Life: 138-78 BC

Name: Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Early Life

Lucius Cornelius Sulla stemmed from a good, though not very wealthy Roman family. Despite the prestige associated with his patrician lineage, Sulla’s early life wasn’t so easy because of the lack of funds but he displayed adaptability from a young age. It was a promising start to a historic career.

Sulla’s military career began with the Cimbrian War, where he served as a quaestor under the consul Gaius Marius. Sulla proved himself as a competent commander. which led to his advancement through the ranks. which later paved the way for his election to the office of Consul.

He came to prominence most of all in the Jugurthine War and the Social War (91-89 BC). When in 88 BC, Mithridates, King of Pontus, attacked the Roman province of Asia, where an alleged 80.000 Romans and Italians were massacred, the senate decided on Sulla, who was then one of the current consuls, to be commander of the army against Mithridates.

But the Tribune of the People Suplicus Rufus called for the command to be given to Marius. The Concilium plebis backed this proposal. But Sulla proved a man not to be messed with. He marched on Rome at the head of six legions and forced the reversal of this decision.

This type of action was to prove typical of his methods. In a bold maneuver that defied convention, he seized control of Rome through a March on Rome, an act that initiated the city’s first full-fledged civil war. Sulla’s assault on the city in 88 BC was a response to the political challenge posed by his rival, Gaius Marius, and the Marian faction. After his victory, he once again left Rome to continue the war against Mithridates.

Return to Italy

After successfully completing his campaign against Mithridates, he returned back to Italy in 82 BC. Other than having command of a battle-hardened army, he held no office. Sulla was not to wait for anyone to offer him any political position. Far more, he simply marched on Rome and took it by force. The consuls Gnaeus Papirius Carbo and Marius the Younger could not raise an army powerful enough to fend him off. And so Sulla took charge. He was not to take power as an elected consul but in the position of dictator, a post specially set aside in the Roman constitution for times of military crisis.

Becoming a ‘Dictator’

However, everything mentioned above was not a military crisis, and he hardly cared. The position simply allowed him complete power. Once in power, Sulla implemented a series of Reforms and Proscriptions. His reforms were mainly concentrated on restoring the authority of the Roman Senate and reducing the power of popular assemblies and the tribunate. However, it is the proscriptions for which Sulla’s dictatorship is often most remembered.

This meant the publication of lists of any people he deemed undesirable who were considered enemies of the state. Those proscribed were stripped of their property and rights, and it became legal for anyone to kill them without penalty. Rewards would be made to those who brought them in, be they dead or alive. It goes without saying that he used this device in order to annihilate any political opposition rather than to track down any real criminals. Forty senators and 1600 equestrians supposedly died in this first wave of gruesome proscriptions.

Sulla undoubtedly had all the hallmarks of Stalin, Mussolini, or Hitler. He even reveled in calling assemblies at which he would hold grand speeches, threatening and intimidating all those he claimed to be his enemies, as well as his own audience.

Institutional Reforms

Under Sulla’s leadership, the Roman Republic witnessed significant adjustments in its constitutional and institutional landscape. Sulla’s reforms increased the Senate’s power. The magistrates also became more powerful, at the expense of the Tribunes which led to a more traditional balance of power. Sulla’s constitutional reforms set forth a new legislative precedent, often seen as highlighting his autocratic tendencies. These changes reflected Sulla’s vision of the Roman Republic and his belief that without a strong and stable Senate, the would be no stable Rome.

After the damaging conflicts with the Gracchi brothers and their infamous use of other assemblies, the Senate was now reaffirmed as the highest body, entitled to veto any decision reached by another assembly. The power held by the Tribunes of the People was virtually abolished, as they now no longer possessed the power to challenge the Senate. Membership to the Senate was roughly doubled, and many equestrians and magistrates of other cities were added to their ranks.

Further, he introduced a law by which any new member to be admitted to the Senate had at least to have held the position of quaestor beforehand. This was no doubt to ensure the Senate remained a body of political and administrative experience. Also, in order to prevent the re-emergence of serial office holders like the Gracchi, he restored the ten-year waiting period before one could hold the same public office a second time.

In addition to this, perhaps to prevent any meteoric rise to power by people like the Gracchi brothers, he introduced a rule by which anyone holding office would have to wait at least two years before he could be nominated for the next higher office. Of course, such restrictions were to make the struggle for power among the ambitious young sons of powerful families all the more intense. Sulla’s actions included augmenting the number of magistracies assigned to the patricians and limiting the capacities of the plebeians to hold such offices.

Political Relationships and Allies

Lucius Cornelius Sulla’s alliances and rivalries played a pivotal role in shaping Roman politics. His interactions with key figures such as Pompey and Crassus were very important in his rise to power and left a lasting impact on the future of the Republic.

Pompey was one of the most important allies during the dictatorship. Their alliance was grounded in mutual benefit – Pompey could secure military support and prestige, while Sulla reinforced his position within the Senate and among the Optimates, the traditionalist faction. Crassus was another key ally, known for his immense wealth and influence in Rome, with a lot of influence among the Populares.

On the other end, there were Marius and Cinna as the most famous enemies. Marius was the military leader and seven-time consul. He represented a populist challenge to Sulla’s authority.

Their rivalry stemmed from deep ideological differences – Marius was a champion of the Populares, seeking reforms that often ran contrary to the established senatorial order that Sulla aimed to uphold. Cinna, a fellow consul and political ally of Marius, further intensified the conflict. Their opposition escalated into a civil war that would ultimately culminate in Sulla’s march on Rome – a decisive action that demonstrated the sheer influence and ruthlessness he was willing to exert to maintain control of the Republic and assert the primacy of the Optimates. Both Marius and Cinna established proscriptions during their reign while Sulla was away from Rome in wars. Very soon, Sulla fought back.

Dealing with ‘Enemies of the State”

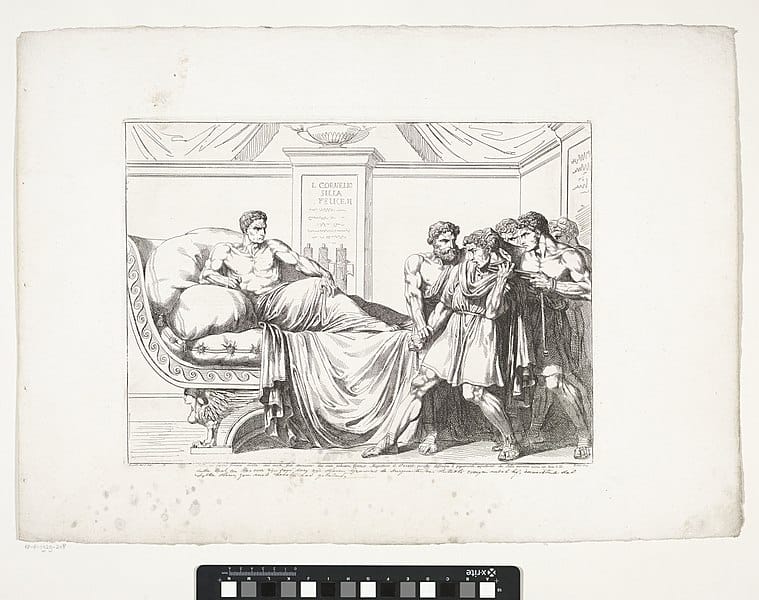

After the names on theenemies list were exhausted, Sulla began adding new names of people who had become ‘enemies of the state.’ There was no place people, once on those lists, were safe. Even those who took refuge in temples were killed. Some might have been hauled before him and thrown at his feet. They were killed nonetheless.

Others fell victim to the mob, being literally lynched by a bloodthirsty crowd. Those suspects who only had all their belongings confiscated and were then thrown out of Rome were indeed the lucky ones among those who felt his wrath, and should any have managed to flee, then an intricate network of spies sought to track them down overseas.

Alas, Sulla was not only to be remembered as a butcher. He also used his position to reform the constitution. Strangely, for a man who himself ignored the Senate’s wishes and who killed an unprecedented number of its members, he did much to restore its authority.

Foreign Policy

Mithridatic Wars

The Mithridatic Wars were a series of three conflicts between the Roman Republic and the Kingdom of Pontus, led by King Mithridates VI. Sulla emerged as a pivotal figure in the First Mithridatic War. His campaign in Athens, although temporarily hindered, eventually succeeded in taking control from Mithridates’ forces, reestablishing Roman dominance.

- Key Battles:

- Battle of Chaeronea (86 BC): A decisive victory for Sulla, demonstrating his tactical acumen.

- Battle of Orchomenus (85 BC): Further solidified Sulla’s reputation and weakened Pontic forces.

Sulla’s impact on the outcome of this war signaled his capabilities as a commander and his influence in setting the military agenda for Rome in the East.

Policies in Asia Minor and Greece

His policies in Asia Minor and Greece were characterized by a balance of military intervention and political strategy. After the First Mithridatic War, Sulla sought to restructure the governance in these regions to secure Rome’s strategic interests and to prevent the re-emergence of hostilities.

- Governance:

- Appointment of Pro-Roman Leaders: Strengthened Rome’s hold on Asia Minor.

- Organizing Asia as a Province: Sulla’s restructuring efforts streamlined Roman administration and increased efficiency.

Sulla’s time as governor of Cilicia and later actions in the region reflected a broader strategy of extending Roman influence through both military might and diplomatic arrangements, ensuring a lasting Roman influence.

The Legal Reforms and Retirement by Sulla

Sulla also instituted legal reforms, which created new courts for particular types of crime. Also, his reforms highlighted between civil and criminal legal procedures. Here, too, the Senate found its authority strengthened, as his reforms allowed only senior senators to sit as judges.

Unusually for a dictator, Sulla retired in 79 BC. He spent his last years on his country estate, writing his memoirs. After he stepped down, he chose to live quietly at his estate in Campania. There, he spent his time in leisure, taking part in activities befitting a Roman patrician of his status. Despite his retirement, his reforms and the precedents he set continued to influence Roman politics. Within a short time, he died of old age.

Legacy

Sulla’s death in 78 BC marked the end of a significant chapter in Roman history. He came from a patrician family and became a central figure in the late Roman Republic.

His legacy survived long after his death. Sulla’s choices, particularly his voluntary retirement, also left a significant imprint on subsequent Roman leaders’ approaches to power and governance.

Under Sulla’s dictatorship, Rome underwent a transformation that was both cultural and social. His constitutional reforms aimed to restore the power of the Senate, largely composed of patricians. This reduced the influence of the plebeians and the Tribune of the Plebs, a critical position often held by commoners. These changes were to ensure a governance model aligning with the traditional Roman values that the patricians represented, reaffirming their social and cultural status in the Roman Republic.

People Also Ask:

What was Sulla known for?

Sulla played an important role in the long political struggle between the optimates and populares factions in Rome. He was a leader of the optimates, which sought to maintain senatorial supremacy against the populist reforms advocated by the popular, headed by Marius.

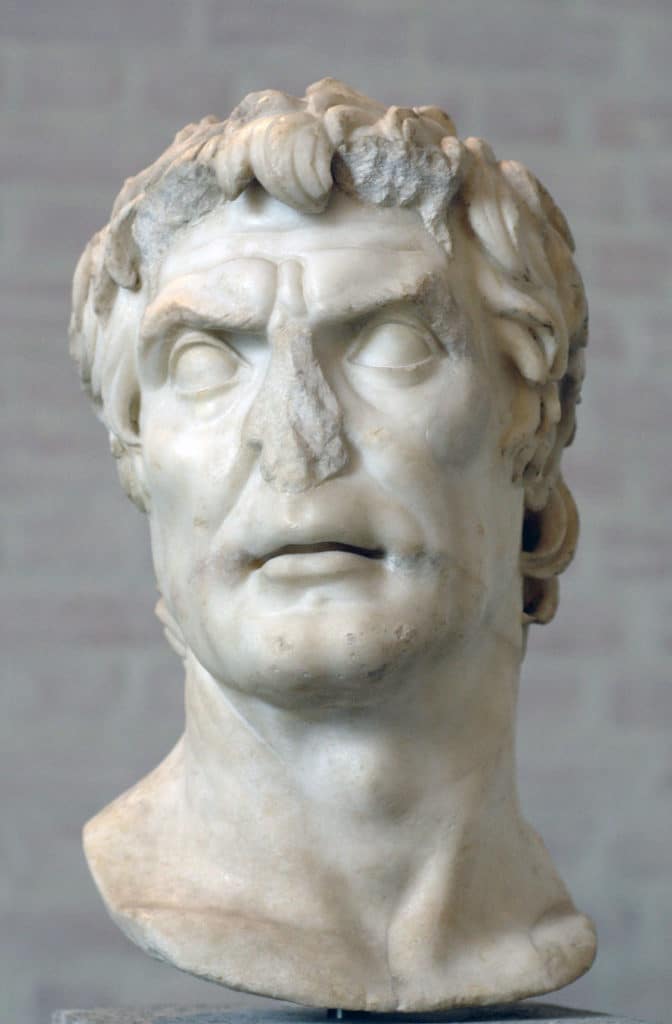

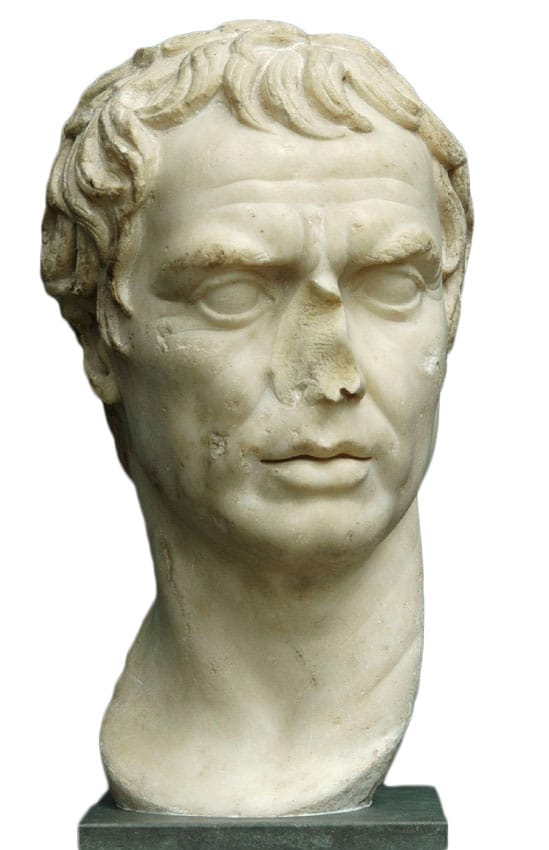

What did Sulla look like?

With his signature golden-red hair and blue eyes, Sulla was by turns charming, vindictive, brilliant, mercurial, and brutal. A patrician of an ancient but impoverished house, he drank hard and went to bed with Roman ladies and Greek actors alike.

What changes did Sulla make to Rome?

Among his other changes to elections, he neutered the plebeian tribunes, turning the office into a dead-end position with little power: their ability to veto public business was removed along with powers to propose legislation. Moreover, anyone elected to the tribunate was thence ineligible for future elected office.

Was Sulla a good Roman leader?

Sulla’s conduct during the war, including a propensity for brutality, established his reputation as a great leader– so much so that he was proclaimed consul of Rome in 88 BCE. Not long after, he would go on to campaign against a formidable enemy at the time, Mithridates Eupator of Pontus.

What did Sulla think of Julius Caesar?

The young Gaius Julius Caesar, as Cinna’s son-in-law, became one of the targets and fled the city. He was saved through the efforts of his relatives, many of whom were his supporters, but Sulla noted in his memoirs that he regretted sparing Caesar’s life because of the young man’s notorious ambition.

Why did Caesar hate Sulla?

Personally, Caesar was certainly not very fond of Sulla. Though he was still a young man during Sulla’s power struggles and civil wars, he was targeted as a political enemy and threat that needed to be removed. Gaius Marius, the seven-time consul and hero of Rome, was Caesar’s uncle.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.