Period: 123 – 23 BC

The story of the late Roman republic is essentially a tragic one.

Yet the various causes for the demise of the republic are far from clear cut. One can not point to one single person or act which led to the fall.

Looking back one feels that most of all the Roman constitution was never designed with the conquest of wealthy overseas territories in mind.

With the addition of ever more provinces, especially that of Asia (Pergamene), the delicately balanced Roman political constitution began to collapse from within.

For individual politicians, especially for those with a talent for military command, the prize of power became ever more extraordinary as the empire expanded.

Meanwhile, on the streets of Rome the will of the Roman electorate was of ever greater consequence, as their favour granted a politician ever greater powers.

In turn the electorate was flagrantly bribed and cajoled by populists and demagogues who knew that, on achieving power, they could recoup any costs simply by exploiting their offices overseas.

Had in the earlier days of Cincinnatus high office been sought for status and fame within Roman society, then the latter days of the Roman republic saw commanders win vast fortunes in loot and governors make millions in perks and bribes in the provinces.

The key to such riches was the Roman electorate and the city of Rome.

Therefore who controlled the Roman mob and who held the pivotal positions of tribunes of the people was now of immense importance.

The fate of the ancient world was now decided in the miniature world of one city. Her town councillors and magistrates suddenly were of importance to Greek trade, Egyptian grain, or wars in Spain.

What had once been a political system developed to deal with a regional city state in central Italy now bore the weight of the world.

The very virtue of Roman unchanging stoicism now became Rome’s undoing. For without change a catastrophe was inevitable. Yet adaptable as the Roman mind was to matters of warfare, it was resistant to any sudden change in political rule.

So, as the Roman elite did, what it was bred to do, as they competed ruthlessly with one another for the highest positions and honours, they unwittingly tore apart the very structure they were sworn to protect.

More so, those who possessed extraordinary talents and succeeded only reaped the suspicion of their contemporaries who at once suspected their seeking the powers of tyranny. Had previously Rome handed extraordinary commands to great talents when a crisis required it, then towards the end of the republic the senate was loath to grant anyone commissions, no matter how urgent the situation became.

Soon it therefore became a contest between those of genius and those of mediocrity, of aspiration and vested interests, between men of action and men of intransigence.

The descent was gradual, unperceivable at times. Its final acts, however, proved truly spectacular. It is little wonder that this period of Roman history has proved a rich source of material for dramatic fiction.

Much more material has survived regarding this period of Roman history. Hence we are provided with much greater insight of the events of this era. Thus, this text can elaborate on the problems in much greater detail.

The Brothers Gracchus

The first fatal steps in the eventual demise of the republic can most likely be traced back to the disgraceful behaviour of Rome in the Spanish wars.

Not merely did the lengthy campaigns lead to an ever greater alienation between the citizens who supplied the soldiery for lengthy campaigns overseas and the leadership back in Rome. – It must be noted that in 151 BC citizens went as far as refusing the call up for another levy to be sent to Spain. So far had the resistance toward serving in Spain grown.

But more so, the scandalous Roman conduct in Spain most likely directly contributed to the eventual break with the nobility by the brothers Gracchus.

For it was at Numantia (153 BC) that a young tribune, Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, staked his reputation on a treaty with the Spaniards in order to save the trapped army of Mancinus from certain destruction.

Once the senate dishonorably revoked this treaty, it not merely betrayed the Numantines, but so too it disgraced Tiberius Gracchus – and so set in motion a dreadful chain reaction which should play itself out over more than a century.

It is true that Scipio Aemilianus did his best to shelter his brother in law from the dishonour of the defeat at Numantia. Tiberius Gracchus could most likely have gone on to enjoy a distinguished senatorial career, following in his father’s footsteps to both the consulship and the censorship.

However, the outright betrayal by the senate evidently had some profound, lasting effect. If we consider the Roman understanding of family honour then it is perhaps not surprising that Tiberius Gracchus took grievance at his treatment.

The faith of the Numantines had been placed in the honour of his word, due to his father’s name. Once the senate revoked the treaty it will therefore have destroyed any honour and respect the name Gracchus commanded in Spain.

Tiberius saw not merely his own person disgraced, but also the memory of his father sullied.

Tiberius Gracchus shocked the Roman system by standing not for a magistracy, but for the office of tribune of the people for 133 BC.

This was a momentous step. An outstanding member of the Roman nobles, who was clearly destined to be consul, instead was taking office as the representative of the ordinary Roman people.

Gracchus was hardly the first man of good family to seek the tribunate, but he was a man of extraordinary high standing, for whom the tribunate was never intended.

The tribunate, however, carried with it the powers of veto and to propose law. Clearly it had never been designed as an office to be held by a political heavyweight such as a Gracchus.

Nonetheless the moment Gracchus stood for the office it was clear that he was seeking to rival the consuls in their power. In doing this he was acting according to the letter of the law, but not in the spirit of the Roman constitution.

This set an ominous precedent that many would follow.

But so too Tiberius Gracchus was set on a collision course with the senate. Had previously other wellborn sons aspired to the tribunate it had been in a spirit of solidarity with the ruling class. Tiberius was to change this. He was looking for a fight.

The Roman senatorial class saw its first member break ranks, albeit that this at first will not have been apparent.

For a candidate to the tribunate Tiberius Gracchus had astounding backers.

He probably had the support of Servius Sulpicius Galba, who’d been consul in 144 BC, and Appius Claudius Pulcher, ex-consul of 143 BC and the leading senator of the day (princeps senatus). Another former consul, M. Fulvius Flaccus, was also at his side. So too he enjoyed the support of the famous jurist P. Mucius Scaevola who was standing for the consulship in that very year. Further supporters were C. Porcius Cato and C. Licinius Crassus. It was a roll call of the great and the good.

More so the program of law he proposed for taking office was impressive. Most of all it hinged on his ideas for land reform.

On traveling to Spain he had observed the decline of farming in Etruria, seeing how the Italian smallholders, whom Rome depended on for her soldiery, were declining in numbers as they succumbed to the competition by the massive farms (latifundiae) of the wealthy, worked by armies of slaves.

Many of these vast farms of the rich were actually situated on public land (ager publicus), which they rented for pitifully small leases from the state, if they paid for it at all.

Gracchus made clear that public land was just that; public property. He was to attempt a redistribution of this land to the poor.

With such proposals popular support came easy. Given Gracchus’ powerful backers victory was a foregone conclusion.

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus was hence elected tribune for the year 133 BC.

Tiberius Gracchus’ Land Reform

The sheer support that Gracchus had from the most powerful of Rome’s politicians demonstrates quite clearly that many saw land reform as overdue. This was not radical or extremist legislation.

Rome’s conquests had handed her vast tracts of land which were owned by the state. Only the wealthy and powerful had the necessary connections to secure the leases necessary to farm these lands.

By the time of Gracchus the rich had come to treat these lands as their own, leaving them in wills and passing them on as dowries.

This was utterly improper. More so it offended an ancient law which had fallen into disuse, the Licinian Rogations (367 BC). It is true that the Licinian laws on land reform never really had great effect, as they were easily circumvented. Nonetheless, they had never been revoked.

This provided Gracchus with a sound precedent in law.

Gracchus now proposed to reinstate the limit whereby no man could own more than 500 iugera of land (300 acres).

To sweeten the pill, he offered that the current holders of public land could keep 300 acres as their undisputed property, including another 150 acres for every child. Any wealthy man with four children would therefore easily stand to keep 1000 acres.

These lands would no longer be public in nature, held by lease, but would be private property.

Details are unclear, but the above suggests that the rich landowners would only be curbed in their holdings of public land. What other lands they already outright owned would have remained untouched. Thus, the old Licinian Law would have been superseded, legitimizing their vast properties. This in turn made the reforms attractive to some rich land owners.

The freed up land in the ager publicus was to be redistributed in plots of 30 acres to family smallholders.

By creating thousands of new landowners, Rome would refresh her stock from whom to recruit for her armies. The plots, once granted, were to be inalienable. This meant they could not be sold or transferred to new owners in any way, other than by inheritance passed from father to son.

It was no doubt a good idea at the time and Gracchus’ proposal seems indeed to have been heartfelt and sincere. But with hindsight it is unclear how these smallholders could have competed for any length of time with the slave run latifundiae of the rich – especially, if they were to be regularly called away on military service.

This said, smallholdings had by no means disappeared by this time and it is possible that Gracchus’ with his contemporary knowledge was indeed correct in his assertions and was laying down a long-term plan to distribute land to the urban poor and provide Rome with recruits into the far future.

But Tiberius Gracchus knew he’d have a fight on his hands. Similar land reform had been proposed some ten years earlier by C. Laelius (ca. 145 BC), who eventually withdrew it in the face of determined opposition.

The main opposition was invariably composed of those who held significant public lands. For those who were to lose the lion share of their public lands and had no great holdings of further private estates, Gracchus’ law could represent a crushing blow.

Chiefest among these opponents was to be Scipio Nasica, ex consul of 138 BC, who held vast amounts of public land.

Tiberius Gracchus’ land reform bill was meticulously drafted. Most likely due to the direct help of P. Mucius Scaevola who had indeed succeeded in gaining the consulship for that same year.

But Gracchus presented the bill directly to the people’s assembly (concilium plebis). He did not submit the law for review to the senate. Again, the latter was not required by law. Yet it was the established practice.

Why Tiberius Gracchus decided to proceed this way is unclear. It is very likely – feeling betrayed by the senate for the Numantia affair – he sought to by-pass them in contempt.

Whatever his reasons may have been, the senate took offence. There can be little doubt that Gracchus had formidable political support. His bill may indeed have been passed by the senate with little amendment, if any. After all, he had no less than the leader of the senate and one of the incumbent consuls on his side. The law seemed designed for the public good and its opponents had only self-interest at heart.

But Rome’s most powerful political body resented that it was not being consulted and sought to block the law’s progress.

To this end the senators secured the services of another tribune, Marcus Octavius.

Octavius now vetoed Gracchus bill.

Tiberius Gracchus use of the tribunate was questionable. But Octavius now used his position to defy the will of the very people he was supposed to represent. For this the office had never been intended. The tribunate was being corrupted into the tool of the senatorial order.

People no doubt expected that Gracchus would either withdraw from his attempt or seek to somehow come to terms with the senate.

Tiberius Gracchus however intended no such thing.

Gracchus is said to have offered Octavius, who it seems had holdings of public land of his own, that he would compensate him personally for any losses he incurred, if only he would let the bill pass. Octavius refused, staying loyal to the senate.

Instead Gracchus now proposed the removal of Marcus Octavius from office, unless the latter was willing to withdraw his veto. Octavius remained defiant and was promptly voted out of office, dragged from the speaker’s podium and replaced with a more agreeable candidate.

Once again no-one knew if this was lawful or not. This was utterly unprecedented.

Gracchus actions were most likely not in breach of Rome’s constitution, though neither were they in the spirit of it.

With Octavius out of the way, the law passed unhindered. A commission was set up, to oversee the distribution of land to the people.

The senate however withheld any moneys that were necessary to help stock the new smallholdings. Without any funds to provide the basic necessities, any plots distributed were bare parcels of land, not viable farms.

Tiberius Gracchus therefore seized on the wealth of the kingdom of Pergamene which in that very year had just been left to the Roman state by the late King Attalus III (133 BC).

He announced a bill whereby some of the money gained from this enormously wealthy new territory would be directed to agrarian commission in order to help set up farms for new settlers.

Once more the legality of all this was murky. The senate enjoyed sovereignty over all issues of overseas matters. Yet where was it explicitly written to be so?

Tiberius Gracchus was bending the rules to the utmost, in utter disregard of the senate and Roman tradition.

So far though he had succeeded. He had both the land and the funds he needed to begin land distribution.

His agrarian commission now went to work, handing out parcels of land.

Yet Gracchus had made powerful enemies. Worse, many of his allies had broken away, once he grabbed the Pergamene moneys in defiance of the senate.

It became clear that once his term of office came to an end, his foes would drag him through the courts, seeking to destroy him.

The only means of protection open to Gracchus was to stand for a new term of tribune, as this would extend his immunity from prosecution.

Roman law dictated that a successful candidate wait another ten years before standing for the same office again. But the law strictly speaking only applied to magistracies (lex villia, 180 BC). The tribunate, however, was technically not a magistracy. Yet tradition dictated that tribunes follow the rule nonetheless.

Once more it is unclear if Tiberius Gracchus was in breach of the law. But yet again it is self-evident that he didn’t follow the spirit of the law.

Gracchus’ chances on winning office for 134 BC did not look good. Many of his rural voters were busy with the harvest. His powerful political allies had abandoned him and he had clearly lost the support of his fellow tribunes.

Had he now simply lost the upcoming election much of what befell Rome in future years might still have been avoided.

Alas, Scipio Nasica, after haranguing the senate in vain to take action, took matters into his own hands and led a mob of supporters and nobles to the Capitol where Gracchus was holding an electoral assembly. Armed with clubs they set upon the meeting and beat Tiberius Gracchus and 300 of his supporters to death.

The rise and fall of Tiberius Gracchus set an awful example.

Not merely had Gracchus undermined the notion of communal spirit in the governing of Rome, but his vicious murder introduced plain brutality as a political tool onto the streets of Rome.

An unholy example had been set by which all involved declared that only victory – by any means – was acceptable. Neither side sought to compromise and neither side sought to adhere to the spirit of the republic. The rules, it appears, could be circumvented ‘for the public good’.

It may be true that Tiberius Gracchus was the instigator of the crisis. But the way in which Scipio Nasica and other forces in the senate responded was beyond the pale. They no doubt share as great a responsibility, if not a greater one, for the terrible legacy this case bestowed on Rome.

Ironically, Gracchus’ land law continued on for years to come. As a result by 125 BC seventy-five thousand citizens were added to the list of those liable for military service, when compared to the census figures of 131 BC. Undeniably, his policy did prove a success.

The Aftermath of Tiberius Gracchus

The death of Tiberius Gracchus was followed by a witch hunt by the senate, in which many of his supporters were sentenced to death.

Tiberius younger brother Gaius was also prosecuted, but easily defended himself and was cleared.

Scipio Nasica meanwhile was posted to the new province of Asia, in order to protect him from the wrath of any Gracchan supporters. (His death soon after nonetheless was deemed suspicious.)

In 131 BC a tribune by name of C. Papirius Carbo proposed both that elections should henceforth be held by secret ballot and to clarify the law that tribunes should be able to stand for successive terms of office.

The former proposal was accepted, but the latter was defeated on the intervention of Scipio Aemilianus who had since returned from Spain. Such was the standing of the great commander that the popular will bent to his.

Though on Scipio’s death (129 BC), another tribune re-introduced the proposal and the measure was accepted. (This inadvertently cleared the way for the emperors who a century later would begin their rule by tribunician powers.)

There is the suspicion that Scipio Aemilianus was in fact murdered by his wife, Sempronia, who was the sister of Tiberius Gracchus.

This suggestion, if true or not, is no doubt connected to Scipio’s refusal to openly condemn the murder of Tiberius Gracchus.

In a strange twist much of the political reform which had made Tiberius Gracchus such a problem was introduced or simply continued after his death.

It appears a peculiar characteristic of Roman politics to seek to win the fight at all costs, yet to concede the point after victory has been achieved.

Prior to his death, however, Scipio Aemilianus sought to address the problem faced by the Italians.

The Gracchan land distribution dealt with all public land. Yet many public lands were used by the Italians, who had either never been removed from them on conquest, or had encroached onto them with the passage of time. Many therefore faced complete ruin, if the agrarian commission handed the land they farmed to new settlers.

Scipio was fully aware of the debt he owed to the Italian allies. His military victories were as much due to them as they were due to the Roman legionaries.

He therefore in 129 BC, shortly before his death, convinced the senate to transfer the power to settle disputes on public land held by non-Romans from the agrarian commission to one of the consuls.

This protected the Italians from mob’s clamour for land. However, it could not prevent the inevitable conflict, as the Italians continued to demand greater rights.

In subsequent years many Italians did begin to drift into Rome, lobbying and agitating for greater entitlements. In 126 BC the tribune Iunius Pennus even passed a law expelling non-citizens from Rome. It is unclear how many of the rich foreign merchants and traders circumvented this law, or to what extent it was ever enforced against them. For it seems clear that the measure was really targeted at evicting the Italian agitators.

But Italian discontent had not gone unnoticed. In 125 BC consul Marcus Fulvius Flaccus proposed to grant them citizenship (or at least full citizenship to the Latins and Latin privileges to all Italians in preparation of eventual full citizenship) .

The opposition to this idea was two-fold. The poor saw any increase of the number of citizens as a lessening of the privilege of citizenship and the senators saw the mass of Italians as a threat to their political standing, as they held no traditions of political patronage over them. Invariably, the measure hence had little hope of success. But to curb any risk of it succeeding, the senate dispatched Flaccus off to Massilia at the head of a consular army to fend off the tribe of the Saluvii.

Conquest of Narbonese Gaul

The Massilians ranked among Rome’s most longstanding allies.

In 154 BC they had already called on Rome for help against Ligurian raiders. The consul Opimius had been sent with an army to fend off the invaders.

It must be noted that since 173 BC Liguria was nominally a Roman territory. The marauders troubling the Massilians seem to be been tribes of the same Ligurian people, yet situated west of the Alps.

Now, in 125 BC, the Massilians once more called for help. Rome had thus far always maintained a policy of not seeking any territory in this area of southern Gaul. Things however, were about to change.

The man sent forth to the aid of Massilia was Marcus Fulvius Flaccus, whom the senate wanted out of the way for entirely political purposes. Flaccus led an army across the Alps, subduing first the Saluvii who were attacking the Massilians and then another allied Ligurian tribe in a campaign lasting two years.

The following two years a new commander, C. Sextus Calvinus, reduced the last remnants of Ligurian resistance in the area.

To further secure the area, the colony of Roman veterans was founded at Aquae Sextiae (Aix).

It soon proved why Rome had hitherto stayed out of this area. Fighting one enemy inevitably embroiled you in conflict with another.

The Celtic tribe of the Allobroges refused to hand over a Ligurian chieftain who had sought refuge. The tribe of the Aedui, previously Roman allies – or at least Massilian ones, – now also turned hostile.

In 121 BC proconsul Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus defeated the Allobroges at Vindalium. The Gauls it is said were panicked by the advance of the Roman elephant corps.

The Allobroges appealed for help to the most powerful Gallic tribe, the Arverni. Bituitus, the king of the Arverni, then put a gigantic army into the field to crush the Roman forces. A Roman army of 30,000, led by consul Quintus Fabius Maximus, met a joint force of Arverni and Allobroges totally no less than 180,000 men.

We do not know much of the battle which followed, but that it took places at the confluence of the river Rhodanus (Rhone) and the river Isara (Isere).

As the Roman force succeeded in breaking the foe, chaos ensued among the Gauls. The two boat bridges which they had built to cross the Rhodanus (Rhone) broke as the stampeding Gallic army sought to cross them.

If true or not is hard to tell, but the Romans reported their own losses to be 15 whilst claiming to have slain 120,000. Either way, the Battle of the river Isara was a crushing victory (121 BC). It secured for Rome all the territory from Geneva to the river Rhone.

Domitius Ahenobarbus, to whom command fell again on Fabius’ departure, concluded the settlement of the area (120 BC).

A formal alliance was agreed with the tribe of the Aedui to the north.

King Bituitus of the Arverni was taken captive despite a promise of safe conduct and sent to Rome. As the Arverni sued for peace the southern range of Gaul to the east of the Rhone, all the way to the Pyrenees fell under Roman rule, bringing under Roman control important regional towns such as Nemausus (Nimes) and Tolosa (Toulouse).

Domitius now saw to the construction of a road from the river Rhone to the Pyrenees, along the course of which Roman veterans were settled in a new colony called Narbo. The whole territory eventually was to become the province of Gallia Narbonensis (or Gallia Transalpina).

The Jugurthine War

In 118 BC the king of Numidia, Micipsa, died, leaving the crown to his young sons Hiempsal and Adherbal jointly with a much older nephew, Jugurtha, who was an experienced soldier.

Jugurtha arranged the assassination of Hiempsal, whilst Adherbal fled for his life and appealed to the senate.

The senate decided to send a commission to Numidia to divide he kingdom between the two claimants. Jugurtha appeared to bribe the commission’s leader, Opimius, who returned to Rome a richer man, after awarding the greater and wealthier part of Numidia to Jugurtha. Though this was not enough for the ambitious Jugurtha who then marched on the territory of Adherbal and had him murdered, too.

Rome was outraged. Rome’s judgement had simply been swept aside. Under the consul L Calpurnius Bestia troops were sent to Numidia to deal with the usurper. But the campaign was ineffective from the start, the Roman heavy infantry struggling to make any impression on the nimble Numidian horsemen.

Back in Rome eventually the comitia tributa to halt the campaign to have Jugurtha summoned to Rome to give evidence against any senators who were alleged to have accepted bribes from him. For this he was assured safe-conduct, meaning he was promised no to be charged or in any way harmed himself. But, once Jugurtha had arrived in Rome, these legal proceedings were stopped by a Tribune of the People who sought to avoid a political scandal.

So effective were Jugurtha’s methods that even while he was in Rome he had another cousin murdered in the city.

This was too much, and he was ordered to depart.

‘A city for sale !’ he is said to have sneered as he left.

More troops were now sent to Africa to deal with the usurper. though the campaign was so ill managed that a commission of inquiry was held, which revealed such dire scandals of widespread bribery and corruption that three ex-consuls, one being Opimius, retired into exile. Instead Quintus Metellus and Gaius Marius, both known not only for their ability as well as their for being virtually incorruptible, were sent out to Africa to take command of the troops (109 BC).

Metellus was a good soldier who conducted his campaigns with skill and vigour, but Jugurtha, a master of the arts of guerilla warfare, held out against him. Marius, a better soldier than Metellus, returned to Rome to stand for the consulship, claiming that if the command were given to him the war would be ended at once.

In fact, by the time he returned to Africa as consul to supersede Metellus, it appeared that Jugurtha was beaten. Metellus went home bitterly disappointed at having had his victory snatched from him. But Jugurtha was not finished yet.

Marius could not catch him, and he found a dubious ally or protector in his neighbour Bocchus, king of Mauretania. Finally it was the diplomatic skill of the quaestor Lucius Cornelius Sulla that induced Bocchus to betray Jugurtha to the Romans and to a miserable death at Rome. But the conquest was credited to Marius.

Gaius Marius and his Reforms of the Roman Army

Before Marius was back in Rome he was re-elected to the consulship (104 BC), though the law forbade re-election and required the candidate to be present in Rome.

But Marius was the soldier of the hour, and the hour demanded Rome’s finest soldier of the day.

For during the Numidian war a tremendous menace had been gathering on the northern frontiers of Italy. The German tribes were making their first appearance on the stage of history.

The advance hordes of the Teutones and the Cimbri had rolled past the Alps and poured into Gaul, flooding down the valley of the Saône and the Rhône and also setting in motion the Helvetic (Swiss) Celts. They defeated the Roman consul Silanus in 109 BC and in 107 BC another consul, Cassius, was trapped by the Helvetii and lost his army and his life. In 105 BC the forces of the pro-consul Caepio and the consul Mallius were annihilated by the Cimbri at the Battle of Arausio (Orange), ancient sources estimating the the losses up to even 80’000 or 100’000 men.

Then for no apparent reason the tide relented for a moment.

Rome, desperate to use the time, turned to Marius, placing control and reorganization of her armies in his hands and making him consul year after year. And Marius did the unthinkable.

Marius reorganizes the Army

For a primarily agricultural society such as Rome to be a perpetual war machine is to attempt to combine two incompatibles.

What Tiberius Gracchus had tried to halt when he was tribune in 133 BC was a trend which had begun centuries earlier and which, by the very success with which Rome had conducted military operations, had become a vicious circle.

Ancient armies were armed by peasant farmers. A society constantly at war required a constant flow of conscripts. Smallholdings fell into disuse because there was no one to tend to them. As Roman conquests spread through the Mediterranean lands, even more men were required, and wealth and cheap corn poured back into Rome, much of it into the hands of entrepreneurs, who carved out vast areas for vegetables, vines, olives and sheep farming, all managed by slave labour. The dispossessed rural poor, became the urban poor – so becoming ineligible for military service as no longer being nominal property holders.

Not only was there therefore a shortage of recruits, but the soldiers had nothing to return to between campaigns or at the end of their service. A working solution to this problem was finally devised by Gaius Marius, once consul in 108 BC. He introduced the Roman army as it came to be known and feared all across the Europe and the Mediterranean.

Rather than conscripting from Roman landowners he recruited volunteers from the urban poor. Once the idea of a professional army of mercenaries was introduced, it never remained until the very end of the Roman Empire. Furthermore, Marius introduced the idea of granting soldiers allotments of farmland after they hand served their term.

Marius defeats the Northmen

Marius’ revolution in the army came only just in time.

In 103 BC the Germans were again massing at the Saône, preparing to invading Italy by crossing the Alps in two different places. The Teutones crossed the mountains in the west, the Cimbri did so in the east.

In 102 BC Marius, consul for the fourth time, annihilated the Teutones at Aquae Sextiae beyond the Alps, while his colleague Catullus stood guard behind them.

Next in 101 BC the Cimbri poured through the eastern mountain passes into the plain of the river Po. They in turn were annihilated by Marius and Catulus at Campi Raudii near Vercellae.

Marius reaped the benefit of his joint victory with Catulus, by being elected to his sixth consulship.

The Second Slave War

The atrocities of the First Slave War were anything but forgotten when in 103 BC the slaves of Sicily dared to revolt again. That after the cruelty in the aftermath of the first conflict they dared to rise again, hints how bad their conditions must have been.

They fought so stubbornly that it took Rome 3 years to stamp out the revolt.

The Social War

In 91 BC the moderate members of the senate allied themselves with Livius Drusus (the son of that Drusus who had been used to undermine Gaius Gracchus’ popularity in 122 BC) and aided him in his election campaign. If the honesty of the father is open to doubt, that of the son is not. As tribune he proposed to add to the senate an equal number of equestrians, and to extend Roman citizenship to all Italians and to grant the poorer of the current citizens new schemes for colonization and a further cheapening of the corn prices, at the expense of the state.

Though the people, the senators and the knights all felt that they would be conceding too many of their rights for too little. Drusus was assassinated.

Despite his eventually loss of popularity his supporters had stood by Drusus loyally. The opposition Tribune of the People, Q. Varius, now carried a bill declaring that to have supported the ideas of Drusus was treason. The reaction by Drusus’ supporters was violence.

All resident Roman citizens were killed by an enraged mob at Asculum, in central Italy. Worse still, the ‘allies’ (socii)of Rome in Italy, the Marsi, Paeligni, Samnites, Lucanians, Apulians all broke into open revolt.

The ‘allies’ had not planned any such rising, far more it was a spontaneous outburst of anger against Rome. But that meant they were unprepared for a fight. Hastily they formed formed a federation. A number of towns fell into their hands at the outset, and they defeated a consular army. But alas, Marius took led an army into battle and defeated them. Though he didn’t – perhaps deliberately – crush them.

The ‘allies’ had a strong party of sympathizers in the senate. And these senators in 89 BC managed to win over several of the ‘allies’ by a new law (the Julian Law – lex Iulia) by which Roman citizenship was granted to ‘all who had remained loyal to Rome (but this most likely also included those who laid down their arms against Rome).

But some of the rebels, especially the Samnites, only fought the harder. Though under the leadership of Sulla and Pompeius Strabo the rebels were reduced on battlefield until they held out only in a few Samnite and Lucanian strongholds.

Was the city of Asculum in particular dealt with severely for the atrocity committed there, the senate tried to bring an end to the fighting by conceding citizenship to by granting citizenship to all who laid down their arms within sixty days (lex Plautia-Papiria).

The law succeeded and by the beginning of 88 BC the Social War was at an end, other than for a few besieged strongholds.

Sulla (138-78 BC)

Lucius Cornelius Sulla was yet another nail in the coffin of the Republic, perhaps much in the same mould as Marius.

Having already been the first man to use Roman troops against Rome itself.

And much like Marius he, too, should make his mark in history with reforms as well as a reign of terror.

Sulla takes Power

In 88 BC the activities of king Mithridates of Pontus called for urgent action. The king had invaded the province of Asia and massacred 80’000 Roman and Italian citizens. Sulla, as elected consul and as the man who had won the Social War, expected the command, but Marius wanted it, too. The senate appointed Sulla to lead the troops against Mithridates.

But the tribune Sulpicius Rufus (124-88 BC), a political ally of Marius, passed through the concilium plebis an order calling for the transfer of command to Marius. Peaceful as these happenings may sound, they were accompanied by much violence.

Sulla rushed straight from Rome to his still undisbanded troops of the Social War before Nola in Campania, where the Samnites were still holding out.

There, Sulla appealed to the soldiers to follow him. The officers hesitated, but the soldiers did not. And so, at the head of six Roman legions, Sulla marched on Rome. He was joined by his political ally Pompeius Rufus. They seized the city gates, marched in and annihilated a force hastily collected by Marius.

Sulpicius fled but was discovered and killed. So, too, did Marius, by now 70 years old, flee. He was picked up at the coast of Latium and sentenced to death. But as no one could be found prepared to do the deed he was instead hustled onto a ship. He ended up in Carthage where he was ordered by the Roman governor of Africa to move on.

Sulla’s first Reforms

While he still held the command of the military in his hands, Sulla used the military assembly (comitia centuriata) to annul all legislation passed by Sulpicius and to proclaim that all business to be submitted to the people should be dealt with in the comitia centuriata , while nothing at all was to be brought to the people before it received senatorial approval.

In effect this took away any which the tribal assembly (comitia tributa) and the plebeian assembly (concilium plebis) possessed. Also it reduced the power of the tribunes, who until then had been able to use the people’s assemblies to by-pass the senate.

Naturally, it also increased the power of the senate.

Sulla did not interfere in the elections for the offices of consul, but to demand from the successful candidate, L. Cornelius Cinna, not to reverse any of the changes he had made.

This done Sulla left with his forces to fight Mithridates in the east (87 BC).

Marius and Cinna take Power

Though in his absence Cinna revived the legislation and the methods of Sulpicius. When violence broke out in the city, he appealed to the troops in Italy and practically revived the Social War. Marius returned form exile and joined him, though he appeared more intent on revenge than on anything else.

Rome lay defenceless before the conquerors. The city’s gates to Marius and Cinna. In the week’s reign of terror which followed, Marius wreaked his revenge on his enemies.

After the brief but hideous orgy of blood-lust which alarmed Cinna and disgusted their allies in the senate, Marius seized his seventh consulship without election. But he died a fortnight later (January, 87 BC).

Cinna remained sole master and consul of Rome until he was killed in the course of a mutiny in 84 BC.

The power fell to an ally of Cinna’s, namely Cn. Papirius Carbo.

First Mithridatic War

When the Social War had broken out, Rome was fully occupied with its own affairs. Mithridates VI, king of Pontus, used Rome’s preoccupation to invade the province of Asia. Half of the province of Achaea (Greece), Athens taking the lead, rose against its Roman rulers, supported by Mithridates.

When Sulla arrived at Athens, the city’s fortifications proved too much for him to charge. Instead he starved them out, whilst his lieutenant, Lucius Lucullus, raised a fleet to force Mithridates out of the Aegean Sea.

Early in 86 BC Athens fell to the Romans.

Though Archelaus, the ablest general of Mithridates, now threatened with a large army from Thessaly. Sulla marched against him with a force only a sixth in size and shattered his army at Chaeronea.

A Roman consul, Valerius Flaccus, now landed with fresh forces in Epirus, to relieve Sulla of his command. But Sulla had no intention of relinquishing his power. News reached him that general Archelaus had landed another huge force. Immediately he turned southwards and destroyed this force at Orchomenus.

Meanwhile Flaccus, avoiding a conflict with Sulla, headed toward Asia seeking to engage Mithridates himself. Though he never reached it. His second-in-command, C. Flavius Fimbria, led a mutiny against him, killed him and assumed command himself. Fimbria crossed the straights and started operations in Asia.

Meanwhile Sulla opened negotiations with the defeated Archelaus. An conference was arranged in 85 BC between Sulla and Mithridates and a treaty was struck by which Mithridates was to surrender his conquests to Rome and retreat behind the borders he’d held before the war. So too, was Pontus to hand over a fleet of seventy ships and pay a tribute.

It now remained to settle the problem of Fimbria, who could only hope to excuse his mutiny with some success. With the war over and Sulla closing on him with his troops, his situation was hopeless. Alas, his troops deserted him and Fimbria committed suicide.

Therefore, in 84 BC, his campaigns a total success, Sulla could start making his was back to Rome.

Sulla becomes Dictator

Sulla should arrive back in Italy in the spring of 83 BC and marched on Rome determined to restore his will upon the city.

But the Roman government controlled greater troops than his own, more so the Samnites wholeheartedly flung themselves into the struggle against Sulla, who to them represented senatorial privilege and the denial of citizenship to the Italians.

Alas, it came to the decisive Battle of the Colline Gate in August 82 BC, where fifty thousand men lost their lives.

Sulla emerged victorious at the Battle of the Colline Gate and so became the master of the Roman world.

Sulla in no way lacked any of the blood-lust displayed by Marius. Three days after the battle he ordered all of the eight thousand prisoners taken on the battle field to be massacred in cold blood.

Soon after Sulla was appointed dictator for so long as he might think fit to retain office.

He issued a series of proscriptions – lists of people who were to have their property taken and who were to be killed. The people killed in these purges were not only supporters of Marius and Cinna, but so too people Sulla simply disliked or held a grudge against.

The lives of the people of Rome were entirely in Sulla’s hands. He could have them killed or he could spare them. One he chose to spare was a dissolute young patrician, whose father’s sister had been the wife of Marius, and who himself was the husband of Cinna’s daughter – Gaius Julius Caesar.

Sulla’s second Reforms

Sulla took charge of the constitution in 81 BC. All the power of the state would henceforth lay in the hands of the senate.The Tribunes of the People and the people’s assemblies had been by the democrats to overthrow the senate. Tribunes were to be barred from all further office and the assemblies were deprived of the power of initiating any legislation. The senatorial control of the courts was restored at the expense of the equestrians.

There were to be no more repeated consulships, like those of Marius and Cinna.

Consuls were not to hold military command until, after their year of office, they went abroad as proconsuls, when their power could only be exercised in their respective province.

Then in 79 BC Sulla lay down his powers as dictator and devoted his remaining months to the enjoyment of wild parties. He died in 78 BC.

Although the Roman Republic technically still had some fifty years to go, Sulla pretty much represents its demise. He should stand as an example to others to come that is was possible to take Rome by force and rule it, if only one was strong and ruthlessness enough to do what ever deeds were required.

The Age of Caesar

The twenty years following Sulla’s death saw the rise of three men who, if Rome’s founders were truly suckled by a she-wolf, surely had within them the stuff of wolves.

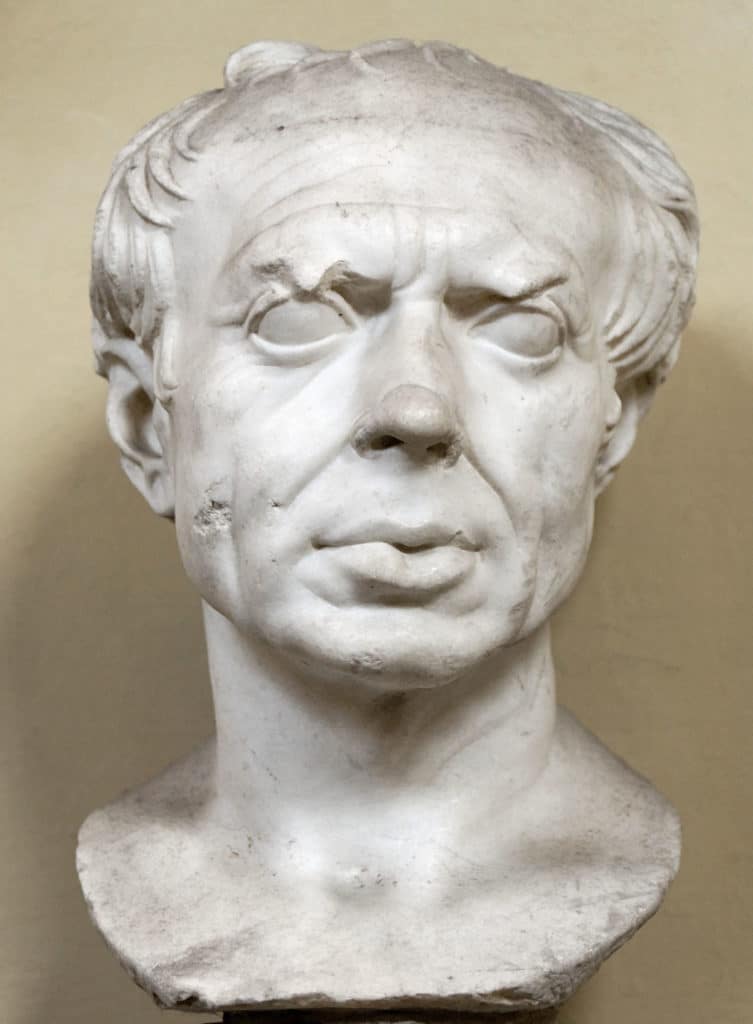

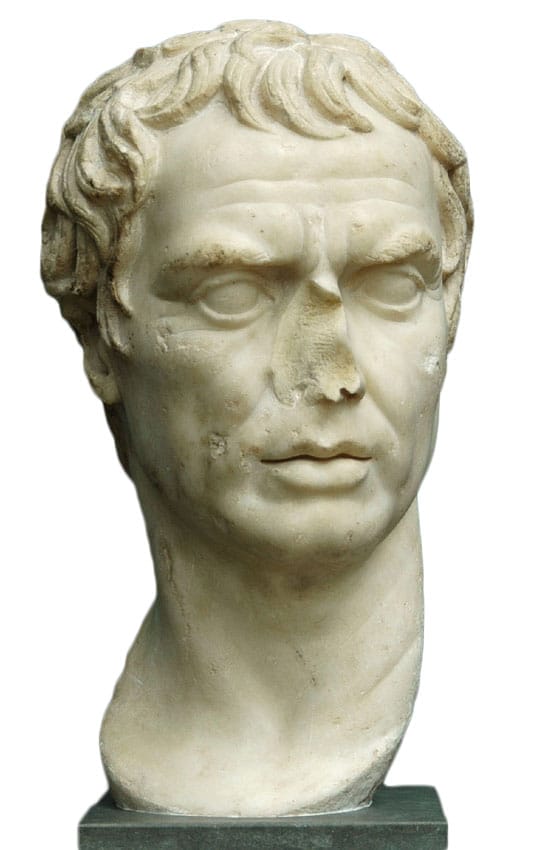

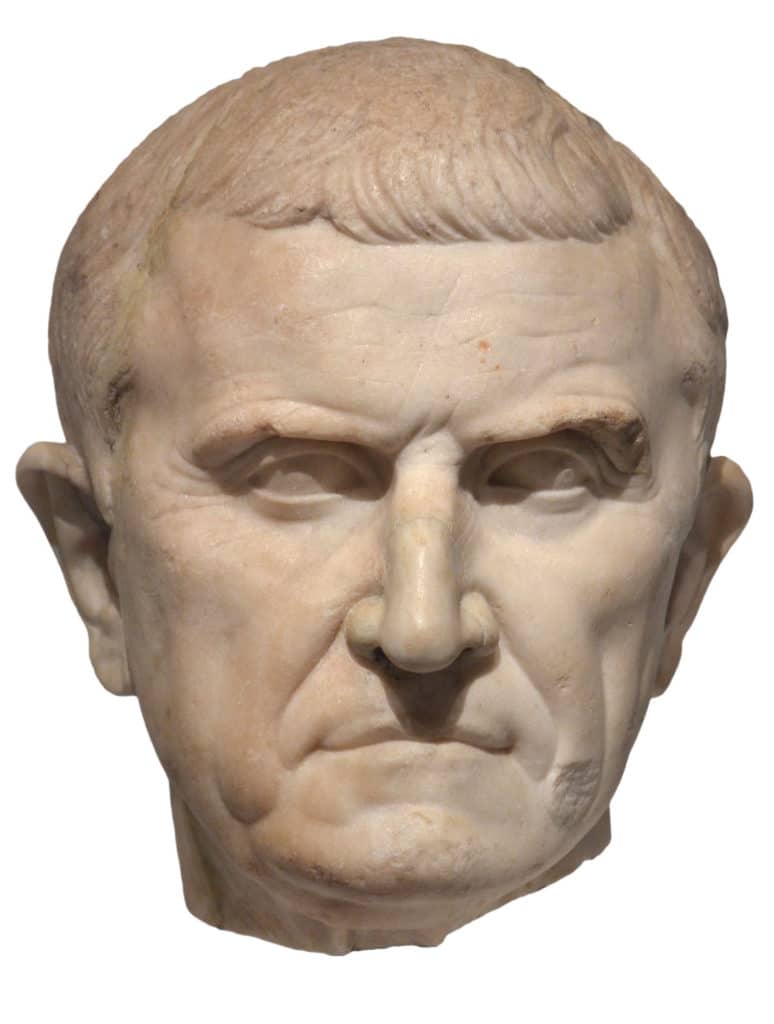

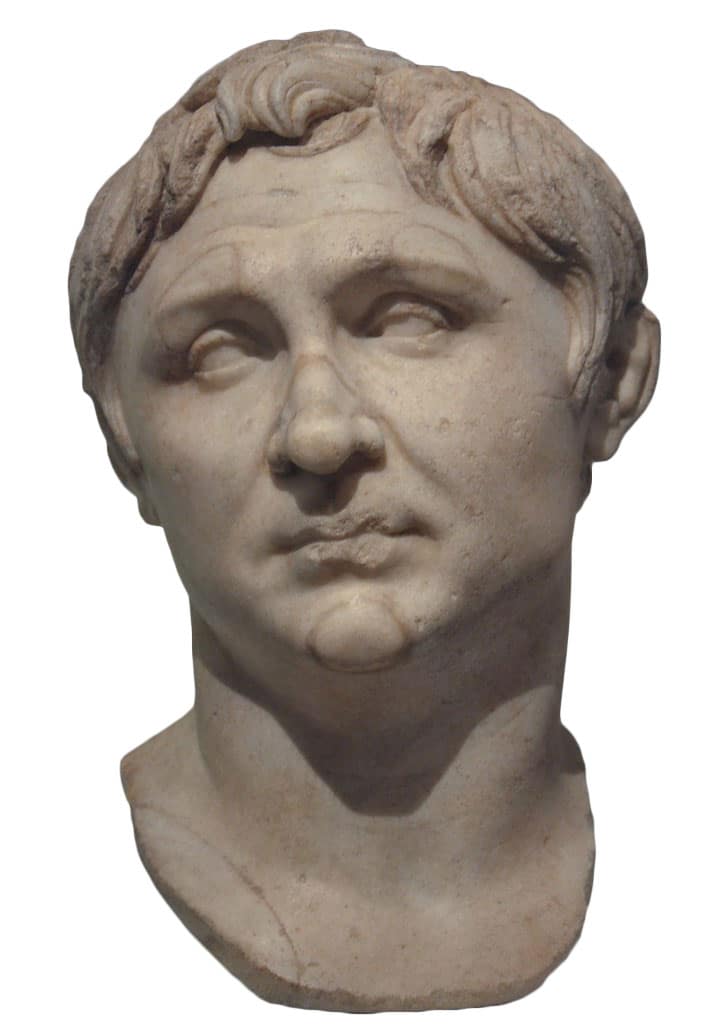

The three were Marcus Licinius Crassus (d. 53 BC), one of Rome’s richest men ever. Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (106-48 BC), known as Pompey the Great, perhaps the greatest military talent of his time, and Gaius Julius Caesar (102-44 BC), arguably the most famous Roman of all times.

A fourth man was Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC), is generally understood to have been the greatest orator in the entire history of the Roman Empire. All four were stabbed to death within ten years of each other.

The Rise of Crassus and Pompey

Two men had risen to prominence as supporters of Sulla. One was Publius Licinius Crassus (117-53 BC), who had played a major part in the victory of the Colline Gate for Sulla. The other, Gnaeus Pompeius (106-48 BC), known to the modern historians as Pompey, was a youthful commander of remarkable military talents. Such talents in fact that Sulla had entrusted him with the suppression of the Marians (the supporters of Marius) in Africa. This command he had fulfilled so satisfactorily that it had earned him the complimentary title ‘Magnus’ (‘the Great’) from the dictator. Crassus had no little ability, but he chose to concentrate it on the acquisition of wealth.

Sulla was hardly dead, when the inevitable attempt to overturn his constitution was made by the consul Lepidus, the champion of the popular party. when he took up arms however, he was easily crushed (77 BC).

In one quarter, the Marians had not yet been suppressed. The Marian Sertorius had retreated to Spain when Sulla returned to Italy, and there he had been making himself a formidable power, partly by rallying the Spanish tribes to join him as their leader.

He was very much more than a mere match for the Roman forces sent to deal with him. Pompey, charged with the business of dealing with him in 77 BC, fared not much better than his predecessors.

More worryingly the menacing king Mithridates of Pontus, no longer in awe of Sulla, was negotiating with Sertorius with the intention of renewing the war in 74 BC.

But this alliance came to nothing as Sertorius was assassinated in 72 BC. With Sertorius” death the defeat of the Marians in Spain posed no great difficulty to Pompey anymore.

Pompey could now return home to Rome to claim and receive credit, scarcely deserved, for having succeeded were others had failed.

Third Slave War

Slaves were trained as gladiators, and in 73 BC such a slave, a Thracian named Spartacus, broke out of a gladiator training camp at Capua and took refuge in the hills. The number of his band swelled rapidly and he kept his men well in hand and under strict discipline and routed two commanders who were sent to capture him. In 72 BC Spartacus had so formidable force behind him, that two consular armies were sent against him, both of which he destroyed.

Pompey was in the west, Lucullus in the east. It was Crassus who at the head of six legions at last brought Spartacus to bay, shattered his army, and slew him on the field (71 BC).

Five thousand of Spartacus’ men cut their way through the lines and escaped but only to end up in the very path of Pompey’s army returning from Spain.

Pompey claimed the victory of quelling the Slave war for himself, adding to his questionable glories gained in Spain. Crassus, seeing that the popular soldier might be useful to him, did not quarrel.

Crassus and Pompey joint Consuls

So powerful were the positions of the two leaders, that they felt secure enough to challenge Sulla’s constitution. Both by the terms of Sulla’s laws were barred from standing for the consulship. Pompey was too young and Crassus was required to let a year pass between his position as praetor before he could stand for election.

But both men stood and both were elected.

As consuls, during 70 BC, they procured the annulment of the restrictions imposed on the office of Tribune of the People. Thereby they restored the lost powers of the tribal assembly. The senate dared not refuse their demands, knowing an army behind each of them.

Third Mithridatic War

In 74 BC king Nicomedes of Bithynia died without heirs. Following the example of Attalus of Pergamum he left his kingdom to the Roman people. But with Sulla dead, king Mithridates of Pontus clearly felt his most fearsome enemy had vanished from the scene and revived his dreams of creating his own empire. Nicomedes’ death provided him with an excuse to start a war. He supported a false pretender to the throne of Bithynia on whose behalf he then invaded Bithynia.

At first the consul Cotta failed to make any significant gains against the king, but Lucius Lucullus, formerly the lieutenant of Sulla in the east, was soon dispatched to be governor of Cilicia to deal with Mithridates.

Though provided only with a comparatively small and undisciplined force, Lucullus conducted his operations with such skill that within a year he had broken up the army of Mithridates without having had to fight a pitched battle. Mithridates was driven back into his own territory in Pontus. Following a series of campaigns in the following years Mithridates was forced to flee to king Tigranes of Armenia.

Lucullus’ troops had subjugated Pontus by 70 BC. Meanwhile however Lucullus, trying to sort out matters in the east realized that the cites of the province of Asia were being strangled by the punitive tributes they had to pay to Rome. In fact they had to borrow money to be able to pay them, leading to an ever growing spiral of debt.

In order to alleviate this burden and to return the province back to prosperity he scaled down their debts to Rome from the huge total of 120’000 talents to 40’000.

This inevitably earned him the enduring gratitude of the cities of Asia, but it also drew upon him the undying resentment of the Roman moneylenders who had until profiteered from the plight of the Asiatic cities.

In 69 BC Lucullus, having decided that until Mithridates was captured the conflict in the east could not be resolved, advanced into Armenia and captured the capital Tigranocerta. In the next year he routed the forces of the Armenian king Tigranes. but in 68 BC, paralysed by the mutinous spirit of his depleted troops he was forced to withdraw to Pontus.

Pompey defeats the Pirates

In 74 BC Marcus Antonius, father of the famous Mark Antony, had been given special powers to suppress the large-scale piracy in the Mediterranean. But his attempts had ended in dismal failure. After Antonius’ death, the consul Quintus Metellus was set upon the same task in 69 BC. Matters indeed did improve, but Metellus’ role should be cut shorts, as Pompey in 67 BC decided he wanted the position. Thanks to no small part to the support of Julius Caesar, Pompey was given the task, despite opposition by the senate.

A commander free to do as he wished and with nearly unlimited resources, Pompey accomplished in only three months what no one else had managed. Spreading his fleet systematically across the Mediterranean, Pompey swept the sea clean from end to end. The pirates were destroyed.

Pompey against Mithridates

By popular acclaim, fresh from his brilliant triumph over the pirates, Pompey was given supreme and unlimited authority over the whole east. His powers were to be in his hands until he himself should be satisfied with the completeness of the settlement he might effect.

No Roman, other than Sulla, had ever been given such powers. From 66 to 62 BC Pompey should remain in the east.

In his first campaign Pompey forced Mithridates to fight him, and routed his forces on the eastern border of Pontus. Mithridates fled, but was refused asylum by Tigranes of Armenia who, after the onslaught by Lucullus, evidently feared Roman troops. Instead Mithridates fled to the northern shores of the Black Sea. There, beyond reach of the Roman forces, he began to form plans of leading the barbarian tribes of eastern Europe against Rome. That ambitious project, however, was brought to an end as his own son Pharnaces. In 63 BC, a broken old man, Mithridates killed himself.

Meanwhile Tigranes, eager to come to an arrangement with Rome, had already withdrawn his support for Mithridates and had pulled back his troops based in Syria. when Pompey marched into Armenia, Tigranes submitted to Roman power. Pompey seeing his task completed, saw no reason to occupy Armenia itself. Far more he left Tigranes in power and returned to Asia Minor (Turkey), where he began the organization of the new Roman territories.

Bithynia and Pontus were formed into one province, and the province of Cilicia was enlarged. meanwhile the minor territories on the border, Cappadocia, Galatia and Commagene were recognized as being under Roman protection.

Pompey annexes Syria

When in 64 BC Pompey descended from Cappadocia into northern Syria he needed little more than assume sovereignty on behalf of Rome. Ever since the collapse of the kingdom of the Seleucids sixty years previously, Syria had been ruled by chaos. Roman order was hence welcomed. The acquisition of Syria brought the eastern borders of the empire to the river Euphrates, which should hence traditionally be understood as the boundary between the two great empires of Rome and Parthia.

In Syria itself Pompey is said to have founded or restored as many as forty cities, settling them with the many refugees of the recent wars.

Pompey in Judaea

However, to the south things were different. The princes of Judaea had been allies of Rome for half a century.

But Judaea was suffering a civil war between the two brothers Hyrcanus and Aristobulus. Pompey was hence asked to help quell their quarrels and help decide the matter of rule over Judaea (63 BC).

Pompey advised in favour of Hyrcanus. Aristobulus gave way to his brother. But his followers refused to accept and locked themselves up in the city of Jerusalem. Pompey hence besieged the city, conquered it after three months and left it to Hyrcanus. But his troops having effectively put Hyrcanus in power, Pompey left Judaea no longer an ally but a protectorate, which paid a tribute to Rome.

The Cataline Conspiracy

During the five years of Pompey’s absence in the east Roman politics were as lively as ever.

Julius Caesar, the nephew of Marius and son-in-law of Cinna, was courting popularity and steadily rising in power and influence.

However, among the hot-heads of the anti-senatorial party was Lucius Sergius Catalina (ca. 106 – 62 BC) a patrician who was at least reputed to have no scruples in such matters as assassination.

On the other side the ranks of the senatorial party were joined by the most brilliant orator of the day, Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 – 43 BC).

In 64 BC Catalina stood as a candidate for the consulship, having just been barely acquitted in the courts on a charge of treasonable conspiracy.

Though Cicero was not popular with the upper class senators of the old families, his party nominated him as their candidate – if only to prevent Catalina from winning the seat. Cicero’s rhetoric won day and secured him the post of consul.

But Catalina was not a man to take defeat easily.

While Caesar continue to court popularity, managing even to secure election to the dignified office of pontifex maximus ahead of the most eminent senatorial candidates, Catalina began to plot.

The intrigue was afoot in 63 BC, and yet Catalina did not intend to move until he had attained the consulship. He also didn’t feel sufficiently ready to strike yet.

But all should come to nothing as some information about his plans was passed on to Cicero. Cicero went to the senate and presented what evidence he had, of plans being afoot.

Catalina escaped to the north to head the intended rebellion in the provinces, leaving his accomplices to carry out the programme arranged for the city.

Cicero, by now having been granted emergency powers by the senate, obtained correspondence between Catalina and the Gallic tribe of the Allobroges. The principal conspirators named in the letter were arrested and condemned to death without trial.

Cicero told the whole story to the people gathered in the forum amid frantic applause. In the city of Rome the rebellion had been quashed without a fight.

But in the country Catalina fell fighting indomitably in early 62 BC at the head of the troops he had succeeded in raising.

For the moment at least civil war had been averted.

The first Triumvirate

With Pompey about to return to Rome, no one knew what the conqueror of the east intended to do. Both Cicero and Caesar wanted his alliance. But Caesar knew how to wait and turn events in his favour. At present Crassus with his gold was more important then Pompey with his men. The money of Crassus enabled Caesar to take up the praetorship in Spain, soon after Pompey’s landing at Brundisium (Brindisi).

However, many people took comfort when Pompey instead of remaining at the head of his army dismissed his troops. He was not minded to play the part of dictator.

Then in 60 BC Caesar returned from Spain, enriched by the spoils of successful military campaigns against rebellious tribes. He found Pompey showing little interest in any alliance with Cicero and the senatorial party. Instead an alliance was forged between the popular politician, the victorious general and the richest man in Rome – the so-called first triumvirate – between Caesar, Pompey and Crassus.

The reason for the ‘first triumvirate is to be found in the hostility the populists Crassus Pompey and Caesar faced in the senate, in particularly by the likes of Cato the Younger, Cato the Elder’s great-grandson. Perhaps his famous namesake before him Cato the Younger was a (self-)righteous, but talented politician. A fatal mix, if surrounded by wolves of the caliber of Crassus, Pompey and Caesar. He became one of the leaders in the senate, where he particularly rounded on Crassus, Pompey and Caesar. Alas, he even fell out with Cicero, the greatest speaker of the house by far.

The ‘first triumvirate was, rather than a constitutional office or a dictatorship imposed by force, an alliance of the three main popular politicians; Crassus, Pompey and Caesar.

They helped each other along, guarding each other’s backs from Cato the Younger and his attacks in the senate.

With Pompey and Crassus supporting him Caesar was triumphantly elected consul.

The partnership with Pompey was to be sealed in the following year by the marriage between Pompey and Caesar’s daughter Julia.

The first Consulate of Julius Caesar

Caesar used his year as consul (59 BC) to further establish his position. A popular agrarian law, As his first act in office Caesar brought proposed a new agrarian law which gave lands to the veteran soldiers of Pompey and poor citizens in Campania.. Though opposed by the senate, but supported by Pompey as Crassus, the law was passed in the tribal assembly, after a detachment of Pompey’s veterans had by physical force swept away any possible constitutional opposition. The populace were gratified and the three triumvirs now had a body of loyal and grateful veteran soldiers to call on in case of trouble.

Pompey’s organization of the east was finally confirmed, having been in doubt until then. And finally Caesar secured for himself an unprecedented term of five years for the proconsulship of Cisalpine Gaul and Illyricum. The senate, hoping to be well rid of him, added to his territories Transalpine Gaul (Gallia Narbonensis) where serious trouble was brewing.

Before his departure though Caesar saw to it that the political opposition lay in tatters. The austere and uncompromising Cato the Younger (95-46 BC) was dispatched to secure the annexation of Cyprus. Meanwhile the arch-enemy of Cicero, Publius Claudius (known as Clodius), was aided in obtaining the position of Tribune of the People, whilst Cicero himself was forced into exile in Greece for having illegally killed without trial the accomplices of Catalina during the Cataline Conspiracy.

Caesar defeats the Helvetii, the Germans and the Nervii

In the first year of his governorship of Gaul 58 BC, Caesar’s presence was urgently required in Transalpine Gaul (Gallia Narbonensis) because of the movement among the Teutonic tribes which was displacing the Helvetic (Swiss) Celts and forcing them into Roman territory. the year 58 BC was therefore first occupied with a campaign in which the invaders were split in two and their forces so heavily defeated that they had to retire to their own mountains.

But no sooner was this menace dealt with another loomed on the horizon. The fierce Germans tribes (Sueves and Swabians) were crossing the Rhine and threatening to overthrow the Aedui, the Gallic allies of Rome on the northern borders of the Roman province of Transalpine Gaul.

The German chief, Ariovistus, apparently envisaged the conquest of entire Gaul and its partition between himself and the Romans.

Caesar led his legions to the help of the Aedui and utterly defeated the German force, with Ariovistus barely escaping across the Rhine with what was left of his forces.

With the Germans driven back, fear was aroused in Gaul of a general Roman conquest. The Nervii, who were the leading tribe of the warlike Belgae in the north-east of Gaul prepared an attack on Rome’s forces. But Caesar received warning from friends in Gaul and decided to attack first, invading Nervian territory in 57 BC.

The Nervii fought heroically and for some time the outcome of the decisive battle uncertain, but eventually Caesar’s victory proved overwhelming. It was followed by a general submission of all the tribes between the river Aisne and the Rhine.

Disorder in Rome under Clodius

With Julius Caesar campaigning in Gaul, Clodius exercised his powers as the virtual king of Rome with neither Pompey nor Crassus interfering. Among his measures was a law which distributed corn no longer at half price but for free to the citizens of Rome.

But his conduct was generally reckless and violent, as he employed a large gang of thugs and troublemakers to enforce his will. So much so, that it aroused the anger of Pompey who the following year (57 BC) used his influence to enable the return of Cicero to Rome. Did the supporters of Clodius protest in a violent riot then this was met with equal brute force by Pompey, who organized his own band of thugs, made up partially of veterans of his army, which under the guidance of the tribune T. Annius Milo took to the streets and beet Clodius’ ruffians at their own game.

Cicero, finding himself still very popular on his return to Rome, proposed – perhaps feeling indebted – that Pompey should be granted dictatorial powers for the restoration of order. But only partial, not total power was conveyed upon Pompey, who himself seemed little tempted in acting as a policeman in Rome.

Conference of the Triumvirs in Luca

With Clodius reduced in power and influence, the senate was stirring again, seeking to gain back some power from the three triumvirs. So in 56 BC a meeting was held at Luca in Cisalpine Gaul by the three men, determined to hold onto their privileged position.

The result of the meeting was that Pompey and Crassus stood for the consulship again and were elected – largely due to the fact that Crassus’ son, who had been serving brilliantly under Caesar, was at no great distance from Rome with a returning legion.

Did Pompey and Crassus gain office in such way, then Caesar’s part of the bargain was that the two new consuls extended his term in office in Gaul by another five years (until 49 BC).

Caesar’s expeditions into Germany and Britain

Caesar went on, after the the conference of Luca to reduce the whole of Gaul to submission in the course of three campaigns – justified by initial aggression from the barbarians.

The two following years were occupied with expeditions and campaigns of an experimental kind. In 55 BC a fresh invasion of Germans across the Rhine was completely shattered in the neighbourhood of modern Koblenz and the victory was followed by a great raid over the river into German territory, which made Caesar decide that the Rhine should remain the boundary.

Gaul conquered and the Germans crushed, Caesar turned his attention to Britain. In 55 BC he led his first expedition to Britain, a land so far known only by the reports of traders.

The following year, 54 BC, Caesar led his second expedition, and reduced the south-east of the island to submission. But he decided that real conquest was not worth undertaking.

During that winter and the following year 53 BC, the year of the disaster of Carrhae, Caesar was kept occupied with various revolts in north-eastern Gaul.

Pompey sole consul in Rome

In 54 BC Pompey’s young wife had died and with her death had disappeared the personal link between him and his father-in-law Caesar.

Crassus had started for the east to take up governorship of Syria. Meanwhile Pompey did little. He simply watched with growing jealousy the successive triumphs of Caesar in Gaul.

In 52 BC things in Rome reached another point of crisis. During the previous two years the city had remained in a state of near anarchy.

Clodius, still the leader of the popular extremists, was killed in an violent brawl with the followers of Milo, the leader of the senatorial extremists. Pompey, was elected sole consul and was commissioned to restore order in the ever more riotous city of Rome.

In effect Pompey was left virtual dictator of Rome. A dangerous situation, considering Caesar’s presence in Gaul with several battle-hardened legions.

Pompey himself achieved a five year extension for his own position of proconsul of Spain, but – very controversially – he had a law passed by which Caesar’s term in Gaul would be cut short by almost a year (ending in March 49 instead of January 48 BC).

A reaction of Caesar’s was inevitable to such provocation, but he could not respond immediately, as a large scale revolt in Gaul demanded his full attention.

Disaster at Carrhae

In 55 BC Crassus had, during his consulship, in the aftermath of the conference at Luca, managed to secure himself the governorship of Syria. Phenomenally rich and renowned for greed, people saw this as yet another example of his appetite for money. The east was rich, and a governor of Syria could hope to be much the richer on his return to Rome.

But Crassus was for once, it appears, seeking more than mere wealth, although the promise of gold no doubt played a major part in his seeking the governorship of Syria. With Pompey and Caesar having covered themselves in military glory, Crassus craved for similar recognition.

Had his money bought him his power and influence so far, as a politician he had always been the poor relation to his partners in the triumvirate. There was only one way by which to equal their popularity and that was by equalling their military exploits.

Relations with the Parthians had never been good and now Crassus set out on a war against them. First he raided Mesopotamia, before spending the winter of 54/53 BC in Syria, when he did little to make himself popular by requisitioning from the Great Temple of Jerusalem and other temples and sanctuaries.

Then, in 53 BC, Crassus crossed the Euphrates with 35’000 men with the intention of marching on Seleucia-ad-Tigris, the commercial capital of ancient Babylonia. Large though Crassus’ army was, it consisted almost entirely of legionary infantry.

But for the Gallic horseman under the command of his son, he possessed no cavalry. An arrangement with the king of Armenia to supply additional cavalry had fallen foul, and Crassus was no longer prepared to delay any further.

He marched into absolute disaster against an army of 10’000 horsemen of the Parthian king Orodes II. The place where the two armies met, the wide open spaces of the low lying land of Mesopotamia around the city of Carrhae, offered ideal terrain for cavalry manoeuvres.

The Parthian horse archers could move at liberty, staying at a safe distance while taking shots at the helpless Roman infantry from a safe range. 25’000 men fell or were captured by the Parthians, the remaining 10’000 managed to escape back to Roman territory.

Crassus himself was killed trying to negotiate terms for surrender.

The Rebellion of Vercingetorix in Gaul

In 52 BC, just as Pompey’s jealousies reached their height, a great rebellion was organized in the very heart of Gaul by the heroic Arvernian chief Vercingetorix. So stubborn and so able was the Gallic chief that all Caesar’s energies were required for the campaign. On an attack on Gergovia Caesar even suffered a defeat, dispelling the general myth of his invincibility.

Taking heart from this, all Gallic tribes, except for three broke out in open rebellion against Rome. Even the allied Aedui joined the ranks of the rebels. But a battle near Dijon turned the odds back in favour of Caesar, who drove Vercingetorix into the hill-top city of Alesia and laid siege to him.

All efforts of the Gauls to relieve the siege were in vain. At Alesia the Gallic resistance was broken and Vercingetorix was captured. Gaul was conquered for good.

The whole of 51 BC was taken up by the organization of the conquered land and the establishment of garrisons to retain its control.

Caesar’s breach with Pompey

Meanwhile the party in Rome most hostile toward him was straining itself to the utmost to effect his ruin between the termination of his present appointment and his entry into a new post.

Caesar would be secure from attack if he passed straight from his position of proconsul of Gaul and Illyricum into the office of consul back in Rome. He was sure to win an election to that office, but the rules prohibited him from entering such a position till 48 BC (the rules stated that he had to wait for ten years after holding the office of consul in 59 BC !). If he could be deprived of his troops before that date, he could be attacked through the law courts for his questionable proceedings in Gaul and his fate would be sealed, while Pompey would still enjoy command over his own troops in Spain.

So far Caesar’s supporters in Rome delayed a decree which would have displaced Caesar from office in March 49 BC. But the problem was only delayed, not resolved. Meanwhile in 51 BC, two legions were detached from Caesar’s command and moved to Italy, to be ready for service against the Parthians in the east.

In 50 BC the question of redistributing the provinces came up for settlement. Caesar’s agents in Rome proposed compromises, suggesting that Caesar and Pompey should resign simultaneously from their positions as provincial governors, or that Caesar should only retain one of his three provinces.

Pompey refused, but proposed that Caesar should not resign until November 49 BC (which would still have left two months for his prosecution !). Caesar naturally refused. Having completed the organization of Gaul, he had now returned to Cisalpine Gaul in northern Italy with one veteran legion. Pompey, commissioned by a suspicious senate, left Rome to raise more troops in Italy.

In January 49 BC Caesar repeated his offer of a joint resignation. The senate rejected the offer and decreed that their current consuls should enjoy a completely free hand ‘in defence of the Republic’. Evidently they had resigned themselves to the fact that there was going to be a civil war.

Caesar was still in his province, of which the boundary to Italy was the river Rubicon. The momentous choice lay before him. Was he to submit and let his enemies utterly destroy him or was he to take power by force. He made his choice. At the head of one of his one legion, on the night of January 6, 49 BC, he crossed the Rubicon. Caesar was now at war with Rome.

Showdown between Casesar and Pompey

Pompey was not prepared for the sudden swiftness of his adversary. Without waiting for the reinforcements he had summoned from Gaul, Caesar swooped on Umbria and Picenum, which were not prepared to resist. Town after town surrendered and was won over to his side by the show of clemency and the firm control which Caesar held over his soldiers.

In six weeks he was joined by another legion from Gaul. Corfinium was surrendered to him and he sped south in pursuit of Pompey.

The legions Pompey had ready were the very legions which Caesar had led to victory in Gaul. Pompey hence could not rely on the loyalty of his troops. Instead he decided to move south to the port of Brundisium where he embarked with his troops and sailed east, hoping to raise troops there with which he could return to drive the rebel out of of Italy. His leaving words are said to have been “Sulla did it, why not I ?”

Caesar, with no enemy left to fight in Italy, was in Rome no longer than three months after he had crossed the river Rubicon.

He immediately secured the treasury and then, rather than pursuing Pompey, he turned west to deal with the legions in Spain who were loyal to Pompey.

The campaign in Spain was not a series of battles, but a sequence of skillful manouvers by both sides – during which Caesar, by his own admission, was at times outgeneraled by his opposition. But Caesar remained the winner as within six months most of the Spanish troops had joined his side.

Returning to Rome he became dictator, passed popular laws, and then prepared for the decisive contest in the east, where a large force was now collecting under Pompey.

Pompey also controlled the seas, as most of the fleet had joined with him. Caesar therefore managed only with great difficulty to set across to Epirus with his first army. There he was shut up, unable to manoeuvre, by the much larger army of Pompey. With even more difficulty his lieutenant, Mark Antony, joined him with the second army in the spring of 48 BC.

Some months of manoeuvring following Pompey, though his forces outnumbered Caesar’s, knew well that his eastern soldiers were not to be matched against Caesar’s veterans. Hence he wished to avoid a pitched battle. Many of the senators though, who had fled Italy together with Pompey, scoffed at his indecision and clamoured for battle.

Until at last, in midsummer, Pompey was goaded into delivering an attack on the plain of Pharsalus in Thessaly.

The fight hung long in balance, but eventually ended in the complete rout of Pompey’s army, with immense slaughter. Most of the Romans on Pompey’s side though were persuaded by Caesar’s promises of clemency to surrender once they realized the battle lost.

Pompey himself escaped to the coast, took a ship with a few loyal comrades and made his way to Egypt, where he found awaiting him not the asylum he sought, but the dagger of an assassin commissioned by the Egyptian government.

Caesar in Egypt – The ‘Alexandrian War’

After Caesar’s great victory at Pharsalus, all was not yet won. The Pompeians still controlled the seas, Africa was in their hands and Juba of Numidia was siding with them. Caesar was not yet master of the empire.

Therefore, at the first possible moment, Caesar had set out with a small force after Pompey and, evading the enemy fleets, tracked him all the way to Egypt, where the Egyptian government’s envoys received him, not with his dead rival’s head.

But rather than being able to swiftly move on ad deal with the remaining Pompeians, Caesar became entangled in Egyptian politics. He was asked to help settle a dispute between the young king Ptolemy XII and his fascinating sister Cleopatra.

Though the arrangements Caesar suggested for the dynasty gave such offence to Ptolemy and his ministers that they set the royal army upon him and kept him and his small force blockaded in the palace quarter of Alexandria through the winter of 48/47 BC.

With his force of no more than 3000 men Caesar became involved in desperate rounds of street-fighting against the Ptolemaic royal troops.

Meanwhile, the Pompeians seeing their chance to rid themselves of their foe, used their fleets to prevent any reinforcements reaching him.

Alas, a makeshift force swept together jointly in Cilicia and Syria by a wealthy citizen of Pergamum, known as Mithridates of Pergamum, and by Antipater, a Judaean government minister, managed to land and help Caesar out of Alexandria.

A few days later the ‘Alexandrian War’ was ended in a pitched battle on the Nile delta, in which both the king Ptolemy XII and the true power behind the throne, his chief-minister Achillas, met their death.

The late king’s crown was transferred by Caesar to his younger brother Ptolemy XIII. But the effective ruler of Egypt henceforth was Cleopatra whom Caesar invested a co-regent.

Wether true or not is unclear, but Caesar is said to have spent up to two months with Cleopatra on a holiday tour up the Nile.

Caesar defeats Pharnaces of Pontus

In the summer of 47 BC Caesar began his way home. While passing through Judaea he rewarded the intervention of Antipater at Alexandria with a reduction of the tribute the Jewish people had to pay to Rome.

But more serious matters were still to be taken care of. Pharnaces, the son of Mithridates, had seized his opportunity to recover power in Pontus, whilst the Romans were tied up in their civil war.

In a lightning campaign Caesar shattered the power of Pharnaces. It was at the occasion of that victory on which Caesar dispatched the words back to Rome ‘veni, vidi, vici’ (‘I came, I saw, I conquered’).

Caesar’s final Victory over the Pompeians

By July 47 BC Caesar was back in Rome, and was formally appointed dictator for the second time.

In Spain the legions were in mutiny. And in Africa the Pompeians were scoring victories.

He also found the legions in Campania in mutiny, demanding to be discharged. But what they really wanted was not a discharge, but more pay.

Caesar coolly complied with their demand, granting them their discharge together with a message of his contempt. Whereupon the distraught troops begged to be reinstated again, whatever his terms may be. A triumphant Caesar granted them their will and re-employed them.

Next Caesar carried a force to Africa, but was unable to strike a decisive blow until in February 46 BC he shattered the Pompeian forces at Thapsus. The senatorial leaders either fled to Spain or killed themselves, including Juba, king of Numidia who had sided with them. Numidia in turn was annexed and made a new Roman province.

Caesar returned to Rome and celebrated a series of triumphs. Having reconciliation in mind, he celebrated not his victories over other Romans, but those over the Gauls, Egypt, Pharnaces and Juba.

But more so he astonished the world by declaring a complete amnesty, taking no sort of revenge on any of his past enemies.

Confirmed as dictator for the third time, Caesar occupied himself with reorganizing the imperial system, legislating and planning and starting public works.