The Roman calendar’s approach to leap years was like trying to solve a puzzle with missing pieces, blindfolded, and one hand tied behind their back. Initially, they had a system that was about as reliable as a sundial at night. Enter Julius Caesar, the original calendar influencer, who decided to jazz things up with the Julian calendar, introducing the concept of adding an extra day every four years because, why not? It was their version of hitting refresh on the calendar, except the math was a bit off, leading to too many leap years and holidays that drifted through the seasons like a lost tourist.

Imagine Roman officials scratching their heads, trying to keep track of when to plant crops, or when the next festival was, all while the calendar was doing the time warp. “Wait, is it time to harvest grapes, or are we celebrating Saturnalia this week?” became common questions. And just when you thought you had it figured out, along comes Augustus, tweaking the leap year rules to stop the calendar from sliding into chaos, or at least to ensure his month (August) had just as many days as Julius’s (July).

The leap year solution was like putting a band-aid on a broken chariot wheel—helpful, but you’re still in for a bumpy ride. So, next time February 29th rolls around, raise a glass to the Romans, who tried their best to give us an orderly calendar but ended up giving us an extra day to party every four years instead.

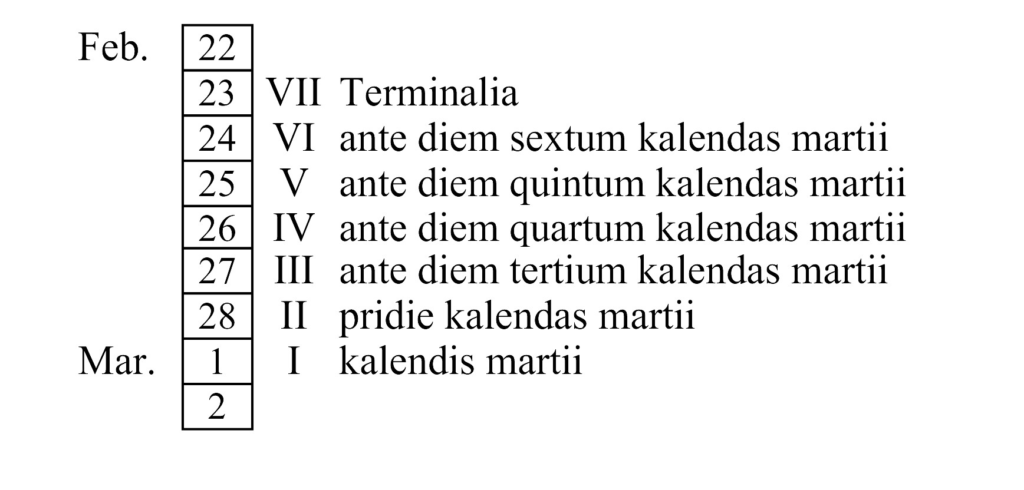

Many argue that historically, the leap day should be February 24, not the 29th. This suggestion is rooted in the original Roman calendar system, which the modern calendar inherits much from, including the names and lengths of months but differs in date identification.

The Romans had a unique way of counting days backward from the start of the next month, a concept similar to modern countdowns for significant events. This backward counting meant that in leap years, an extra day was inserted not at the end of February but as a doubling of February 24 – making it a 48-hour day, technically considered the leap day.

This practice gave rise to the term “bisextile year” found in older texts, with “bis” meaning twice, highlighting the doubled nature of February 24 in leap years. Despite modern calendars showing February 29 as the leap day, strictly speaking, February 24 holds that title historically.

In the late 1990s, Sweden and Finland adjusted their calendars, moving the leap day to February 29 officially, aligning with common practice but diverging from historical precedent. This adjustment even affected the celebration of St. Matthias’s Saint’s day, showcasing the ripple effects of calendar adjustments.

In summary, while modern calendars mark February 29 as the leap day, a deep dive into history reveals that February 24 is the original extra day. Sundial designers and calendar aficionados might note this distinction, perhaps acknowledging the historical leap day in their creations, though the practical impact of this distinction remains minimal for most.