Period: AD 193 – 337

Second Crisis of the Empire

AD 193 – 194

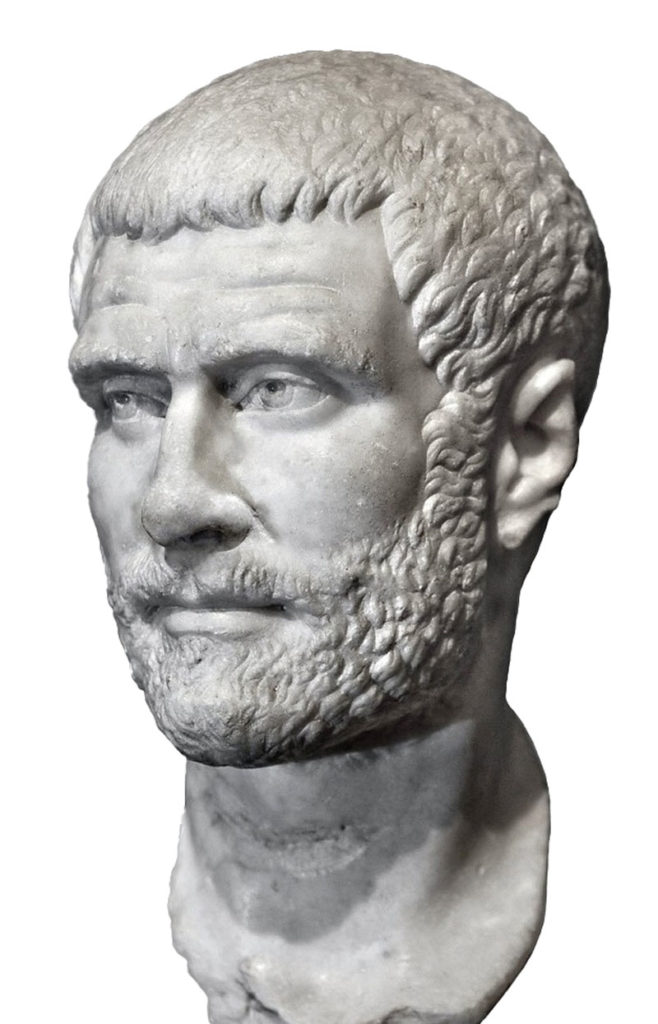

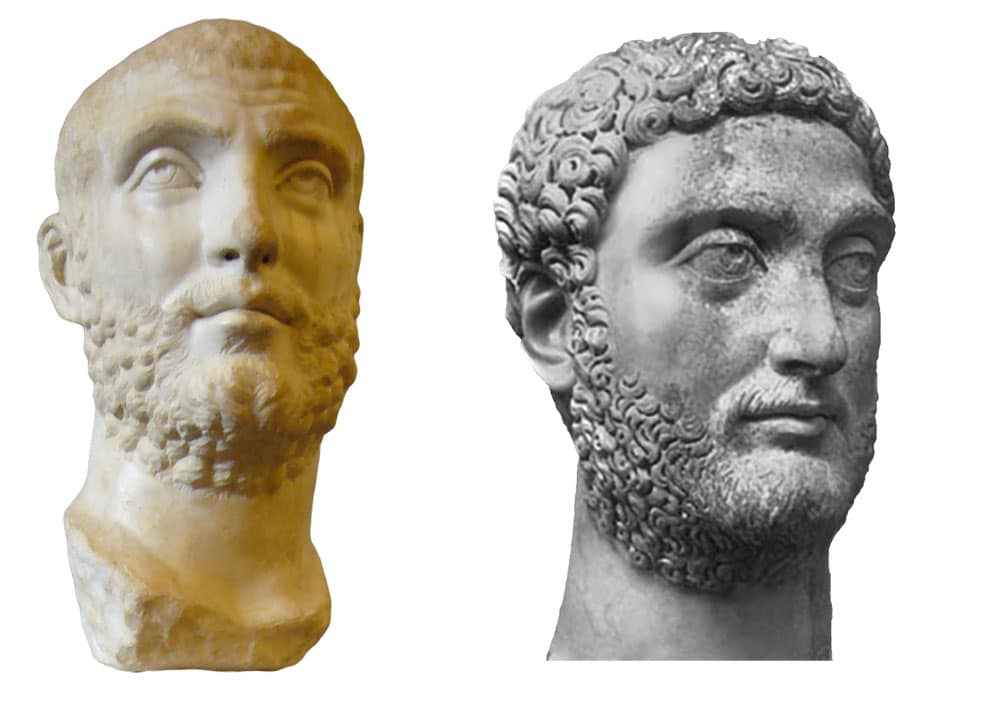

Publius Helvius Pertinax – “Pertinax”

Reign: AD 193

Whatever the nature of the conspiracy against Commodus, it brought to office in his place a better man, Publius Helvius Pertinax, prefect of Rome and former governor of Britain; but only temporarily, as an ominous pattern of events unfolded such as had followed the death of Nero.

Pertinax, an old soldier was made emperor by favour of the praetorians and their prefect. He lost that favour because in a conscientious effort to rectify the mistakes of Commodus and the evils which had sprung up during his rule, he tried to tighten discipline instead of relaxing it.

He lasted for a mere three months, until the praetorians mutinied, broke into the palace, murdered Pertinax, paraded his head through the streets on a pike, and offered the imperial throne to the highest bidder.

Pertinax reign might have been a short one. But it formed an enormously important precedent. Pertinax is understood to be the first ‘Soldier Emperor’ or ‘Praetorian Emperor’. They were raised to the throne by the provincial legions which they commanded and ruled only till ejected and killed by another soldier who seized the succession.

Marcus Didius Severus Julianus – “Julianus”

Reign: AD 193

The winner of a bizarre auction held by the praetorian guard to establish the imperial succession was Didius Salvius Julianus, an elderly senator.

Rome might have needed to accept the dictate of the praetorian guard, but the provincial armies had a preference for a chief of their own selection.

The legions in Britain and on the Rhine chose Clodius Albinus, the army in Syria proclaimed Pescennius Niger, the troops on the Danube hailed Septimius Severus.

Rome was the necessary objective. Helpless it lay waiting to be conquered by its own legions.

Albinus was a sluggard, a glutton, commanding little respect among his men. Pescennius was popular in the east, but his army had least experience of fighting. Severus was a hard soldier at the head of hardened troops, – and, being in Pannonia, he was nearest Rome.

Neither Albinus nor Pescennius was ready to strike. Severus marched on Rome.

Emperor Julianus alternated between empty threats and desperate offers of compromise. Severus ignored both. As he drew near, the praetorians, inexperienced in war and realizing themselves totally inferior to the advancing troops, deserted to Severus who, in order to save himself trouble and time, had no trouble making promises which he had no intention of keeping.

As he reached Rome on 10 June AD 193, no resistance was offered.

Didius Julianus was stripped of his imperial office and put to death on the orders of the senate.

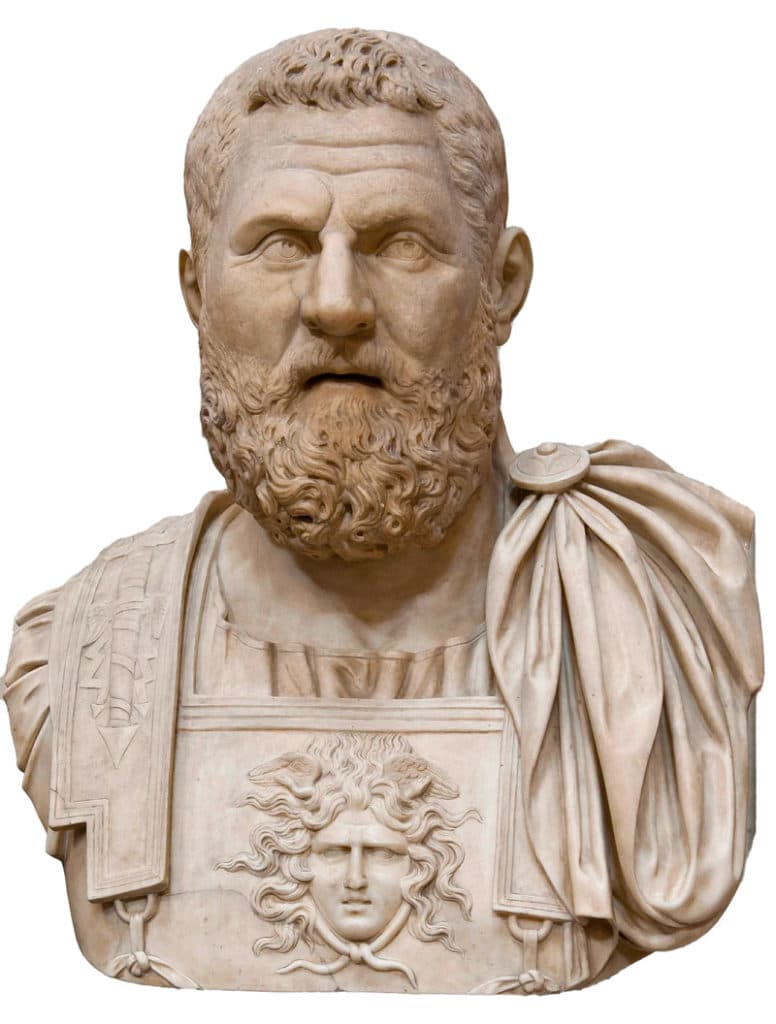

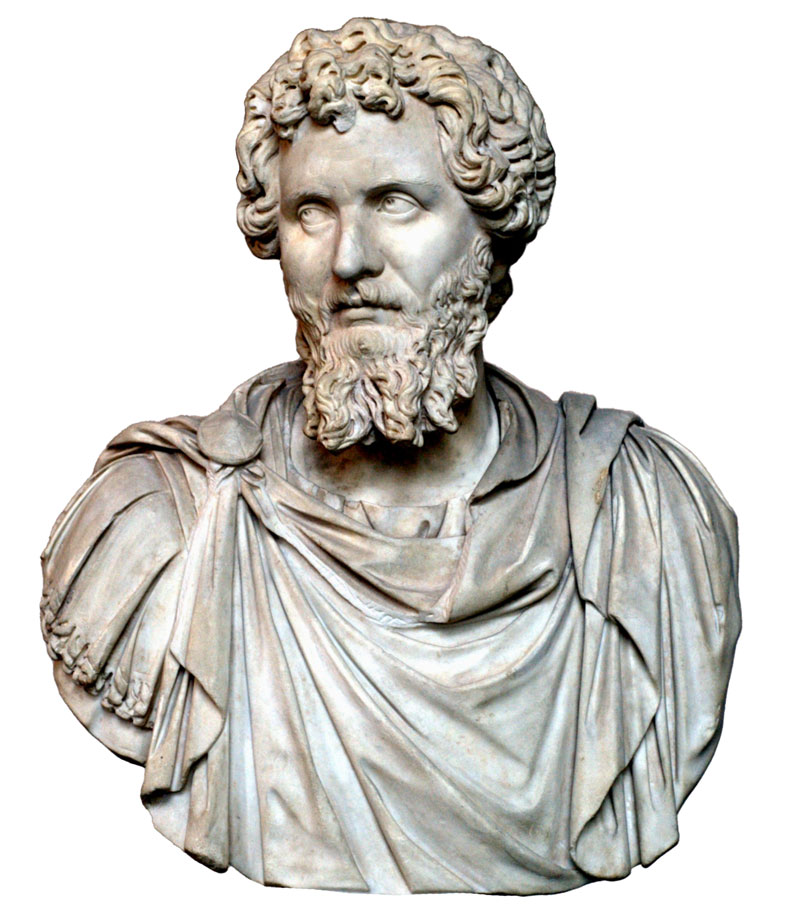

Lucius Septimius Severus – “Severus”

Reign: AD 193 – 211

Having disbanded the imperial guard and replaced it with a force 50’000 strong, from men of his own legions, Severus set about coming to terms with his two rivals, Pescennius Niger in Syria and Clodius Albinus in Britain. This he finally did in a most conclusive fashion by defeating them in turn: Niger at Issus in AD 194, and Albinus at Lugdunum in Gaul in AD 197.

Severus did not understand himself as fully established till he had inspired wholesome fear in the minds of any potential rivals by dooming several senators to death. Much because the rude soldier was accepted with reluctance by a body which still looked upon itself as the supreme constitutional authority.

In the years immediately before his accession Severus had held command on the most dangerous of all the Roman assignments, the banks of the river Danube. There he had learnt that the empire’s need was defence, not aggression. But so too, that the aggressive barbarians needed to be kept in healthy awe of the Roman power. Severus was not far from being a barbarian himself. Grim, hard, unscrupulous, he lacked any statesmanly qualities, and yet he was free from wanton cruelty or vindictiveness. In his own, crude ways Severus commanded the empire as he had once commanded his troops as a general.

The domestic administration he left to competent and worthy officials, spending his own time among the armies on one or another frontier.

It was probably in Severus’ time that the prefect of Rome, whose function was primarily military, was invested also with the main jurisdiction in matters of criminal law in and within 100 miles of the city, and the commander of the imperial guard, a military office, with similar jurisdiction over the rest of Italy and the provinces. After the fall and execution in AD 205 of Fulvius Plautianus, who had performed the latter duty with rather too much authority, Severus appointed in his place a noted legal expert, Aemilius Papinianus (d. AD 212). Within the army itself, the top jobs went to those with the best qualifications, not necessarily those of the highest social rank. Severus improved the lot of the legionaries by increasing their basic rate of pay to match inflation (it had been static for a hundred years), and by recognizing permanent liaisons as legal marriages – up until then a legionary was not allowed to marry. It was probably Severus, too, who improved the status of the ordinary soldier by extending the civil practice to allow veterans to style themselves honestiores (men of privilege) as opposed to humiliores (men of humble rank). As the distinction between citizens and non-citizens became eroded, so this new form of class-discrimination developed, which included separate punishments for the same crime.

Whereas humiliores could be sentenced to hard labour in the mines, honestiores were merely banished for a short term. The most common form of punishment for a minor offence was flogging, from which honestioreswere immune. Severus’ philosophy of rule, was to pay the army well and to take no notice of anyone else. By ‘anyone else’ he meant, of course, the senate.

A professional soldier, Severus favoured those with the greater military experience to maintain the empire’s frontiers in the east in the face of the marauding Parthians, and spent the last two and a half years of his life in Britain fending off the menaces of the northern tribes.

By unremitting hard work Severus restored and increased the security and prestige of the empire, which had been reduced in the days of Commodus.

But the desire to found a dynasty led him at last to the very blunder into which Marcus Aurelius had been drawn, as he let the imperial succession fall into the hands of his unsuitable son Bassianus, better known as Caracalla.

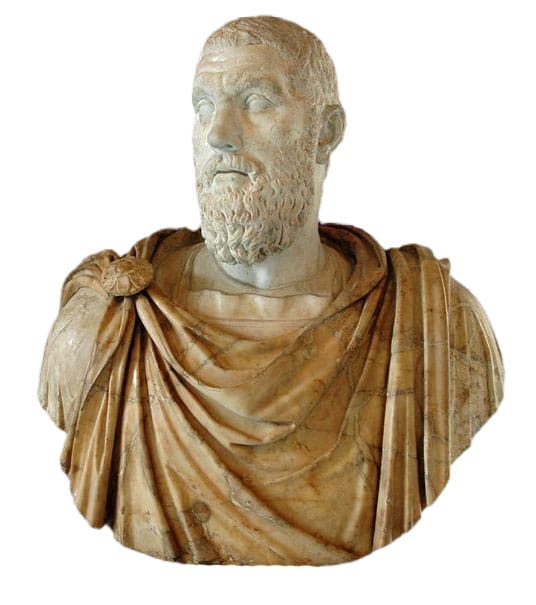

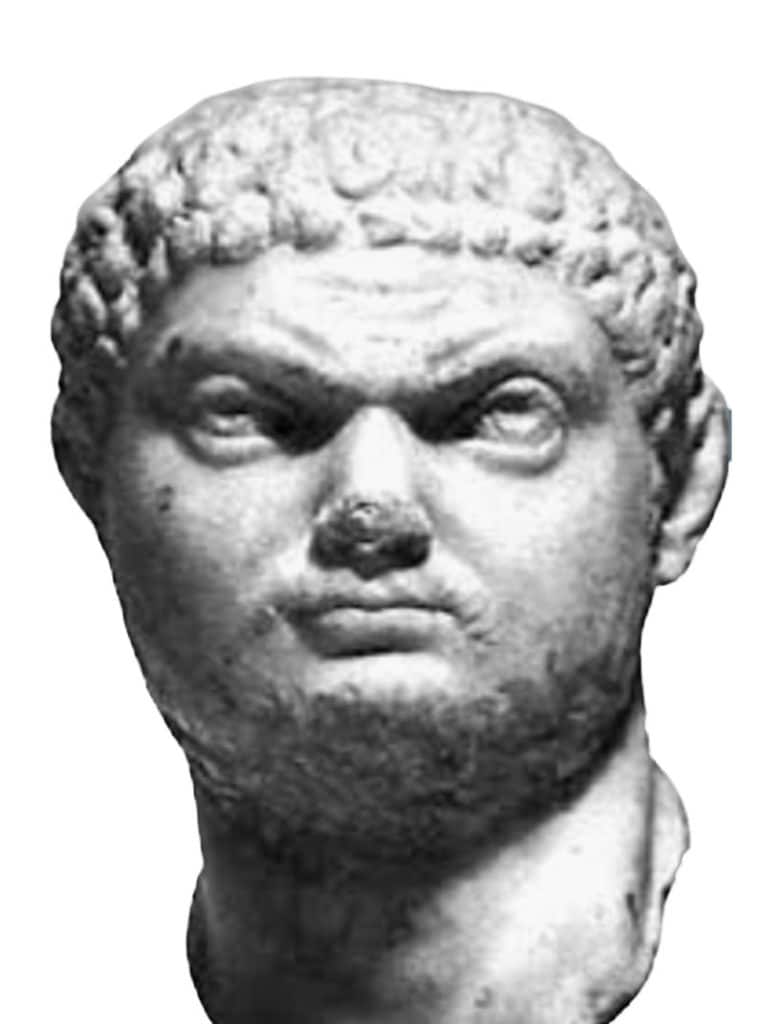

Lucius Septimius Bassianus – “Caracalla”

Reign: AD 211 – 217

Publius Septimius Geta – “Geta”

Reign: AD 211

Severus had two unruly sons, Caracalla (AD 188-217) and Geta (AD189-212), whom he had nominated to rule jointly after him. Caracalla (a nickname – it means a Gaulish greatcoat) resolved that aspect of the arrangement by murdering his brother, and kept faith with his father’s advice by increasing the pay of the army by 50 per cent, thus initiating a financial crisis.

Some sources suggest that it was to get more taxes to repair this crisis that he granted full citizenship to all free men in the Roman empire. Wether or not that is so, it is to Caracalla in AD 212 that is attributed this final step in the process of universal enfranchisement which had begun in the third century BC.

Caracalla in one swoop did away with the surviving distinction between provincials and citizens.

Though, the murder of his brother, was only the beginning of a continuous display of savagery by a tyrant. On his travels through the eastern provinces this was only further confirmed as, for a today unknown insult to his dignity, Caracalla had thousands of the population massacred.

These things were endured because he bought the good will of the soldiery by relaxation of discipline and lavish donations and increase of pay, both at the expense of the civil population as well as of military efficiency. While attempting to extend the eastern front Caracalla was murdered in Mesopotamia in AD 217, by a band of discontented officers who preferred their own candidate, Macrinus, commander of the imperial guard since Caracalla had done away with Papinianus.

(Papinianus, after Caracalla had murdered his brother, was ordered to ‘play down’ the crime on his behalf in the senate and in public. He responded that it was easier to commit fratricide than to make excuses for it.)

Marcus Oppellius Macrinus – “Macrinus”

Reign: AD 217 – 218

Macrinus, whose guilt in the assassination of Caracalla was at first undetected, achieved elevation to the imperial throne, since there was no obvious rival. But he was no soldier, and lacked both the abilities and the character to maintain the position. Once a rival emerged his fate was sealed. Though Macrinus was accepted by the senate, he never actually got to Rome. He continued the eastern war, only to be defeated and killed the following year by detachments of his own troops in Syria, who supported a 14 year old supposed son, but actually a distant cousin, of Caracalla who was known as Elagabalus.

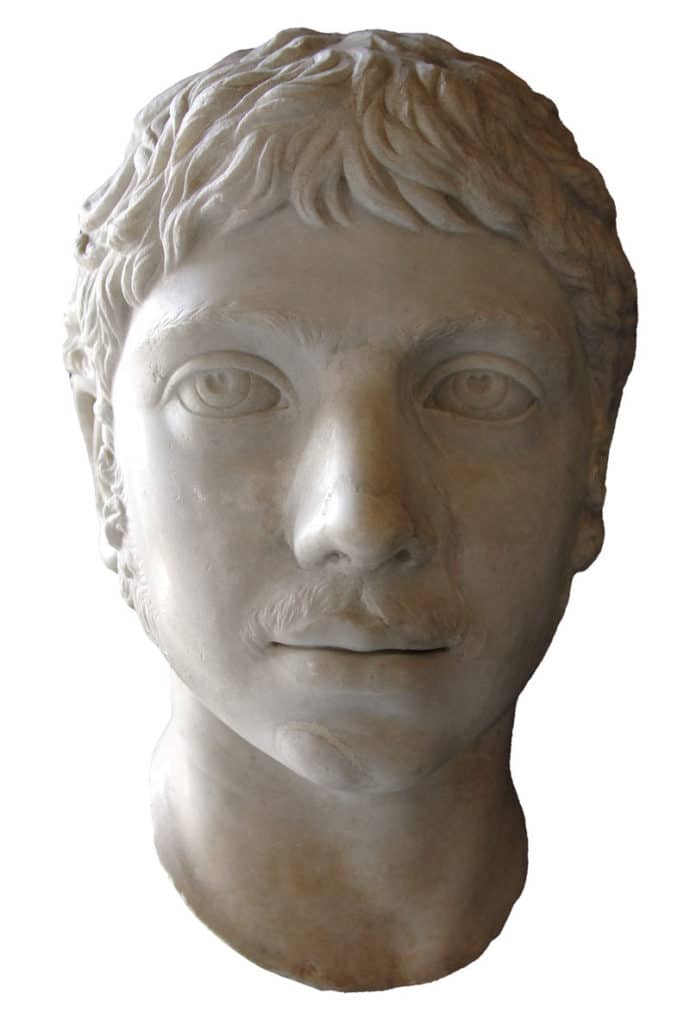

Varius Avitus Bassianus – “Elagabalus”

Reign: AD 218 – 222

There were no descendants of Severus, but there were his sister-in-law Maesa and her daughters Soaemias and Mamaea.

These Syrian women were ambitious and Soaemias and Mamaea had sons, Bassianius and Alexander Severus.

The elder of the two boys had been made high priest of the Syrian sun god Elagabal at Emesa. To win over the soldiery, his mother and grandmother did not scruple to spread the story that Caracalla was his father.

The actual involvement of Macrinus in the death of Caracalla was becoming known and the soldiery suspected their new emperor sought to curtail their privileges they had enjoyed under Caracalla. Hence the troops had ample reason to rid themselves of their ruler, only there was an alternative. The existence of Elegabalus gave them just this alternative, however dubious his supposed dependency was.

The bulk of the troops in Syria were easily incited to rise in the name of Caracalla’s son. Macrinus was overthrown in a battle outside Antioch and the young high priest to an exotic Syrian god became Augustus of the Roman empire.

The reign was a vast orgy of the most extravagant and monstrous luxury and unspeakable vices. The only redeeming feature in it was the comparative absence of sheer blood-lust. In Rome the obscene rites of Oriental deities superseded those of the western pantheon.

Even after making every allowance for the exaggeration of shocked moralists or the inventive capacity of political enemies, what remains is still a picture of a totally decadent, if not depraved emperor, totally alien to all things Roman.

Maesa no doubt very soon realized that her second grandson Alexander represented the only possibility of her continuing power.

Pains were made to make Alexander Severus personally popular with the soldiery, who were sickened at the depravities of Elagabalus.

As it became evident that a jealous Elagabalus sought the death of Alexander Severus, the praetorians were driven to invade the palace, slay Elagabalus and proclaim the Alexander Severus emperor.

Marcus Julius Gessius Alexianus – “Alexander Severus”

Reign: AD 222 – 235

That a 16 year old could take office as emperor of the Roman empire and rule for thirteen years with more than moderate success was due partly to the fact that he was a sensible, likeable lad who knew his limitations and was prepared to take advice, and partly to his mother, Julia Mammaea, who recognized who would give the soundest advice.

The historians are full of praises of the virtues of the young emperor, the restoration of tranquility, the revival of prosperity which had suffered grievously from the merciless and capricious taxation imposed to meet the extravagances of the two last reigns.

Probably the controlling spirit of government for some years was Mamaea, who exercised a supreme influence over the son, whom she trained and guided.

In the civil administration Alexander was guided by a selected council of state.

But the problem of effective control was rendered for him more difficult than it had been for the Antonines, through the failure of military discipline an the insubordination of the rank and file of the soldiery for which Caracalla was mainly responsible.

Alexander owed his throne, probably his life, to the praetorians who therefore deeply resented any attempts to curb their powers and privileges. The young emperor in person led Roman armies on one great campaign against the eastern power which now again bore the Persian instead of the Parthian name. Trajan at the beginning, and Cassius Avidius in the second half of the second century had struck heavy blows against the long formidable Arsacid power. Severus also had conducted a vigorous campaign against the Parthians. But now the Arsacids had been swept away by a Persian chief, the founder of the Sassanid dynasty, who assumed the old Persian name Ardashir (Artaxerxes) and was bent on nothing less than the recovery of the old Persian empire. He deliberately challenged Rome, telling its emperor to withdraw from Asia. Alexander took up the challenge.

The emperor returned from the campaign to report to the senate of great victories won against immense odds. It seem clear however that the honours on the whole rested with the Persians, despite suffering heavy defeats in battle, had not in fact lost any territory.

While it would appear that the personal prestige ofArdashir was enhanced, Alexander’s failure to sufficiently impress a soldiery already disposed to mutiny was fatal.

Alexander had scarcely returned to Rome when he was summoned to the northern frontier to deal with the German hordes.

In AD 235 the soldiery mutinied and Alexander and his mother were both set upon and murdered at the fortress town of Mainz.

Gaius Julius Verus Maximinus – “Maximinus Thrax”

Reign: AD 235 – 238

Marcus Antonius Gordianus Sempronianus Romanus – “Gordian I”

Reign: AD 238

Marcus Antonius Gordianus Sempronianus Romanus – “Gordian II”

Reign: AD 238

The murder of Alexander Severus was certainly the work of Maximinus, a giant of a Thracian peasant who had risen through the ranks to become commander of the imperial guard. He now nominated himself as emperor, doubled the pay of the army, and continued the German campaign at its head. Maximinus enormous strength and almost incredible powers of endurance had already attracted the attention of Severus thirty before. This mighty barbarian had sufficient enough intelligence to win and to justify his promotion. The soldiers believed that they had found a leader who was one of their kind, one to whose discipline and command they would readily submit.

For the moment the sheer brute force of this giant was irresistible. For three years, remaining himself with his army on the Rhine or the Danube, Maximinus ruled the empire. This in turn meant that he disposed of anyone whose ambition, character of abilities he feared. While all over he empire he robbed the cities of their public funds and stripped temples of their treasures, stamping out resistance by ruthless massacre.

Eventually things came to a head in the province of Africa. The people slaughtered an imperial official charged with the business of collecting the exorbitant taxes and persuaded their own elderly prefect to assume the throne, very much against his own will in AD 237. This new emperor, Gordian I, immediately associated with himself his scarcely less reluctant son.

The Gordians made haste to report these proceedings to the senate, submitting themselves to its decision as the constitutional authority. The senate responded by confirming their election and declaring Maximinus Thrax a public enemy.

But meanwhile the commander of Mauretania fell upon the Gordians and slew them.

Decimus Caelius Calvinus Balbinus – “Balbinus”

Reign: AD 238

Marcus Clodius Pupienus Maximus – “Pupienus”

Reign: AD 238

On receiving the alarming news of the death of the two Gordians the senators, who could hope for no mercy from Maximinus, elected two of their own number as joint emperors, Balbinus and Maximus. Though they were also forced by the angry city mob to further associate the new emperors with a very youthful Gordian III who became Caesar.

Maximinus Thrax though still had to be reckoned with. After some delay he was now moving down from the northern frontier upon Italy, and the armies which could be hastily gathered had little hope of defeating his experienced troops.

Maximinus, passing the Alps, found before him a denuded country, and a strongly defended fortress in Aquileia. He began to besiege it and his troops began to starve. With no food they became mutinous and murdered their chief.

The senatorial revolution was apparently complete. the joint emperors set about an honest attempt to place the government on an orderly basis and restore the discipline of the army, which very soon mutinied again, cut them to pieces and declared the thirteen year-old Gordian III sole emperor.

Marcus Antonius Gordianus – “Gordian III”

Reign: AD 238 – 244

Though he was only 13 at his accession, Gordian III, with the help of a capable regent, enjoyed civil and military success until the regent Timesitheus died of an illness. Timesitheus’ successor though Philippus was considerably less noble-minded and strove from the very beginning to undermine and eventually murder the emperor he was charged to protect.

Gordian III was murdered in Mesopotamia in AD 244 as a result of Philippus’ plotting while collecting wild animals to take part in his triumphal procession in Rome for his victories in Persia.

Marcus Julius Verus Philippus – “Philippus Arabs”

Reign: AD 244 – 249

Philippus Arabs’ reign was remarkable mostly for several revolts against him. Had he achieved his position by treachery against Gordian III, whom he reported to the senate as having died of illness, he possessed little moral authority with which to command the loyalty of the troops.

Philippus initial action was to make peace with Persia, to allow him to head for Rome and secure his throne.

In AD 245 he led a campaign against the Carpi and Quadi who had crossed the Danube and after a two year struggle successful forced the barbarians to sue for peace.

This success no doubt improved his standing, allowing him enough popular support to try and create a dynasty by making his son, also named Philippus, co-Augustus.

Yet the question of his own leadership was far from settled among the military, not to mention his son’s accession.

The first rebellion was that of a certain Sibannacus on the Rhine, shortly afterwards followed by Sponsianus on the Danube. These revolts were brief and easily dealt with.

And yet early in AD 248 some of the legions on the Danube nominated Pacatianus as emperor. In turn the trouble among the Romans only further encouraged the Goths who now crossed the Danube and wrought havoc in the northern provinces.

Worse still, in the east of the empire the legions now hailed a certain Iotapianus emperor.

So dire did the situation grow, Philippus became convinced the empire was falling apart and offered his resignation to the senate.

Though one senator, Decius, responded to the emperor’s address to the senate that all was far from lost and that Philippus should remain in office. When his estimation that both challengers would no doubt soon fall victim to their own mutinous troops came true, it was Decius himself who at the end of AD 248 was dispatched to the Danube to restore order among the mutinous soldiers.

In a bizarre turn of events the Danubian troops, so impressed by their leader, proclaimed him emperor in AD 249. Decius protested he had no desire to be emperor, but Philippus gathered troops and moved north to destroy him.

Left with no choice but to fight the man who sought him dead, Decius led his troops south to meet him. In September or October of the AD 249 the two sides met at Verona.

Philippus was no great general and by that time suffered from poor health. He led his superior army into a crushing defeat. Both he and his son met their death in battle.

Gaius Messius Quintus Decius – “Decius”

Reign: AD 249 – 251

After Decius’ victory over Philippus Arabs at Verona, the senate made haste to confirm his election as emperor (AD 249).

Decius then still maintained, perhaps quite truthfully, to have accepted the decision of his soldiers to make him emperor against his will.

He would seem to have been a man of ability and character who was genuinely resolved to make worthy use of the power which had been thrust on him.

He proposed to restore the state by a revival of the old Roman virtues. The first steps to that end were to appoint an honoured and distinguished senator, Valerian, to the long obsolete office of censor, and a zealous return to the pristine worship of the ancient gods of Rome.

In turn this brought about a sharp but short persecution of the Christians, who had been undisturbed since the days of Marcus Aurelius.

But action of another kind was immediately necessary. The menace on the middle and lower Danube was greater than it had ever been before.

In AD 250 Decius was summoned to the Balkans by the news that a vast Gothic horde, supplemented by fighting men of various non-Gothic tribes, had swarmed over the Danube and was ravaging the Roman province of Moesia.

He found them engaged in besieging the fortress of Nicopolis, On his approach they broke off their siege and instead went on to attack the much more important stronghold of Philippopolis. Decius pursued them, the Goths then suddenly turned, surprised his army and defeated it, thereafter continuing onward to Philippopolis which fell after stubborn resistance.

Decius however reorganized his army, blocked the passes, cut off the Goths’ way out of the Balkans and threatened them with destruction.

He was determined to deal them nothing less than an annihilating blow and at last he very nearly succeeded.

Both sides knew that the stake was all or nothing. In the great battle of Forum Trebonii, the emperor’s son was slain before his eyes, but the first line of Goths was shattered, so too the second.

But the front of the third was covered by a bog in which the imperial legions, pushing on to complete the victory became hopelessly entangled, so that they were cut to pieces, emperor Decius perished with his soldiers (AD 251).

Gaius Vibius Afininus Trebonianus Gallus – “Trebonianus Gallus”

Reign: AD 251 – 253

The disaster of Decius’ defeat and death was terrific, but not without precedent. What was to follow however was even more ominous. Decius had realized that the Goths were foes who for the safety of the empire must be broken utterly and at all cost. Trebonianus Gallus, the successor chosen by his own soldiers was of a different mould than Decius.

Most likely to be able to return to Rome and secure his throne Gallus made a very unpopular peace with the Goths, allowing them to retire from Roman territory with all their booty and prisoners, and promising to pay them an annual subsidy.

Had Gallus won a peace which lost him the respect of many of his soldiers, then it wasn’t long before the Goths broke it anyhow. Within only a few months the Goths and their allies were pouring into Illyria. Aemilianus, the commander of Lower Moesia, flung himself upon them and utterly defeated them. Having so redeemed Roman honour in the eyes of his troops and many other Romans, he then claimed the imperial throne for himself.

Leading his forces into Italy he took Trebonianus Gallus completely by surprise. The few troops Gallus could muster were utterly inferior in both numbers and quality to the hardened Danubian troops of Aemilian.

And so Gallus’ desperate troops killed their own emperor at Interamna in order to escape slaughter (AD 253).

Marcus Aemilius Aemilianus – “Aemilian”

Reign: AD 253

The senate had barely time to confirm Aemilian as the new emperor, before he was in turn overthrown a few months after his victory.

Valerian, nominated three years earlier to the office of censor by Decius, had been sent to command the armies on the Rhine. Gallus had called for him to come to his aid, when Aemilian’s troops arrived, and yet the call had come too late.

Valerian had started out for Italy, but his emperor was dead before he arrived. But Valerian, once roused, did nor turn his troops around, but far more marched on, determined to overthrow the usurper.

Aemilian started out from Rome and moved north with his troops, to face off the invader. But history repeated itself, and Aemilian was slain at Spoletium by his own troops in order to avoid a fight (AD 253).

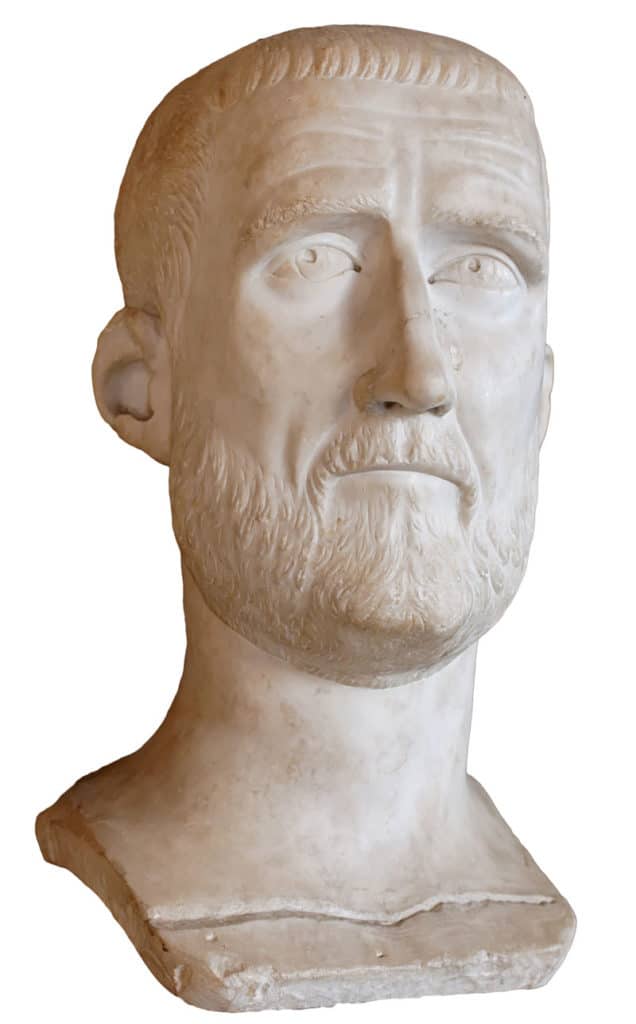

Publius Licinius Valerianus – “Valerian”

Reign: AD 253 – 260

At teh death of Aemilian, Valerian assumed the throne, beginning a seven year reign which brought fresh disaster. With himself he associated his son Gallienus. The guardianship of teh German frontiers was placed in the hands of his son and colleague, together with the able soldier Postumus, who achieved several victories over the Franks and Alemanni. While Gallienus was engaged in teh west Valerian plunged into disaster in the east. Persian aggression was still a huge threat to the empire under its leader Sapor (Shapur). Sapor turned his arms on Armenia, aving first taken the precaution of having the Armenian king Chosroes assassinated. Armenia fell an easy prey to Sapor, who captured the Roman fortresses of Carrhae and Nisibis. Valerian marched his troops toward Edessa in Meopotamia to relieve the siege of the city, but suffered heavy losses. Seeking to come to terms with Sapor he was asked to attend a personal meeting with the Persian king, who at this encounter simply had him taken prisoner and taken to Persia, where he died in captivity. Valerian’s army was trapped and forced to surrender.

Publius Licinius Egantius Gallienus – “Gallienus”

Reign: AD 253 – 268

After the disastrous capture of Valerian, the Persians swept devastatingly over Syria, even capturing Antioch, gathering spoils and captives but without thought of setting up an organized dominion.

The Roman generals Macrianus and Callistus managed to rally what was left of Roman forces to halt Sapor’s advance at the battle of Corycus, forcing the Persians to retreat behind the Euphrates.

Macrianus then masterminded a rebellion, placing his two sons, Macrianus and Qietus on the throne as join eastern emperors. But these efforts of setting up an eastern empire were to be crushed by an unlikely ally of emperor Gallienus. From Palmyra, on the border of the Syrian desert, emerged prince Odenathus who should defeat Quietus at Emesa and put an end to the rebellion. Thereafter the prince of Palmyra, Odenathus, staged an effective campaign against the Persians which gained him the command of the east by the now sole emperor Gallienus. He used his powers well, harassing the Persian withdrawal all the way back to the Euphrates river.

Meanwhile Gallienus in the west had to deal with an unfailing crop of challengers to his title. The worst such rebellion being that of Postumus, who successfully managed to break away several western provinces from the empire (The Gallic Empire).

In the east Odenathus eventually died in AD 267, leaving his title of commander of the east, to his famous wife Zenobia.

Then in AD 268 a massive Gothic invasion of the Balkans took place, the barbarians attacking in such huge numbers, they overwhelmed the Roman frontier defences.

Supported by the vast fleet of the Heruli, over 300’000 Goths broke into Thrace and Macedonia.

Gallienus greatest moment arrived when he marched east, prevented the sack of Athens and defeated the great barbarian army at the great battle of Naissus, the bloodiest battle of the entire third century.

Though his plans of following up his great victory and driving the remaining Goths back over the Danube were quashed as news reached him of the rebellion of Aureolus at Mediolanum (Milan). He returned to Italy and laid siege to Milan, only to be assassinated by a conspiracy involving the praetorian prefect Heraclianus and the two future emperors Claudius Gothicus and Aurelian.

The Gallic Empire

AD 260 – 274

For a brief time, caused by the weakened state of the empire, the western provinces managed to break away from Rome, creating their own independent state, known as the Gallic empire.

Marcus Aurelius Valerius Claudius – “Claudius II Gothicus”

Reign: AD 268 – 270

Claudius Gothicus, who had been among the leaders of the conspiracy against Gallienus.

He was the choice of the army to succeed the murdered emperor and was soon after confirmed by the senate.

Claudius Gothicus would make no terms with the besieged rebel Aureolus and did not interfere when the senate sentenced him to death.

the title Gothicus in the emperor’s name is attributed to have been won in his many engagements with Gothic armies and marauders as he set about the task which had been denied Gallienus, that of driving the Goths out of the Balkans after their crushing defeat at Naissus.

(The victory over the Goths at Naissus was for a long time mistakenly believed to have been achieved by Claudius Gothicus.)

Though not all should go well for Claudius Gothicus. In AD 269 Zenobia, queen of Palmyra, who had inherited the title of supreme commander of the east, broke with her alliance to Rome and began her conquest of the eastern provinces of the empire.

Was Claudius still busy with the Goths, and had he also learnt of further troubles with the Jutes (Juthungi) at the borders of Raetia, he simply could not deal with the threat arising from Palmyra.

Yet, Claudius was not to be the man to lead the Roman armies either against the Jutes, nor against Zenobia. A plague broke out in his camp to which he succumbed in AD 270, whilst making preparations for a campaign against the Jutes.

Marcus Aurelius Quintillus – “Quintillus”

Reign: AD 270

Quintillus was the brother of Claudius Gothicus and the story of his brief succession is mainly that of two conflicting claims of Claudius Gothicus’ last will. Did he claim that his brother had made him his successor and was he the preferred choice by many in the army, then Aurelian, Claudius Gothicus’ comrade in arms and highly respected general claimed he had been chosen to succeed.

For a brief time Quintillus, recognized by the senate as the rightful emperor, contested Aurelian’s claim. But soon he found himself completely abandoned, as everyone turned to Aurelian more through fear than by choice, and he committed suicide.

Lucius Domitius Aurelianus – “Aurelian”

Reign: AD 270 – 275

The threat of the empire being overrun from several directions at once was temporarily averted by Aurelian (AD 214-275), who became emperor in AD 270. In addition to evacuating the Roman garrisons in Dacia, he defeated the Alemanni, who on this, their fourth invasion of Italy, had got as far as Ariminum.

Though never since Hannibal had any foreign foe thrust so near to the heart of Italy. So threatening had the situation been that Aurelian was moved to raise a new wall of defence encircling Rome.

The overthrow of the Alemanni, following the treaties with the Goths, seemed to promise a long period of security on the Rhine and Danube frontiers. Though there remained beyond the borders of the empire the insolent Persian king, still unpunished for the devastation he had wrought and the humiliation he had inflicted. But before that matter could be taken in hand, there was still the task of reuniting the empire itself, which had had several provinces torn from it by Postumus during his revolt against Gallienus.

Tetricus, by now the fourth successor to Postumus, was still ruling these renegade provinces known as the Gallic Empire.

though in truth this self-styled Gallic emperor was only anxious to be relieved from a situation where he was anything but master. It would have cost him his life at the hands of the soldiery to openly submit to Aurelian. And yet the battle of Châlons is believed by many to have been little more than a token show of defiance, in which Tetricus quite gladly saw his troops defeated in order to be able to relinquish his position.

Then Aurelian’s attention turned to the east of the empire.

In the east Zenobia, following Odenathus, not only claimed for herself the command of the east, as bestowed on her late husband, but was in fact recognized throughout the east and in Egypt, which owed to Palmyra their preservation from the Persians.

The abilities first of Odenathus and then of Zenobia, aided by the wisdom of the philosopher Longinus, had given protection and restored order and prosperity without aid from Rome.

Dispatching his lieutenant Probus to Egypt to take control there, Aurelian himself led the imperial troops against Palmyra.

Zenobia offered valiant but vain resistance. Palmyra itself was besieged and captured. Zenobia herself was taken prisoner at her attempt to flee. along with Tetricus the captive queen was displayed in the magnificent triumph in Rome which celebrated the victories of Aurelian and the restoration of the empire.

The pride of Rome and the emperor being satisfied, the emperor displayed mercy by granting the fallen monarchs their lives.

It now finally remained to deal with Persia. A great expedition to that end was organized and under way, when Aurelian fell victim to a conspiracy.

He was murdered (AD 275) still in the fifth year of his reign, which had been a succession of triumphs. His murderers were not to be rebels but people among his staff who feared deserved or undeserved punishment.

Marcus Claudius Tacitus – “Tacitus”

Reign: AD 275 – 276

Tacitus was the immediate successor of Aurelian. With barbarian invasions befalling the empire on many fronts, Tacitus decided that it was the east which required most urgent attention and led his armies into Asia Minor (Turkey), where he alongside his brother Florian, defeated a large Gothic invasion force in spring AD 276. Though already by July of AD 276 Tacitus was dead, either due to natural causes or by assassination.

Marcus Annius Florianus – “Florian”

Reign: AD 276

Forian acceded to the throne immediately after his brother’s death, though within only two or three weeks Aurelian’s lieutenant Pobus, challenged his rule and soon after their armies marched on each other. Though Florian’s troops eventually mutinied, killed their leader and declared allegiance to Probus.

Marcus Aurelius Equitius Probus – “Probus”

Reign: AD 276 – 282

After the murder of Florian the senate found itself with no other alternative than to recognize Probus in AD 276.

Though matters should not be easy for the new emperor. the Persian king Sapor had died and the campaign against the Persians was abandoned. If the Goths were quieted, the Germans along the Rhine and the Raetian were growing increasingly active.

Probus, a most distinguished soldier, spent the six years of his reign in vigorous campaigns carried far across the Rhine, enlisting from the barbarians themselves large bodies of auxiliary troops in the service of Rome.

But no series of successes could disguise the fundamental dangers of the situation. While the emperor was constantly personally engaged on campaigns on one frontier, he could not give his attention to other regions of the great empire.

In the east the commander Saturninus was forced into revolt by his own troops. It collapsed before the advance of the imperial forces, as did one or two others still more futile.

The trouble was that such risings were possible even when the emperor was a soldier and statesman as able as Probus.

Still more worrying was that a leader so applauded by soldiers and civilians should suddenly be slain in a mutiny led by the praetorian prefect Carus (AD 282).

Marcus Aurelius Numerius Carus – “Carus”

Reign: AD 282 – 283

Carus, though advanced in years, was an able and experienced soldier. Leaving his elder son Carinus to rule the west, he himself too up the project of the Persian war. On the way eastward, marching through Illyricum, he inflicted a heavy defeat on a horde of Sarmatians, continued during the winter his advance through Thrace and Asia Minor (Turkey), and in AD 283 conducted a triumphant campaign in Mesopotamia and even beyond the Tigris.

Though he soon after met his death in mysterious circumstances, reports saying his tent was struck by lighting during a storm.

Marcus Aurelius Carinus – “Carinus”

Reign: AD 283 – 285

Marcus Aurelius Numerius Numerianus – “Numerian”

Reign: AD 283 – 284

At Carus’ death, rule of the empire fell to his two sons, Carinus and Numerian.

The troops compelled Numerian to abandon the Persian expedition on which he had accompanied his father. He was credited with both character and ability, but his health had broken down under the hardships of the Persian campaign. Though he accompanied his army in its withdrawal westwards he was constantly confined to a sick-bed, where he was rarely seen by anyone else but Arrius Aper, the praetorian prefect. All state business passed through Aper’s hands, so too all communication with the outside world.

At length the general suspicion became intolerable. Soldiers forced their way to their emperor, and found not a sick man, but a corpse.

Aper was then led in chains before a new emperor Diocletian, who had been elected the new ruler from his post of commander of the imperial bodyguard, who executed Aper by his own sword.

A few months later the tyrannical Carinus was slain at the very point of victory in battle over Diocletian, by the dagger of one of his own officer’s whose wife he had seduced.

Partial Recovery

Diocletian splits the empire

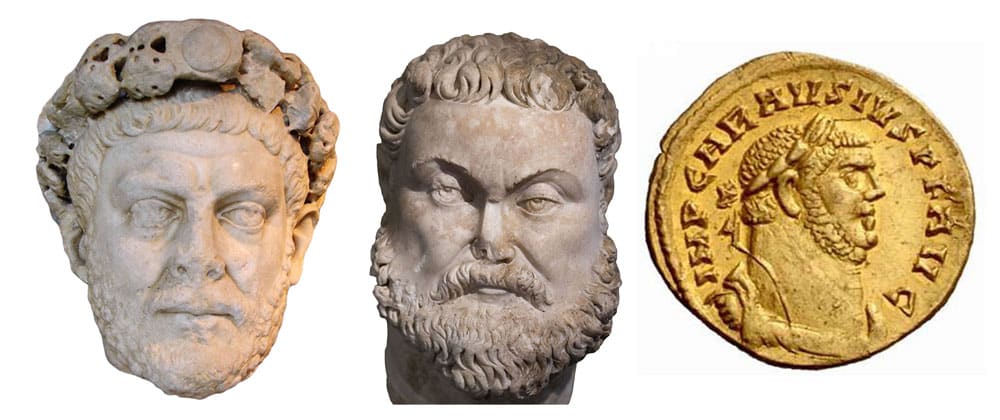

Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus – “Diocletian”

Reign: AD 284 – 311

Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maximianus – “Maximian”

Reign: AD 286 – 310

Mausaeus Carausius – “Carausius”

Reign: AD 286 – 293

One aspect of the problem was not so much that the empire was falling apart, but that it had always consisted of two parts.

Much of the region which comprised Macedonia and Cyrenaica and the lands to the east was Greek, or had been Hellenized before being occupied by Rome. The western part of the empire had received from Rome its first taste of a common culture and language overlaid on a society which was largely Celtic in origin.

Diocletian was an organizer. In AD 286 he split the empire into east and west, and appointed a Dalmatian colleague, Maximian (d. AD 305), to rule the west and Africa. A further division of responsibilities followed in AD 292. Diocletian and Maximian remained senior emperors, with the title of Augustus, but Galerius, Diocletian’s son-in-law, and Constantius (surnamed Chlorus – ‘the pale’) were made deputy emperors with the title of Caesar. Galerius was given authority over the Danube provinces and Dalmatia, while Constantius took over Britain, Gaul and Spain. Significantly, Diocletian retained all his eastern provinces and set up his regional headquarters at Nicomedia in Bithynia, where he held court with all the outward show of an eastern potentate, complete with regal trappings and elaborate ceremonial.

The establishment of an imperial executive team had less to do with delegation that with the need to exercise closer supervision over all parts of the empire, and thus to lessen the chances of rebellion. There had already been trouble in the north, where in AD 286 the commander of the combined naval and military forces based at Boulogne, Aurelius Carausius, to avoid execution for embezzling stolen property, proclaimed himself emperor of Britain and even issued his own coins.

Diocletian ruled for twenty one years until, on 1 May AD 305, he took the unprecedented step of announcing from Nicomedia that he had abdicated, and offered Maximian no choice but to do the same. While his reign had been outwardly peaceful, the years of turmoil had left their mark on the administration of the empire and on its financial situation. Diocletian reorganized the provinces and Italy into 116 divisions, each governed by a rector or praeses, which were then grouped into twelve dioceses under a vicariusresponsible to the appropriate emperor. He strengthened the army (while at the same time purging it of Christians), and introduced new policies for the supply of arms and provisions.

Diocletian’s monetary reforms were equally wide-ranging, but though the new tax system he introduced was workable, if not always equitable, his bill in AD 301 to curb inflation by establishing maximum prices, wages, and freight charges fell into disuse, its effect having been that goods simply disappeared from the market.

Its interest today lies in its comparisons, even though or because these are much as one would expect. Ordinary wine was twice the price of beer, while named vintages were almost four times as much as the ordinary wine. Pork mince cost half as much again as beef mince, and about the same as prime sea fish. River fish were cheaper. A pint of fresh quality olive oil was more expensive that the same amount of vintage wine; there was cheaper oil as well. A carpenter could expect twice the wages of a farm labourer or a sewer cleaner, all with meals included. A teacher of shorthand or arithmetic might earn half as much again per pupil as a primary-school teacher; grammar teachers, and teachers of rhetoric five times as much. Baths’ barbers were all paid the same rate per customer.

Diocletian died in his retirement palace in his native Dalmatia in AD 311, having spent his retirement gardening and studying philosophy, refusing to play any further part in the government of the empire, which immediately after his departure began to founder.

Thre was however a curious episode during Diocletian’s reign which took place in the west of the empire. The western Augustus Maximian had hardly taken office, and proven his authority by crushing an insurrection in Gaul, when Britain declared its independence. For seven years the two Augusti found themselves compelled to recognize a third emperor in the person of Mausaeus Carausius, previously commander of the North Sea Fleet.

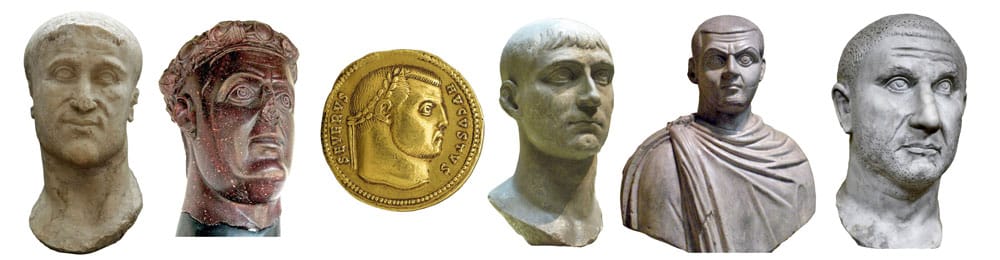

Flavius Julius Constantius – “Constantius Chlorus”

Reign: AD 305 – 306

Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus – “Galerius”

Reign: AD 305 – 311

Flavius Valerius Severus – “Severus II”

Reign: AD 306 – 307

Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maxentius – “Maxentius”

Reign: AD 306 – 312

Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximinus – “Maximinus Daza”

Reign: AD 310 – 313

Valerius Licinius Licinianus – “Licinius”

Reign: AD 308 – 325

When he retired, Diocletian had promoted Galerius and Constantius to the posts of Augustus, and appointed two new Caeasars. The troubles broke out when Constantius died in York in AD 306, and his troops proclaimed his son Constantine as their leader.

Encouraged by this development, Maxentius, son of Maximian, had himself set up as emperor and took control of Italy and Africa, whereupon his father came out of involuntary retirement and insisted on having back his former imperial command.

The situation degenerated into chaos. At one point in AD 308 there seem to have been six men styling themselves Augustus, whereas Diocletian’s system allowed for only two. Galerius died in AD 311, having on his deathbed revoked Diocletian’s anti-Christian edicts. Matters were not fully resolved until AD 324, when Constantine defeated and executed his last surviving rival. The empire once again had a single ruler, and against all the odds he lasted for some years.

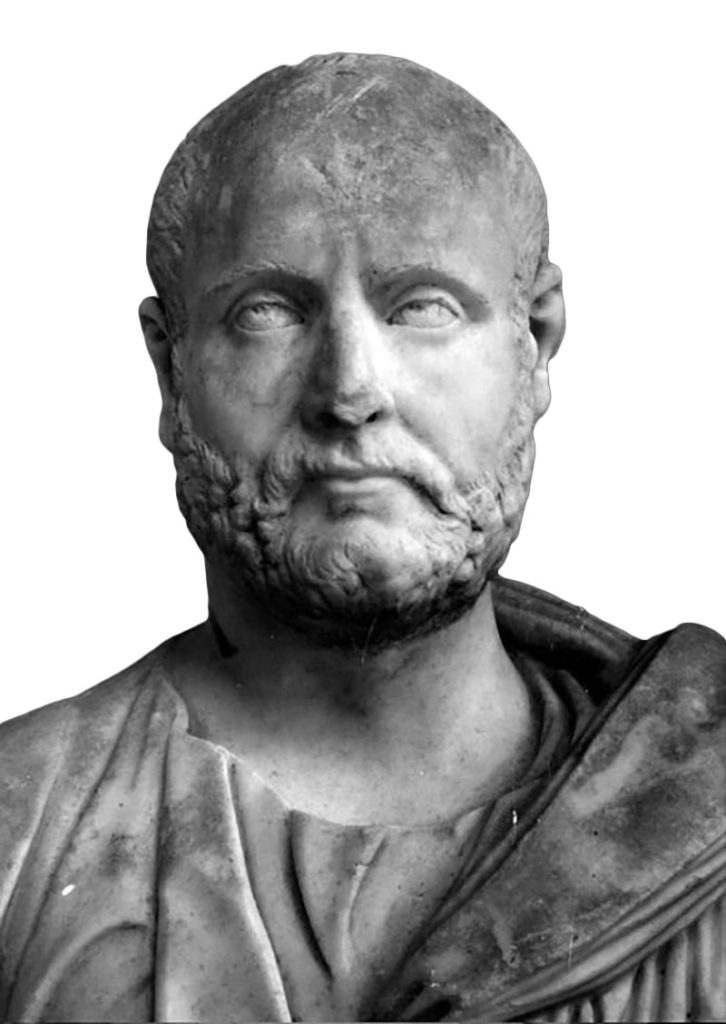

Flavius Valerius Constantinus – “Constantine the Great”

Reign: AD 307 – 337

Constantine was born in Naissus in Upper Moesia in about AD 290, his father subsequently being forced to divorce his mother (a former barmaid) and marry Maximian’s daughter. His appellation ‘the Great’ is justified on two counts. Under Diocletian especially, the Christians had suffered a terrible time. In AD 313, while the struggle for imperial power was at its height, Constantine initiated the edict of Milan – Milan, not Rome, was now the administrative centre of the government of Italy – which gave Christians (and others) freedom of worship and exemption from any religious ceremonial. It is said that before the battle of the Milvian Bridge in AD 312, at which he enticed Maxentius to abandon his safe position behind the Aurelian Wall and then drove most of his army into the Tiber, Constantine had dreamed of the sign of Christ. Thereafter he was not actually baptized until just before his death in AD 337, he regarded himself as a man of the god of the Christians, and can therefore claim to be the first Christian emperor or king. In AD 325 he assembled at Nicaea in Bithynia 318 bishops, each elected by his community, to debate and affirm some priciples of their faith. The result, known as the Nicene Creed, is now part of the Roman Catholic mass and the Anglican churches’ service of communion. And, in AD 330, he established the seat of government of the Roman empire in a town known as Byzantium, which he renamed Constantinopolis (city of Constantine), thus ensuring that a Roman (but Hellenized and predominantly Christian) empire would survive the inevitable loss of its western part. Its capital stood, until the middle of the fifteenth century, as a barrier between the forces of the east and the as yet ill-organized tribes and peoples of Europe, each struggling to find a permanent identity and culture.

To the Jews Constantine was ambivalent: while the Edict of Milan is also known as the Edict of Toleration, Judaism was seen as a rival to Christianity, and among other measures he forbade the conversion of pagans to its practices. In time he became even more uncompromising towards the pagans themselves, enacting a law against divination and finally banning sacrifices. He also destroyed temples and confiscated temple lands and treasures, which gave him much needed funds to fuel his personal extravagances. His reign constituted, however, a series of field days for architects, whom he encouraged to celebrate the religious revolution by reinventing the basilica as a dramatic ecclesiastical edifice.

A general of considerable dynamism, he developed Diocletian’s reforms, and completed the division of the military into two arms: frontier forces and permanent reserves, who could be sent anywhere at short notice. He changed the system of command so that normally the posts of civil governor and military commander were separate. He disbanded the imperial guard, and established a chief of staff to assume control of all military operations and army discipline; the praetorian prefects (commanders of the imperial guard), became appeal judges and chief ministers of finance.

Constantine the Great died 22 May AD 337.

The Decline Chronology

- AD 193-194 Second crisis of the Empire: second year of four emperors, Pertinax, Clodius Albinus, Pescennius Niger, Septimius Severus

- 193-211 Septimius Severus emperor, initiating Severan dynasty

- 194 Severus recognizes Albinus as Caesar but marches against Pescennius. Defeat and death of Pescennius. His followers hold out for two years in Byzantium.

- 195-196 Parthian campaign

- 197 Contest of Severus and Albinus. Death of Albinus at Battle of Lugdunum. Severus sole emperor

- 198 Severus organizes Praetorian Guard under his own command

- 199 The province of Mesopotamia is brought back into the Empire

- 199-200 Septimius Severus in Egypt

- 204 Secular Games (Ludi saeculares) celebrated throughout the Empire

- 206-207 Septimius Severus in Africa

- 208-211 Septimius Severus heads campaign in Britain and dies there

- 211-217 Caracalla emperor

- 212 The Constitutio Antoniniana, issued by Caracalla, confers citizenship on all free men in the Empire

- 216 War again breaks out in Parthia

- 217-218 Macrinus and his ten-year-old son Diadumenianus co-emperors after murder of Caracalla

- 218-222 Elagabalus emperor, reestablishes Severan rule

- 222-235 Alexander Severus emperor

- 224-241 Artaxerxes I reigns over the new Persian empire of the Sassanids (or Sasanians)

- 230-232 Campaign against the Sassanids

- 235-238 Gordianus I and Gordianus II assume emperorship of North Africa

- 238-244 Gordianus III emperor

- 241-271 Sapor I, King of Persia

- 242-243 Victorious campaigns against the Persians; battles of Resenae, Carrhae, and Nisibis

- 244-249 Philippus Arabs emperor and his son co-regent 247-249

- 248 Celebration of millenium of Rome

- 248-251 Decius emperor

- 250 Persecution of Christians

- 251 Decius and his son Herennius Etruscus fall in battle in Abrittus against Goths

- 251-153 Treborianus Gallus emperor

- 253 June-September, Aemilianus emperor

- 253-260 Valerian and his son Gallienus co-emperors, while Valerian campaigns in the East and Gallienus governs the West of the Empire

- 253 Persian War flares up again, Antioch lost to Persia

- 254-262 Revolts of Bagaudae, insurgent peasants, in Gaul and Spain

- 257-260 Persecution of Christian by Valerian

- 260 Valerian taken prisoner by Persians at Edesa

- 260-268 Gallienus sole emperor

- 260 Gallienus extends tolerance to Christians

- 260-272 Queen Zenobia of Palmyra seizes large areas of Asia Minor, Syria, and Egypt and sets up an independant empire until defeated and taken prisoner by Aurelian

- 261-274 Separatist empire set up in Gaul by Postumus (261-268) and Tetricus (270-274)

- 268-270 Claudius II Gothicus emperor

- 270-275 Aurelian emperor

- 276-282 Probus emperor

- 282-283 Carus emperor

- 282-285 Carinus at first co-emperor with Carus and then sole emperor

- 283 Persian campaign of Carus

- 284-305 Diocletian and Maximian co-emperors

- 293 Diocletian creates tetrarchy with himself and Maximian as co-Augusti in the East and West, and Galerius and Constantius Chlorus as co-Caesars

- 297 The Empire is divided administratively into twelve dioceses, each ruled by a vicarius

- 301 The Edict of Maximum Prices imposed throughout the Empire

- 303 Diocletian persecutes the Christians

- 305 Diocletian abdicates and forces Maximian to do likewise. Galerius and Constantius Chlorus co-Augusti

- 306 Constantine declared co-Augustus after death of his father Constantius Chlorus, but Galerius recognizes the Illyrian Severus in that rank and confers the title of Caesar on Constantine

- 306 Maxentius, son of Maximian, hailed as legitimate successor by the Praetorian Guard and the city of Rome; heads revolt against Constantine. His father comes out of retirement to profit from the situation, first on one side, then on the other

- 308 At an imperial conference of Diocletian, Galerius and Maximian at Carnuntum Licinius is declared Augustus of teh West, setting off an armed conflict between all rival contenders

- 310 Maximius Daia, nephew of Galerius, assumes on his own initiative the title of Augustus

- 311 An edict of tolerance for Christians issued by Galerius shortly before his death

- 312 Constantine’s victory over Maxentius in battle at the Milvian Bridge puts Rome in his hands

- 313 Victory of Licinius over Maximinus Daia at the Hellespont is followed by reconciliation of the two victors

- 313 The co-emperors issue the Edict of Milan ending persecution of Christians

- 314 Armed conflict breaks out between the co-emperors: truces, claims, counterclaims, and wars follow for ten years with Constantine increasingly victorious

- 324 Constantine sole emperor after final defeat, abdication, and execution of Licinius

- 325 The Council of Nicaea formulates Nicene Creed and makes Christianity the religion of the Empire

- 326 Constantine chooses Byzantium as the new capital of the Empire and renames it Constantinopolis

- AD 337 May 22, death of Constantine the Great

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.