In 357 AD, a notable event unfolded under the Roman Emperor Constantius II, as an ancient Egyptian obelisk was transported from Egypt to Rome. Crafted from the monumental stones of Egypt’s grand temple, this obelisk made its way across the Mediterranean Sea on a specialized barge. Upon reaching Rome, it was maneuvered through the city on a wooden cradle and erected by the immense efforts of thousands of men. Roman residents were not only amazed by its sheer size and weight but also by the mysterious hieroglyphs that adorned its surface, though these symbols remained undecipherable to them.

The fascination of the Romans, much like the Greeks before them, extended beyond the physical presence of such artifacts to the broader allure of Egyptian culture. Ancient Egypt, with its rich history and abundance of monumental structures, intrigued and mystified the Greco-Roman world. This allure was often tempered by misunderstandings and miscalculations about Egypt’s past, demonstrating the limitations in historical comprehension and the influence of Greek and Roman perspectives on their interpretations of Egyptian history.

Key Takeaways

- The obelisk in Rome symbolized Egypt’s captivating allure.

- The Greeks and Romans marveled at and misunderstood Egypt’s history.

- Cultural transmission gaps shaped historical perceptions.

The Obelisk’s Path to Rome

In 357 AD, Emperor Constantius II decided to move an Egyptian obelisk from a grand temple to Rome. It was a challenging task that involved transporting the obelisk across the Mediterranean Sea on a specially built barge. Upon reaching the shores of Italy, it was floated up the Tiber River. The city streets of Rome then witnessed the enormous structure being transported on a wooden cradle.

Once in Rome, a tremendous effort was required to set the obelisk in place within the Circus Maximus. Thousands of men worked vigorously, using capstones to raise the massive stone onto its new foundation. The obelisk’s impressive height of 105 feet and weight of over 900,000 pounds amazed the crowds that gathered. Onlookers were deeply intrigued by the carvings on its sides. These mysterious hieroglyphs were out of the realm of understanding for the Romans of that time.

The obelisk’s inscriptions told stories of a king named Ramesses, yet no one could ascertain his exact identity or reign. The Romans, much like the Greeks, had limited awareness of ancient historical timelines. Though they had notions about their origins, such as Rome’s founding and the Trojan War, the deeper past remained enigmatic to them.

Egypt held a special place in the imagination of the Greco-Roman world. Its ancient monuments, gods, and sheer cultural depth set it apart. Even with many Egyptians speaking Greek due to centuries of Greek influence and eventual Roman control, understanding the full historical context of these wonders remained elusive. While Egypt was a core part of the classical world, its mysteries continued to captivate the imaginations of those from afar.

Roman and Greek Viewpoints on History

Age Estimations of Ancient Times

The Romans and Greeks had challenges with exact timelines in history. For example, the Romans could not read the hieroglyphs on an Egyptian obelisk they brought to Rome, so they couldn’t understand its true background. Myths filled these gaps in knowledge, and Greeks estimated historical events. They thought Rome was founded around 1100 years before their time, and the Trojan War happened more than 400 years before Rome. However, they had little information about the periods before these times.

Tales and Beliefs of Ancient Ages

The Greeks created stories to make sense of the ruins they discovered. They connected ancient structures to heroes and rulers from legends, such as linking massive stone walls to mythical giant builders. Sometimes old burial sites found with artifacts were assumed to belong to legendary figures, like the hero Theseus or the Roman king Numa Pompilius. Some findings, like cryptic bronze tablets, left experts puzzled due to the lack of understanding of ancient symbols.

Findings and Understanding of Historical Artifacts

Throughout time, the Greeks and Romans struggled to identify old objects. A prominent issue was the misunderstanding of when significant monuments like the pyramids were built. Some speculation leaned towards excessively old or incorrect dates due to flawed information from historical accounts like those of Herodotus, who reached inaccurate conclusions. Despite Egypt being an integral part of the classical world, its culture remained mysterious to many Greeks and Romans, resulting in numerous historical errors.

Encounters with Egypt’s Historic Legacy

Greek Influence and Alexander’s Victory

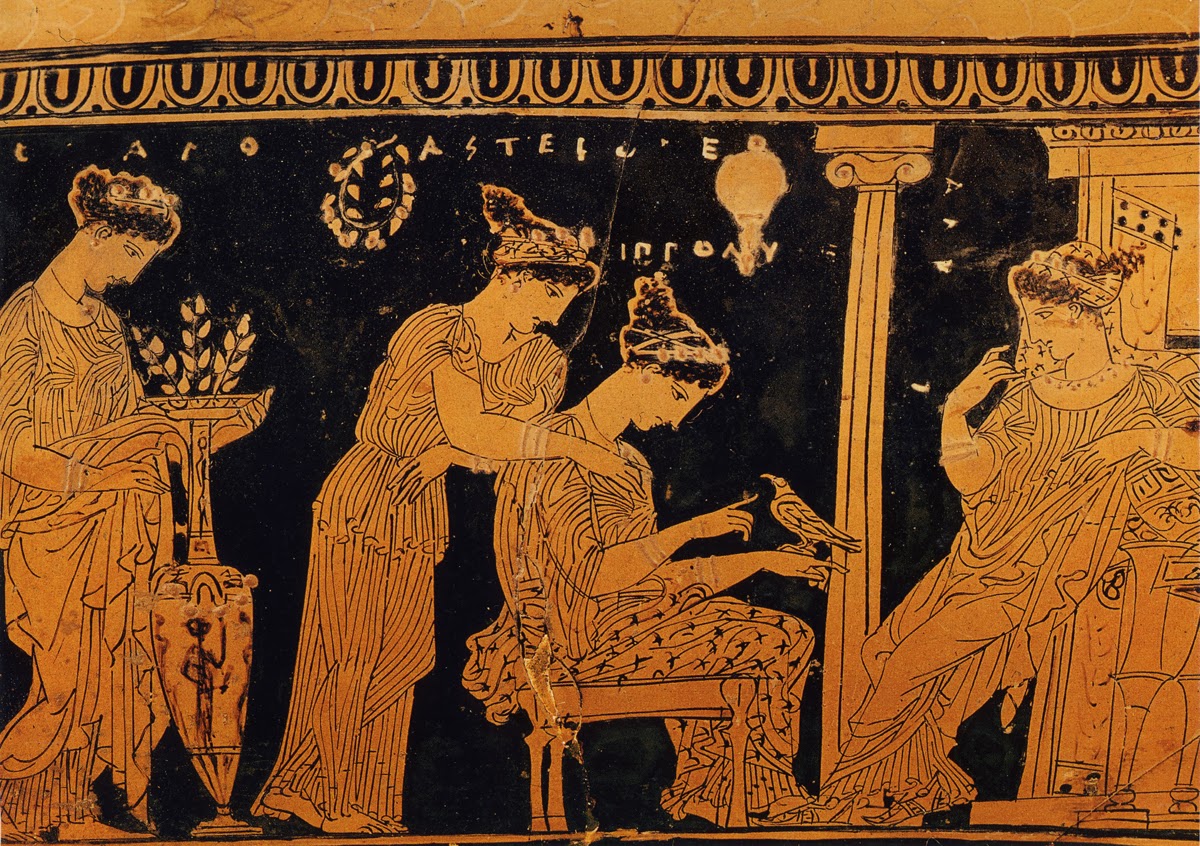

Greek interest in Egypt began in the 7th century BC when traders and soldiers ventured along the Nile. This led to a significant era of Greek control after Alexander the Great conquered Egypt. For three centuries, Greek language and customs took hold, with Greek becoming a secondary language in the region.

Egypt as a Province during Roman and Greek Eras

Following the annexation by Augustus, Egypt became a Roman province for nearly 700 years. Despite its integration into the Greco-Roman world, Egypt retained an exotic allure due to its unique gods, rich material history, and prosperity. Roman elites were particularly fascinated, often building monuments inspired by Egypt and depicting Egyptian themes in their villas. The mystique of Egypt captured the interest of many, making it a land of wonders in Roman eyes.

The Enigma of Egypt: Viewed by Ancient Greece and Rome

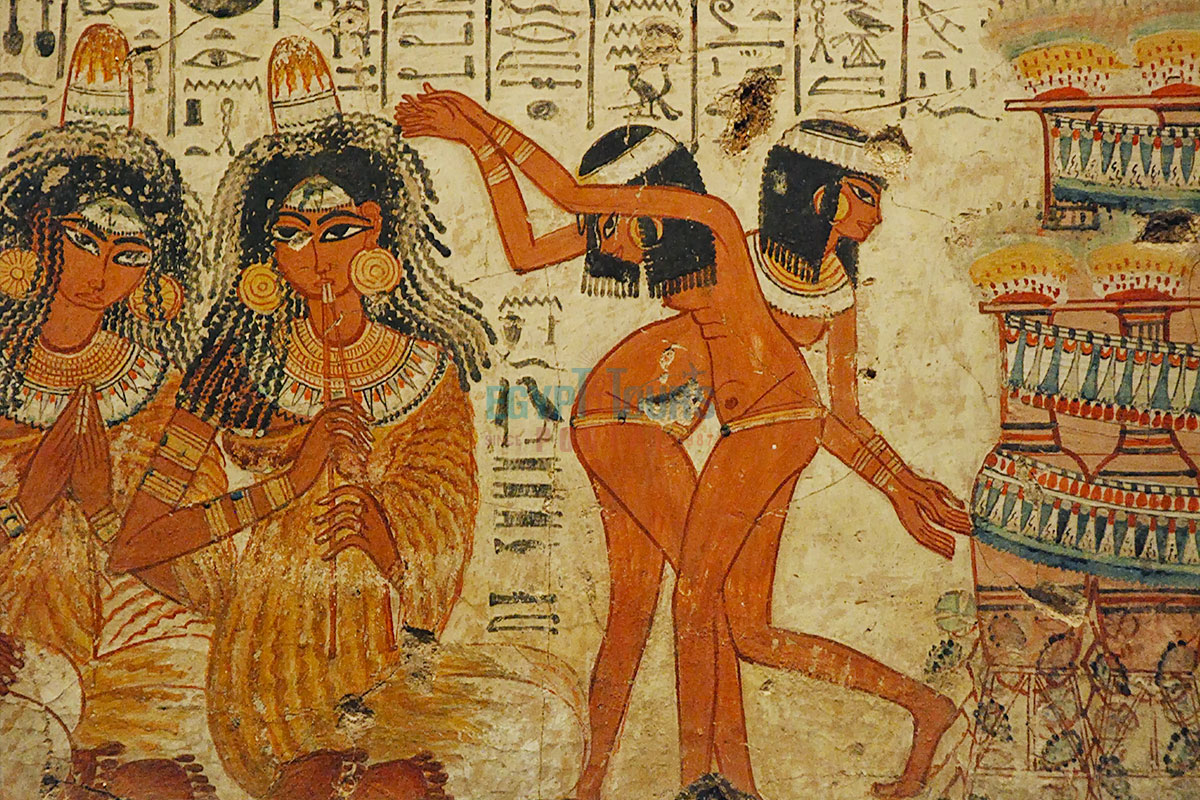

Views on Egyptian Deities and Society

In ancient times, both Greeks and Romans held Egypt in high regard, fascinated by its unique culture and history. They marveled at the pantheon of Egyptian gods, finding them both strange and captivating. Gods with animal heads, a rarity in Greco-Roman mythology, were often subjects of curiosity and, at times, ridicule. Beyond the deities, Egyptians themselves were often seen through a lens of mystery. They were sometimes stereotyped as mystics or even deceivers. Despite these stereotypes, many people from Greece and Rome found Egyptian culture endlessly fascinating, considering the land to be filled with marvels.

Egyptian Allure Amongst the Aristocracy

The Roman elite, particularly, developed a deep interest in the artifacts and architectural wonders of Egypt. Obelisks began appearing in Rome, showcasing this fascination with Egyptian history. These towering structures, along with vibrant Nile scenes painted in villas and pyramid tombs constructed by the affluent, highlighted a cultural blend. Roman tourists, captivated by the grandeur of the pyramids, would even pay locals to guide them in scaling these monumental structures. These structures were considered among the world’s greatest wonders, drawing admiration from visitors all over. Although not always accurate in their historical understanding, the Greco-Roman elite maintained a profound appreciation for Egypt’s ancient and intriguing past.

Tangible Signs of Affluence and Awe

How the Greco-Roman Aristocracy Showed off Their Wealth

The elites of the Greco-Roman world had a fascination with Egyptian culture and its material symbols of power. An example of this was when Emperor Constantius II decided to transport an Egyptian obelisk to Rome in 357 AD. The immense stone was carefully shipped across the Mediterranean on a specially built barge and then raised with great effort in the Circus Maximus. This task involved thousands of men working together to hoist the monumental object, which stood 105 feet tall and weighed more than 900,000 pounds. Although the hieroglyphs covering the obelisk were unreadable to the Romans, the grandeur of the monument itself was a testament to their profound admiration for Egypt’s ancient wonders.

Table: Dimensions of Constantius II’s Obelisk

| Attribute | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Height | 105 feet |

| Weight | Over 900,000 pounds |

The Misunderstood Timelines of the Giza Pyramids

The pyramids at Giza represented marvels that captivated the imagination of the ancient world. Regarded by the Romans as one of Egypt’s most impressive achievements, these structures were considered wonders of the world. Tourists of the time were known to pay locals for the chance to climb the mighty pyramid walls, even leaving graffiti behind as signs of their visit.

The actual age of the pyramids, constructed during the 26th century BC, was a topic often misjudged by classical historians. Herodotus, renowned for his histories, believed these pyramids were built shortly after the Trojan War, around 1200 BC, which was a significant underestimation. Other sources attributed the construction to mythical figures, further distorting historical accuracy. These misconceptions stemmed from a lack of understanding of hieroglyphs, as only a dwindling number of Egyptian priests could still read them. Despite a more accurate account by a learned Egyptian named Manetho, Greek and Roman scholars preferred to rely on their traditional texts and perceptions, which often led to these historical inaccuracies.

The Clash of Ancient Timelines

Herodotus and Diodorus on Egyptian Rulers

Herodotus, a well-known Greek historian, believed the first pharaohs ruled around 15,000 BC. His accounts have been influential, yet his dates are widely considered to be inaccurate. Diodorus, writing approximately four centuries after Herodotus, suggested the Egyptian monarchy began around 23,000 BC. Both guesses contrast with modern understanding, which places the formation of the Egyptian kingdom shortly before 3,000 BC.

The pyramids at Giza present another point of contention. Herodotus thought the great pyramid’s pharaoh ruled two generations after the Trojan War, estimating around 1,200 BC. Diodorus, however, dated this king to the ninth generation post-war, placing it in the 10th century BC.

Misinterpreting Monuments and Dating Errors

The task of dating ancient monuments like Egypt’s pyramids often led to significant errors by Greek and Roman historians. For example, several writers proposed recent construction dates for structures that are, in fact, much older. The pyramid of Mankura, for instance, was incorrectly attributed by tradition to a Greek slave girl turned courtesan in the 6th century BC, rather than its true 3rd millennium BC origins.

This confusion points to a larger pattern of mistakes in understanding Egypt’s past. While some Egyptians could read Greek, hieroglyphics remained largely unreadable to all but a dwindling number of priests. Though an Egyptian named Menetho accurately recorded early Egyptian history around the 3rd century BC, his work was not widely considered until much later. Instead, Greeks and Romans often relied on Herodotus’s inaccurate accounts, preferring familiar narratives over precise interpretations.

How Culture Stops Being Passed Down

Losing the Art of Reading Ancient Scripts

In 357, an emperor moved a large Egyptian obelisk to Rome. Its sides were covered in symbols that nobody in Rome could understand. These symbols told stories of a king named Remestes, but no one knew who he was. At this time, history was a bit hazy, and Rome’s founding and events like the Trojan War were their main reference points. Greek stories filled the gaps for events that happened before these.

Egypt was viewed as an interesting yet exotic place. It had been a part of the Greek and Roman worlds for a long time, but their language and culture made it different. Egyptian culture was known for its fascinating and mysterious nature. Many Greeks and Romans were curious about it, but they often misunderstood its long history.

Menetho’s Lost Histories

In the 3rd century BC, an Egyptian historian named Menetho wrote a history in Greek. He accurately placed the pyramids in the earlier days of Egypt. Despite this, Greeks and Romans preferred other sources. Herodotus, for instance, was a favorite due to his exciting tales, even though his timeline was not accurate.

Their preference meant many Egyptians’ records and Menetho’s work went unnoticed. In a society where most Egyptians could speak Greek but few could read hieroglyphs, important knowledge was ignored. This shows how cultural misunderstandings and selective memory affected the preservation and understanding of history.

Shaping Views of History Through Popular Opinions

Overlooking True Histories

In 357 AD, Emperor Constantius II transported a gigantic Egyptian obelisk to Rome and placed it in the Circus Maximus. This obelisk amazed the people of Rome not only because of its height and weight but also due to the mysterious hieroglyphs no one could understand. The inscriptions praised King Remestes, yet at that time, neither his identity nor his era were known to the Romans. Their historical perspective was shaped more by myths and legendary tales passed down from Greek influences.

The Romans believed their city was founded over a millennium earlier, and they had a rough timeline of events like the Trojan War. However, anything that pre-dated these known periods was mostly unclear. They mainly relied on Greek mythology and their interpretations of classical stories to fill the vast gaps in time. These stories included tales of the Mycenaeans and others, often leading to misinterpretation or fanciful connections with what they found—like attributing ruins to mythical figures such as Theseus.

Cultural Perspectives Favor Certain Stories

The classical civilizations, both Greek and Roman, had a deep fascination with Egypt, seeing it as an enigmatic land full of wealth and ancient wonders. This interest, reflected in architectural features like obelisks and pyramid-shaped tombs, was mostly seen through the lenses of Greek and Roman cultural narratives. While some mocked Egyptian traditions for their perceived oddities, many admired the country’s mysteries and its grand structures, especially the pyramids.

Despite their interest, Greeks and Romans held incorrect beliefs about key Egyptian historical details. They believed the pyramids were built much later than they actually were. While some early historians like Herodotus and Diodorus offered estimates that ranged wildly from the actual construction date, their accounts remained favored over more accurate Egyptian historical treatises like those of Manetho, a historian whose works were largely ignored until much later. The preference for familiar, classic tales and cultural interpretations shaped how these societies perceived Egypt and its rich history.

Investigating Toldenstone’s Material

In 357, Emperor Constantius II had an impressive task. He transported an enormous obelisk from Egypt’s greatest temple to the Circus Maximus in Rome. Moving this giant stone required a specially built barge to travel across the Mediterranean Sea and thousands of men to raise it onto its new base. This obelisk stood 105 feet tall and weighed over 900,000 pounds, with mysterious hieroglyphs that no one in Rome could decipher. These inscriptions spoke about a King named Remestes, but even his story was lost over time.

The Romans, much like the Greeks, had a limited grasp on historical timelines. They tracked their founding to about 11 centuries before the obelisk’s erection and believed the Trojan War to have occurred centuries earlier. However, their understanding of the events that predated these occurrences was influenced heavily by Greek myths and traditions. For instance, the ruins around Greece became linked with tales from the “Iliad” or were thought to have been built by mythological creatures like Cyclopes.

Greek and Roman scholars occasionally relied on interpretations of ancient sites and artifacts, but sometimes, these findings remained enigmatic. For example, when a Spartan king unearthed a bronze tablet adorned with cryptic symbols believed to be linked to Hercules, Greek scholars couldn’t decipher it. As a result, they sent it to Egypt, the oldest civilization known to them.

The connection between Greece, Rome, and Egypt dates back to the 7th century BC when Greek traders began exploring Egypt. The conquests of Alexander the Great introduced Greek as a second language in Egypt, and when Rome annexed Egypt, it remained under Roman influence for nearly 700 years. The Greeks and Romans viewed Egypt as a land filled with wonders, creating a blend of admiration for its wealth and a fascination with its deep history, as seen in the Egyptian-inspired art and architecture around Rome.

Despite many stereotypes and misconceptions about Egyptian culture, the Greco-Roman world held Egypt in high regard. Ancient authors often misdated the age of Egyptian monuments like the pyramids. They mistakenly placed the pyramids’ construction many centuries later than they actually happened. This misinterpretation stemmed from a reliance on Greek historical accounts rather than consulting Egyptian records, which accurately dated these monuments to an earlier period.

Appreciation and References

The emperor Constantius II wanted a giant obelisk from Egypt to stand in Rome’s Circus Maximus. This grand piece, over 100 feet tall and weighing hundreds of thousands of pounds, traveled across the Mediterranean on a specially made barge. Once it reached Rome, it was carefully moved through the city and set up with great effort.

Ancient Rome was deeply fascinated by Egypt, which they saw as an exotic land rich in history. Egypt had been a hub of cultural exchange for centuries, its influence stretching from the Greek era through Roman rule. Despite their great curiosity, both Greeks and Romans struggled to fully understand Egypt’s past, largely because they couldn’t read the hieroglyphs that covered Egypt’s many monuments.

Misinterpretations were common. For example, Roman and Greek tourists mistakenly dated the construction of Egypt’s famous pyramids. While the actual construction dates back to around the 26th century BC, many believed they were built much later. This confusion showed how cultural perspectives influenced their understanding. Although an Egyptian historian, Manetho, recorded accurate accounts, his work was less known among the Greeks and Romans, who favored writings by Herodotus.

Obelisks, pyramids, and other marvels became symbols of Egypt’s enigmatic allure. Their significance, embedded in stories and ruins, continues to captivate modern audiences, reflecting the timeless curiosity about the ancient world.