Life: 63 BC – 14 AD

- Name: Gaius Julius Octavius

- Born on 23 September 63 BC in Rome.

- Son of Gaius Octavius and Aita, niece of Julius Caesar, who adopted him as his heir.

- Consul 43, 33, 31-23 BC.

- Effectively became emperor in 27 BC, with extended powers in 23 BC.

- Married (1) Claudia, (2) Scribonia (one daughter; Julia), (3) Drusilia (one son; Tiberius).

- Died at Nola, 19 August AD 14.

- Deified on 17 September AD 14.

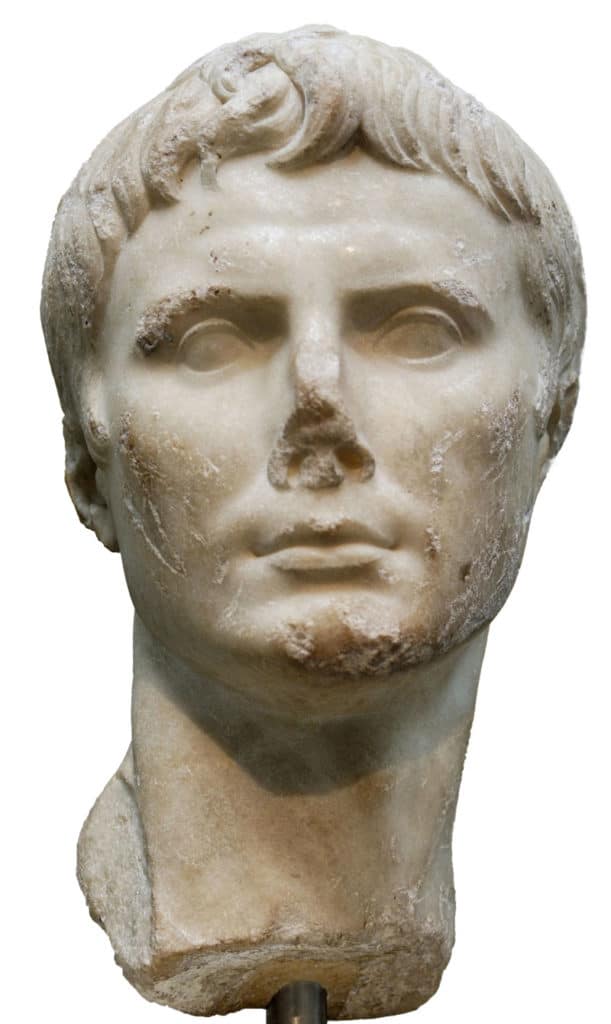

Augustus’s Character and Appearance

The future emperor Augustus was born into an equestrian family as Gaius Octavius in Rome on 23 September 63 BC. His father, Gaius Octavius, was the first in the family to become a senator but died when Octavian was only four. It was his mother who had the more distinguished connection. She was the daughter of Julia, sister to Julius Caesar.

He was of short stature, handsome, and well-proportioned and he possessed that commodity so rare in rulers – grace. Though he suffered from bad teeth and was generally of feeble health. His body was covered in spots and he had many birthmarks scattered over his chest and belly.

As for his character, it is said that he was cruel when young but became mild later on. This, however, might just be because, as his position became more secure, the need for brutality lessened. For he was still prepared to be ruthless when necessary. He was tolerant of criticism, possessed a good sense of humor, and had a particular fondness for playing dice, but often provided his guests with money to place bets.

Although unfaithful to his wife Livia Drusilla, he remained deeply devoted to her. His public moral attitudes were strict (he had been appointed pontifex (priest) at the age of fifteen or sixteen) and he exiled his daughter and his granddaughter, both named Julia, for offending against these principles.

Octavian as Caesar’s Heir

Octavian served under Julius Caesar in the Spanish expedition of 46 BC despite his delicate health. He was to take a senior military command in Caesar’s planned Parthian expedition of 44 BC, although at the time he was only 18 years old.

But Octavian was with his friends Marcus Agrippa and Marcus Salvidienus Rufus in Apollonia in Epirus completing his academic and military studies, when news reached him of Caesar’s assassination.

At once he returned to Rome, learning the way that Caesar had adopted him in his will. No doubt this only increased his desire to avenge Caesar’s murder.

Though when he arrived Octavian found power in the hands of Mark Antony and Aemilius Lepidus. They were urging compromise and amnesty. But Octavian refused to accept this attitude. With his determined stand, he soon succeeded in winning over many of Caesar’s supporters, including some of the legions.

However, he failed to persuade Marc Antony to hand over Caesar’s assets and documents. Therefore Octavian was forced to distribute Caesar’s legacies to the Roman public from whatever funds he was able to raise himself. Such efforts to see Caesar’s will done helped raise Octavian’s standing with the Roman people considerably.

Many of the senators, too, were opposed to Antony. Octavian, appreciated as Antony’s primary rival by then, was granted the status of senator, despite not yet being twenty.

The Triumvirate

During the summer of 44 BC the senate’s leader, Cicero, delivered a series of infamous speeches against Marc Antony which came to be known as the ‘Philippics’. Cicero saw the young Octavian as a useful ally. So, when in November 44 BC Antony left Rome to take command in northern Italy, Octavian was dispatched with the senate’s blessing to make war on Antony. Marc Antony was defeated at Mutina (43 BC) and forced to retreat into Gaul.

But now it showed that Cicero had definitely lost control of the young Octavian. Had the two reigning consuls both been killed in the battle, then in August 43 BC Octavian marched on Rome and forced the senate to accept him as consul. Three months thereafter he met with Antony and Lepidus at Bologna and the three came to an agreement, the Triumvirate. This agreement between Rome’s three most powerful men completely cut off the senate from power (27 November 43 BC).

Cicero was killed in the proscriptions that followed. Brutus and Cassius, Caesar’s chief assassins, were defeated at Philippi in northern Greece.

Octavian and Marc Antony, the winners at Philippi, reached a new agreement in October 40 BC in the Treaty of Brundisium. The Roman empire was to be divided between them, Antony taking the east, and Octavian the west. The third man, Lepidus, was no longer an equal partner. He therefore had to make do with the province of Africa. To further strengthen their agreement, Antony married Octavian’s sister Octavia. But it was not to be long before Antony abandoned her to return to his lover Cleopatra.

Meanwhile, Octavian’s own standing had been heightened by the deification of Julius Caesar in early 42 BC. He was no longer to be addressed as ‘Octavian’ but insisted on being called ‘Caesar’ and he now styled himself as ‘divi filius’ – ‘son of the divine’.

He used the following years to strengthen his hold over the western provinces. Also in this time Marcus Agrippa, Octavian’s most loyal friend, delivered Italy from the menace of the fleet of Sextus Pompeius, a son of Pompey the Great.

As Lepidus fell by the wayside during the conflict with Sextus Pompeius, this left Antony and Octavian rulers of the Roman world. Antony lived openly with Cleopatra, queen of Egypt. Octavian’s apparent modesty and moral strictness contrasted strongly with Antony’s life as an oriental monarch at the lavish Egyptian court. Rome’s sympathies therefore clearly lay with Octavian.

By 32 BC the agreement made at Tarentum (an extension of the Treaty of Brundisium by four years) strictly speaking had run its course and the Triumvirate ceased to be. Octavian tried to maintain the charade that he really wasn’t exercising any powers.

The Civil War

When Antony divorced Octavia, Octavian lashed out by reading out in public Antony’s will, which had quite illegally come into his possession.

This promise not only large inheritances to his children by Cleopatra but also demanded that should he die in Italy, his body should be returned to Cleopatra in Egypt. Antony’s will was the final straw. For in all Rome’s eyes, this could never be the will of a true Roman. The Senate declared war.

At Actium on the west coast of Greece on 2 September 31 BC, the fateful battle took place. Once again it was Agrippa who commanded the forces on behalf of his friend Octavian and won victory.

Both Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide. The vast treasures of Egypt fell to Octavian, and Egypt itself became a new Roman province.

Octavian’s next, highly questionable act wasto put to death Cleopatra’s son Caesarion. Caesarion in fact was the child of Cleopatra and Julius Caesar. Octavian being the adoptive son of Caesar, he in essence ordered the death of his step-brother.

Augustus

Victory of Actium had given Octavian the undivided mastery of the Roman world. But this position had once been held before by Julius Caesar. Octavian was not one to forget what fate had befallen Caesar. In order to prevent a similar demise, he needed to create a new constitution.

Hence on January 27 BC Octavian in the so-called ‘First Settlement’ went through a strangely orchestrated ceremony in which he ‘surrendered’ all his power to the senate – thus restoring the Republic. It was a purely symbolic sacrifice as he received most of the very same power right back again.

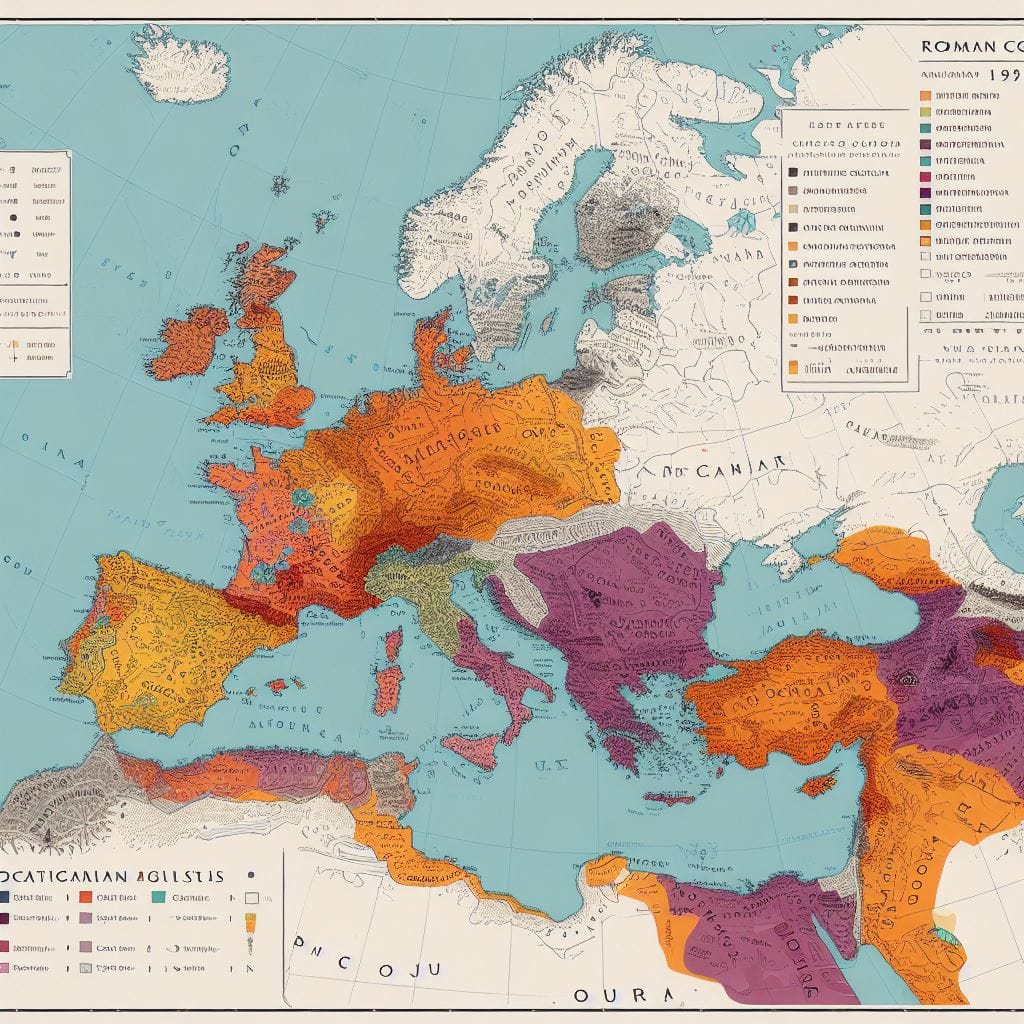

The entire effort was meticulously planned and overseen by his supporters and associates. Octavian received into his personal control, for ten years, the vitally important provinces of Egypt, Cyprus, Spain, Gaul, and Syria. Also, he was continually re-elected as consul from 31 to 23 BC.

Further, he now received the name ‘Augustus’, a slightly archaic term, meaning ‘sacred’ or ‘revered’. Augustus apparently preferred the term ‘princeps’ (first citizen) which he had been granted, though he also kept the title imperator to point out his position as military chief of staff.

Octavian’s great achievement was persuading the senate to accept him as head of the Roman state while leaving the senators room for their political ambitions.

From the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire

Augustus left Rome for Gaul and Spain to put down truculent tribes in the summer of 27 BC and did not return until 24 BC. Then in 23 BC Augustus fell so seriously ill that he himself thought he was dying. This brush with death appeared to have been a further decisive moment in his life. When he recovered, he set about once more to change the Roman constitution.

In the ‘Second Settlement,’ Augustus gave up the consulship and instead was awarded tribunician powers (tribunicia potestas) for life by the senate.

Tribunician powers gave him the right to call the Senate to meetings, to propose legislation in the popular assembly, and to veto any enactments. Also, his command over ‘his’ provinces was renewed.

Then in 19 BC he also was granted not merely the consulship (which lasted for one year) but consular power for life. His power was thereafter unassailable. Augustus held equal power to the most powerful politicians in Rome and yet greater power still in the provinces of the empire.

On the death of Lepidus (12 BC), the failed third Triumvir, who had been shunted aside with the conciliatory position of pontifex maximus, Augustus assumed the highest of all religious positions for himself.

Perhaps the highest point came in 2 BC when the senate granted Augustus a new honor. He was henceforth pater patriae, the father of the country.

Octavian Augustus as the leader of Rome

Augustus was undoubtedly one of the most talented, energetic, and skillful administrators that the world has ever known. The enormously far-reaching work of reorganization and rehabilitation that he undertook in every branch of his vast empire created a new Roman peace with unprecedented prosperity.

Following in the footsteps of Julius Caesar, he won genuine popular support by hosting games, erecting new buildings, and by other measures for the general good. Augustus himself claimed to have restored 82 temples in one year alone. But further, there were grand new buildings like the Theatre of Apollo, the Horologium (a giant sundial), and the great Mausoleum of Augustus.

Augustus’ right-hand man Agrippa, too, embarked on several major building projects. Among these were the Pantheon, later rebuilt by Hadrian. Agrippa also repaired the city’s water system and added two new aqueducts, the Aqua Julia and the Aqua Virgo.

One building though is clearly lacking from Augustus’ reign – a palace. He lived in a spacious house on the Palatine Hill, evidently avoiding any symbols of monarchy. And although he did continue to style himself ‘divi filius’, son of the deified Caesar, he clearly avoided any form of worship to his own person as was the case in the eastern world, where rulers were themselves frequently worshipped as gods.

Most of all, Augustus appeared to appreciate that his personal standing and security benefitted from governing in the public interest.

Military Conquests

Augustus was no great military commander, but he possessed enough common sense to recognize that this was so. And so he relied on Agrippa to do his fighting for him. After Actium, Augustus only once took command of a campaign (the Cantabrian War of 26-25 BC) in Spain. But even there he eventually had to rely on one of his generals to bring the war to a successful conclusion.

Despite his lack of military skill, Augustus achieved vast gains in imperial territory as well as in the standing of Rome.

Most important was no doubt the conquest of Egypt in 30 BC. Then in 20 BC, he recovered the legionary standards captured by the Parthians at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC simply by threatening Parthia with war. Also, he made the Danube the frontier in the east of Europe after his forces fought hard campaigns conquered the Alpine tribes, and occupied the Balkans.

But his attempts at making the river Elbe the empire’s northwestern frontier ended in the Varian disaster and it became clear to everyone that the Rhine was to be the future border.

Under Augustus, the army was thoroughly reorganized strengthened, and posted away from Italy into the provinces. He also remodeled the civil service and substantially rebuilt some parts of Rome, even appointing 3,500 firemen under a chief fire officer.

Troubles With the Succession

No one could ever have foreseen the success of Augustus’ reign. His long life only further created him and his family as the natural rulers in the eyes of the Roman people. However, creating a dynasty proved very difficult for Augustus.

At first, he clearly understood his loyal friend Agrippa to be his obvious successor. And, when he believed himself to lay dying in 23 BC, it was indeed Agrippa he handed his signet ring to. As his marriage to Livia, except for a premature birth, produced no children, his plans of inheritence therefore involved his daughter Julia from his previous marriage to Scribonia.

Had Julia been married to Marcellus in 25 BC (the son of Augustus’ sister Octavia), then Marcellus was also a potential heir. But Marcellus died soon after 23 BC.

So, with Agrippa his only possible successor, Augustus had his friend divorce his existing wife and marry the widowed Julia. Agrippa was 25 years older than his new wife, but their marriage brought forth three sons and two daughters. Augustus adopted the sons Gaius and Lucius as his own.

Then in 12 BC Agrippa died. Augustus realized that should he himself die, the two young boys would be left without a guardian.

Therefore, Augustus turned to his wife Livia’s two adult sons from her previous marriage. He made the elder son, Tiberius, divorce his wife Vipsania marry Julia, and become protector of the young princes.

Tiberius deeply loved his wife Vipsania and strongly resented Augustus’ demands, but the marriage went ahead on 12 February 11 BC.

As both Gaius and Lucius died early in their lives, Augustus was left with only one choice of successor – Tiberius, son of Livia. And so, on 26 June AD 4 he somewhat reluctantly adopted the equally reluctant 44-year-old Tiberius, together with the 15-year-old Agrippa Postumus, the youngest son of Agrippa and Julia.

Postumus though soon turned out to be a violent and thoroughly nasty individual and so was sent into exile only three years later.

During his final years, Augustus withdrew more and more from public life. Intending to travel with Tiberius to Capri, and then on to Beneventum, he left Rome for the last time in AD 14.

He fell ill on the way to Capri and, after four days resting on Capri, when they crossed back to the mainland Augustus at last passed away. He died at Nola on 19 August AD 14, only one month away from his 76th birthday.

The body was taken to Rome and given a stately funeral and his ashes were then placed in his Mausoleum.

People Also Ask:

What is Emperor Augustus famous for?

Emperor Augustus led the transformation of Rome from a republic to an empire.

Who is Augustus to Julius Caesar?

Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus was the great-nephew and adopted son and heir of Julius Caesar.

What caused Augustus downfall?

The Roman emperor Augustus never suffered a downfall. He was one of the very few emperors to die of natural causes and that after an extremely long reign (40 years).

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.