the Great and Economic Rejuvenation

Constantine the Great, ascending to power after Diocletian, is often remembered for his religious influence; however, his economic reforms also left a marked footprint on the Roman Empire. One significant measure implemented by Constantine was the introduction of the solidus, a gold coin that became the standard for Byzantine and European currencies for more than a millennium. Its introduction provided a stable and universally accepted medium for transactions, strengthening the Empire’s internal and external trade.

Furthermore, Constantine altered the composition of the Roman provincial system to optimize tax collection. This reorganization enabled more efficient governance and fostered economic rejuvenation, as provinces could more effectively collect and contribute taxes due to more accurately represented populations and economic capabilities. Constantine’s vision cast a lasting legacy upon Rome’s economic infrastructure, proving him to be a key figure in the history of the Empire’s economic policies and reforms.

For You:

Tell us what you think, which one was the worst economic crisis in the Roman Empire?

People Also Ask:

What were the primary economic crises that led to the fall of the Roman Empire?

The primary economic crises that led to the fall of the Roman Empire included the debasement of currency, over-reliance on slave labor, overexpansion, and military overspending. This created a weakened economic state unable to sustain the vast territory of the empire, which caused economic crises.

How did overexpansion contribute to Rome’s economic crises?

Overexpansion stretched Rome’s resources thin and made it difficult to manage such a vast territory effectively. The maintenance of expanded borders demanded significant military and financial resources, which strained the empire’s treasury and undermined its economic stability.

In what ways did reliance on slavery impact the economic crises and society of Rome?

Reliance on slavery in Rome suppressed technological innovation and agrarian reform due to the abundance of cheap labor. It also contributed to social unrest, as the non-slave population struggled with unemployment and the destabilization of social structures. All that led to economic crises.

Can you outline the major economic problems faced by the Roman Republic?

The Roman Republic faced many economic crises, yet economic problems such as wealth inequality, corruption, and land concentration in the hands of the elite were the biggest reasons for that crisis. Additionally, repeated wars and conquests disrupted the agrarian economy, leading to increased reliance on imports and a decline in self-sufficiency.

What were the central causes of the economic crises, especially in the Roman Empire during the 3rd century?

There were several economic crises, but the economic crisis of the 3rd century, known as the Crisis of the Third Century, was predominantly caused by political instability, military anarchy, and the consistent threat of barbarian invasions. These factors undermined the empire’s economic foundations, leading to hyperinflation and resource depletion.

Which factors were instrumental in weakening the economy of ancient Rome?

Factors that weakened the economy of ancient Rome and caused economic crises included trade deficits, depletion of gold and silver mines, an outbreak of plagues, and a decline in agricultural productivity. This economic fragility was exacerbated by a lack of fiscal and monetary policies capable of addressing the empire’s complex challenges.

Hello, my name is Vladimir, and I am a part of the Roman-empire writing team.

I am a historian, and history is an integral part of my life.

To be honest, while I was in school, I didn’t like history so how did I end up studying it? Well, for that, I have to thank history-based strategy PC games. Thank you so much, Europa Universalis IV, and thank you, Medieval Total War.

Since games made me fall in love with history, I completed bachelor studies at Filozofski Fakultet Niš, a part of the University of Niš. My bachelor’s thesis was about Julis Caesar. Soon, I completed my master’s studies at the same university.

For years now, I have been working as a teacher in a local elementary school, but my passion for writing isn’t fulfilled, so I decided to pursue that ambition online. There were a few gigs, but most of them were not history-related.

Then I stumbled upon roman-empire.com, and now I am a part of something bigger. No, I am not a part of the ancient Roman Empire but of a creative writing team where I have the freedom to write about whatever I want. Yes, even about Star Wars. Stay tuned for that.

Anyway, I am better at writing about Rome than writing about me. But if you would like to contact me for any reason, you can do it at [email protected]. Except for negative reviews, of course. 😀

Kind regards,

Vladimir