The ancient Roman Empire was a melting pot of diverse cultures, religions, and traditions. The Romans were known for their religious syncretism, which allowed them to absorb and adapt foreign cults and deities into their own pantheon. This cultural exchange gave rise to a vast number of mystery cults and secret societies that flourished throughout the Greco-Roman world.

The study of Roman cults and secret societies is a complex field that requires a multidisciplinary approach. Scholars from various disciplines, such as archaeology, history, anthropology, and religious studies, have contributed to our understanding of these enigmatic organizations. Despite the wealth of information available, many aspects of these cults and societies remain shrouded in mystery, making them all the more intriguing.

Key Takeaways

- Roman cults and secret societies were prevalent throughout the ancient Roman Empire and were characterized by religious syncretism, ritual secrecy, and initiation rites.

- The influence of Roman cults and societies can be seen in various aspects of Roman culture, including art, literature, and architecture.

- The study of Roman cults and secret societies requires a multidisciplinary approach and continues to be a topic of fascination and intrigue for scholars and laypeople alike.

Historical Context and Influence

The Roman Empire and Religious Syncretism

The Roman Empire was a vast and diverse entity that spanned across multiple regions and cultures. As a result, the Roman religion was a mixture of various beliefs and practices from different parts of the empire. This phenomenon is known as religious syncretism, where different religious traditions blend together to form a new, hybrid religion.

The Roman religion was heavily influenced by the Greek religion, which was itself a product of religious syncretism. The Romans adopted many of the Greek gods and goddesses and incorporated them into their own pantheon. The Roman gods and goddesses were often associated with specific roles and responsibilities, such as Jupiter, the god of sky and thunder, and Venus, the goddess of love and beauty.

The Roman cults and religion also had a strong focus on ancestor worship and the veneration of household gods. These gods were believed to protect the family and ensure its prosperity. It also had a complex system of religious rituals and ceremonies, which were performed by priests and other religious officials.

Interactions with Christianity and Judaism

The rise of Christianity and Judaism had a significant impact on the Roman religion. Christianity emerged in the Roman Empire in the early 1st century AD and quickly gained a following. The early Christians faced persecution from the Roman authorities, who saw them as a threat to the stability of the empire.

Despite this persecution, Christianity continued to spread throughout the empire, eventually becoming the dominant religion. The conversion of Emperor Constantine to Christianity in the 4th century marked a turning point in the history of the Roman Empire. Christianity became the official religion of the empire, and the Roman religion began to decline.

Judaism also had a significant impact on the Roman religion. The Jews were a minority in the Roman Empire, but they had a strong influence on the culture and religion of the empire. The Roman religion adopted many Jewish beliefs and practices, such as the concept of monotheism.

The rise of Christianity and Judaism also had an impact on the theology of the Roman religion. The early Christians and Jews challenged the traditional Roman beliefs and practices, leading to a period of theological debate and reform. This period of reform ultimately led to the rise of early Christianity and the decline of the Roman religion.

Major Roman Cults and Mysteries

Mithraism and the Cult of Mithras

Mithraism was a mystery religion that was popular among the Roman military and was centered around the god Mithras. The Roman cult of Mithras was shrouded in secrecy, and little is known about its practices and beliefs. However, it is believed that Mithraism was a male-only religion that emphasized loyalty, courage, and self-discipline.

Mithras was depicted as a bull-slayer. This religion is believed to have originated in the eastern regions, possibly Persia before it spread throughout the Roman Empire.

Source: British Museum, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Mithras was originally an Indo-Iranian deity associated with light, truth, and cosmic order. However, the version of Mithraism that became popular in the Roman Empire was significantly different from its Persian counterpart. This Roman cult began to take shape in the 1st century AD, growing rapidly during the 2nd and 3rd centuries.

The cult had no public ceremonies like the state-sponsored religions of Rome. Instead, its followers gathered in small, exclusive groups in underground temples called mithraea. These temples were often built in caves or were designed to resemble caves, symbolizing the world and the cosmic cave of Mithras.

Central to Mithraism was the myth of Mithras slaying a sacred bull, known as the tauroctony. This act was believed to have cosmic significance, symbolizing the victory of good over evil and the creation of life from the death of the bull. Mithraic rituals likely included reenactments of this myth, along with banquets and initiations that emphasized the bond among the cult members.

Source: Allie Caulfield, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Mithraism reached its peak in the 3rd century AD but began to decline in the 4th century as Christianity gained favor with the Roman state. By the end of the 4th century, Christianity had become the dominant religion of the Empire, and Mithraism, like other pagan religions, was suppressed.

Eleusinian Mysteries of Demeter and Persephone

The Eleusinian Mysteries were a set of initiation rites and ceremonies that were held in honor of the goddesses Demeter and Persephone. The mysteries were held annually in the town of Eleusis and were open to both men and women. The exact nature of the mysteries is not known, as participants were sworn to secrecy. However, it is believed that the mysteries involved a reenactment of the story of Demeter and Persephone and were designed to give participants a sense of spiritual renewal and rebirth.

By the time the Roman Empire absorbed Greece, the Eleusinian Mysteries had already become an established and deeply respected tradition, which the Romans adopted into their own religious practices. The Eleusinian Mysteries took their name from the town of Eleusis, located near Athens. According to myth, Demeter came to Eleusis in search of her daughter Persephone, who had been abducted by Hades, the god of the underworld. The story of Demeter’s grief and her eventual reunion with Persephone became the central narrative of the Mysteries.

Source: Museo nazionale romano di palazzo Altemps, CC BY 2.5 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

The myth symbolizes the cycle of life, death, and rebirth, with Persephone’s descent into the underworld representing the barren winter months and her return to the earth symbolizing the fertile spring. This cycle was seen as a powerful metaphor for the human soul’s journey through life, death, and the afterlife, and the Mysteries promised initiates a deeper understanding of these cosmic truths.

The Eleusinian Mysteries were held annually in two main parts: the Lesser Mysteries and the Greater Mysteries. The Lesser Mysteries, celebrated in the spring, served as a preparatory stage for the main event, the Greater Mysteries, which took place in the fall.

The Greater Mysteries involved a nine-day festival, with the first days dedicated to purification rituals. The initiates, known as mystai, would undergo cleansing rites, including fasting and ritual bathing in the sea. After purification, they participated in a procession from Athens to Eleusis, carrying sacred objects and singing hymns.

The climax of the Mysteries occurred at Eleusis, where the initiates entered the Telesterion, a large hall within the sanctuary, where the most secret and sacred rites were performed. These rites included the reenactment of the myth of Demeter and Persephone, the revelation of sacred objects, and possibly the sharing of a sacramental drink called kykeon. The details of these ceremonies were kept strictly secret, and initiates were sworn to silence about what they witnessed.

The initiation promised spiritual enlightenment and a deeper connection to the divine. It was believed that those who participated in the Eleusinian Mysteries would gain special favor in the afterlife, enjoying a blessed existence rather than the bleak and shadowy fate that awaited most souls in the underworld.

The Eleusinian Mysteries continued to be celebrated well into the late Roman Empire, but they began to decline in the 4th century AD, as Christianity spread and became the state religion. In 392 AD, Emperor Theodosius I officially banned the Mysteries, along with other pagan practices, as part of his efforts to enforce Christian orthodoxy.

The Cult of Isis and Osiris

The Roman cult of Isis and Osiris was a religion that originated in Egypt and was later adopted by the Romans. This Roman cult was centered around the goddess Isis and her consort Osiris, who were believed to be the rulers of the afterlife. The cult of Isis and Osiris was open to both men and women and was particularly popular among the lower classes of Roman society. The cult emphasized the importance of personal salvation and the attainment of eternal life.

The cult of Isis began in Egypt but spread throughout the Hellenistic world following the conquests of Alexander the Great. By the time of the Roman Empire, the worship of Isis had become a well-established religion across the Mediterranean, especially in port cities where her role as a protector of sailors was emphasized.

Source: George E. Koronaios, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The cult of Isis was particularly popular in Rome and across the Roman provinces. Isis was worshiped as a universal goddess who embodied a range of divine roles: she was a mother goddess, a protector, a healer, and a guide to the afterlife. Her worship attracted a diverse following, from slaves and women to merchants and even members of the Roman elite.

The spread of the Isis cult in the Roman Empire was facilitated by its ability to absorb and integrate local traditions and deities. This syncretism made Isis accessible to a wide audience, allowing her cult to thrive in different cultural contexts. In many places, Isis was identified with local goddesses, further broadening her appeal.

Temples dedicated to Isis, known as Isea, were built across the Roman Empire. These temples were centers of religious activity, offering daily rituals, public festivals, and private ceremonies. The rites of Isis included processions, music, and offerings, often involving the use of sacred symbols like the sistrum (a type of musical instrument) and the ankh (a symbol of life).

One of the most important rituals in the Isis cult was the daily awakening of the goddess’s statue, where priests would dress, feed, and worship the statue as if it were the living goddess. Public festivals, such as the Navigium Isidis (the Festival of the Ship of Isis), celebrated her role as a protector of sailors and involved a ceremonial procession to the sea, where a model ship was launched as a symbol of protection and good fortune.

Initiation into the mysteries of Isis involved complex rites that promised a deeper understanding of the divine and the secrets of the afterlife. These rites were shrouded in secrecy, with initiates sworn to silence about what they experienced. The rituals likely involved symbolic death and rebirth, echoing the myth of Osiris, and were believed to ensure the initiate’s salvation and protection in the afterlife.

The cult of Isis was notable for its inclusivity. Unlike many traditional Roman religious practices, which were heavily tied to state and social status, the Isis cult welcomed people from all walks of life, including women, slaves, and foreigners. This broad appeal helped the cult to flourish in a diverse and cosmopolitan Roman Empire.

The Roman cult of Isis remained popular well into the late Roman Empire, but like other pagan religions, it eventually declined as Christianity became the dominant religion. Emperor Theodosius I’s decree in 392 AD, which banned pagan worship, marked the beginning of the end for the public worship of Isis and Osiris.

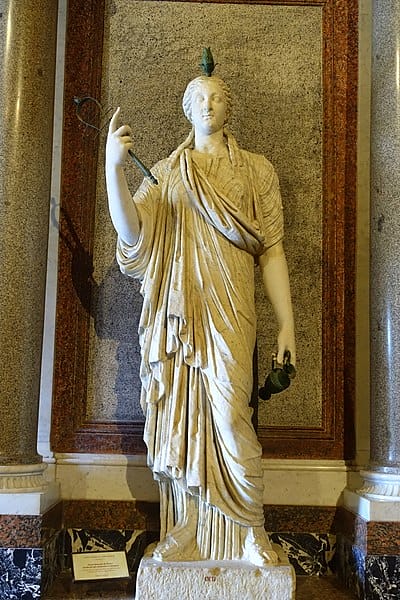

Cybele Cult

The Cybele cult was a mystery religion that was centered around the goddess Cybele, also known as Magna Mater. The cult originated in Asia Minor and was later adopted by the Romans. The Roman cult of Cybele was characterized by its ecstatic rituals, which involved self-mutilation and frenzied dancing. The cult was particularly popular among women and was associated with the god Attis, who was believed to have been castrated and resurrected.

Cybele’s cult was ancient, dating back to the early Bronze Age in Anatolia, where she was revered as a powerful earth goddess. Her worship spread throughout the Hellenistic world, particularly after the conquests of Alexander the Great. The Romans officially adopted Cybele’s cult in 204 BC during the Second Punic War against Hannibal, following a prophecy that Rome would only be saved if the “Great Mother” was brought to the city. The Romans received a black stone, believed to be a manifestation of the goddess, from the Phrygian city of Pessinus, and installed it in a temple on Palatine Hill.

Cybele was depicted as a powerful and majestic figure, often shown wearing a crown with city walls and accompanied by lions, which symbolized her dominion over nature and wild animals. She was also closely associated with fertility, the earth, and mountains.

A central figure in Cybele’s mythology was her consort, Attis, a vegetation god whose myth involved themes of death, rebirth, and resurrection. According to the myth, Attis was a beautiful youth loved by Cybele, but he was driven mad by her and castrated himself under a pine tree, where he died. In some versions, Cybele resurrects him, and this myth of death and rebirth became a crucial aspect of her worship.

A key element of Cybele’s worship was the role of her priests, known as the Galli. The Galli were eunuch priests who had castrated themselves in a frenzied ritual, imitating the myth of Attis. This act of self-mutilation was both a symbol of their devotion and a renunciation of traditional Roman masculinity. The Galli were known for their ecstatic rituals, which included frenzied dancing, drumming, and the playing of cymbals. They often wore women’s clothing and played a prominent role in the public ceremonies of the cult.

Another significant ritual was the Taurobolium, a blood baptism that became more common in the later period of the cult. This rite involved the sacrifice of a bull, with the blood of the animal being poured over the initiate, symbolizing purification, rebirth, and renewal.

The Cybele cult occupied a unique place in Roman society. It was one of the few officially recognized foreign cults and held a special status due to its perceived protective power over the state. Despite its exotic and ecstatic practices, this Roman cult was integrated into the fabric of Roman religious life, particularly among the elite, who sometimes sponsored the expensive rituals associated with the goddess.

Paintings by Andrea Mantegna in the National Gallery, London

Source: Andrea Mantegna, CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The cult of Cybele persisted well into the later Roman Empire, even as Christianity began to rise. The rituals and symbols of Cybele, particularly those related to resurrection and renewal, may have influenced early Christian practices and iconography. The image of the Great Mother and her consort Attis echoed themes that would later be seen in the Virgin Mary and the resurrection of Christ.

Orphic and Dionysian Mysteries

The Orphic and Dionysian M

ysteries were two related mystery religions that were popular in ancient Greece and were later adopted by the Romans. The Orphic Mysteries were centered around the myth of Orpheus, a musician who journeyed to the underworld to rescue his wife. Orpheus was said to have descended into the underworld to retrieve his beloved wife, Eurydice, and his teachings became the foundation for the Orphic tradition. The Orphics believed that Orpheus had received secret knowledge about the gods, the soul, and the afterlife, which he then passed on to his followers.

Source: Giovanni Dall’Orto, Attribution, via Wikimedia Commons

Orphism was deeply concerned with the concept of the soul’s immortality and its journey after death. According to Orphic teachings, the human soul was divine in origin but trapped in a cycle of reincarnation due to past sins. The ultimate goal of the Orphic initiate was to purify the soul through ritual practices and ascetic living, enabling it to escape the cycle of rebirth and return to its divine source.

Orphism also had a unique cosmology and theology, which included a version of the myth of Dionysus Zagreus. In this myth, Dionysus, in his form as Zagreus, was dismembered by the Titans, who were later punished by Zeus. The myth symbolized the fragmentation of the divine soul and its eventual restoration through purification.

Orphic rituals were highly secretive and aimed at purifying the soul. Initiates would follow strict rules, including dietary restrictions, abstinence from certain foods (particularly meat), and other ascetic practices designed to cleanse the soul of its impurities. The rituals also involved recitations of sacred hymns, the use of amulets, and participation in ceremonies that reenacted the death and rebirth of Dionysus.

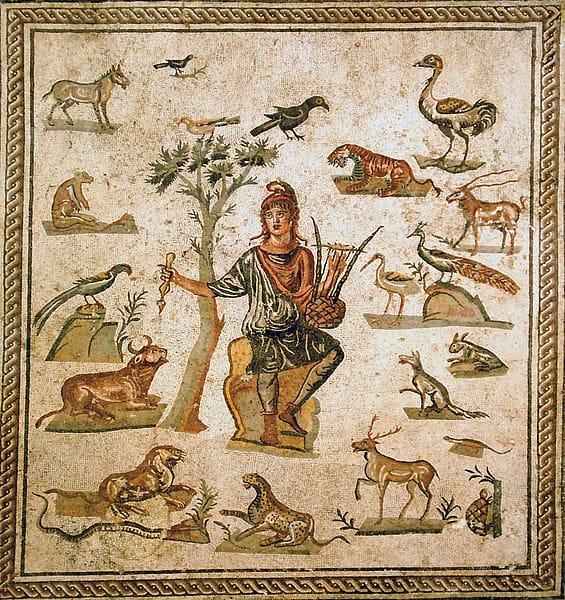

The Dionysian Mysteries were centered around the god Dionysus, who was associated with wine, ecstasy, and fertility. Both cults were characterized by their emphasis on personal salvation and the attainment of spiritual enlightenment.

Source: Tilemahos Efthimiadis from Athens, Greece, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The worship of Dionysus in mystery cults was characterized by ecstatic rituals that sought to bring the worshippers into direct contact with the divine. Dionysus was believed to be a god who could liberate his followers from the constraints of ordinary life, offering them a taste of divine ecstasy and a deeper connection to the natural world. The mythological background of the Dionysian Mysteries included stories of Dionysus’s birth, death, and rebirth, as well as his journey through the underworld. These myths were often interpreted as allegories for the soul’s own journey, with Dionysus serving as a guide and liberator.

The rituals of the Dionysian Mysteries were intense and ecstatic and often involved communal gatherings known as Bacchanalia, named after Bacchus, the Roman name for Dionysus. These festivals featured processions, dancing, music, and the consumption of wine, all of which were believed to bring the participants closer to the god.

The maenads, female followers of Dionysus, played a central role in these rites. They were known for their frenzied dancing and their ability to enter into a state of divine possession, in which they were believed to become one with the god. In this state, the maenads were said to perform extraordinary feats, such as tearing apart animals with their bare hands, an act symbolizing the tearing apart of the boundaries between the human and the divine.

Both the Orphic and Dionysian Mysteries had a significant impact on Roman religious life, particularly among those seeking personal salvation, spiritual enlightenment, and a deeper understanding of the mysteries of life and death. These cults offered an alternative to the formal, state-sponsored religious practices of Rome, providing a more personal and emotionally intense religious experience.

As Christianity became the dominant religion in the Roman Empire, the Orphic and Dionysian Myst

eries, like other pagan cults, gradually declined. However, their influence persisted, particularly in the ways they shaped later religious and philosophical ideas. The themes of death and rebirth, divine ecstasy, and the quest for spiritual liberation continued to resonate in various forms, from early Christian mysticism to Renaissance humanism.

People Also Ask:

What were the main characteristics of the mystery religions in ancient Rome?

The mystery religions in ancient Rome were characterized by their secrecy, exclusivity, and initiation rituals. These religions were often associated with particular gods or goddesses and promised their followers a special relationship with the divine. The mystery religions were also known for their emphasis on personal salvation, which was achieved through participation in the cult’s rituals and mysteries.

Roman cults and secret societies played a significant role in shaping political and social dynamics in ancient Rome. These societies were often made up of elites and were used as a means of networking and establishing connections. They also provided a space for political and philosophical discussions that were not possible in public life. The influence of Roman cults and secret societies can be seen in the careers of many Roman politicians and intellectuals.

What role did initiation rites play in Roman cults?

Initiation rites were an important part of Roman cults. These rites were designed to initiate new members into the cult and were often shrouded in secrecy. The initiation process was meant to be transformative and was often accompanied by symbolic acts such as baptism or the wearing of special clothing. The goal of the initiation process was to create a sense of belonging and to establish a special relationship between the initiate and the cult’s deity.

Can you describe the relationship between early Christianity and Roman cults?

Early Christianity emerged in a cultural context that was heavily influenced by Roman cults. Many of the features of early Christianity, such as its emphasis on personal salvation and its use of initiation rites, can be traced back to these Roman cults. However, Christianity also differed from the mystery cults in important ways. For example, Christianity was more inclusive and had a stronger emphasis on ethical behavior.

What evidence do we have of the practices and beliefs of Roman cults?

The practices and beliefs of Roman cults are primarily known through literary sources, such as the works of the Roman historian Plutarch. Archaeological evidence, such as inscriptions and artifacts, also provides some insight into the practices and beliefs of Roman cults. However, much of what we know about Roman cults remains shrouded in mystery due to their secretive nature.

How did Roman cults and secret societies differ from mainstream Roman religion?

Roman cults and secret societies differed from mainstream Roman religion in several ways. Mainstream Roman religion was characterized by its public nature and its emphasis on the worship of state-sanctioned gods and goddesses. In contrast, Roman cults were often secretive and focused on the worship of particular deities. Secret societies, on the other hand, were not necessarily religious in nature and were often used as a means of networking and establishing connections.

Hello, my name is Vladimir, and I am a part of the Roman-empire writing team.

I am a historian, and history is an integral part of my life.

To be honest, while I was in school, I didn’t like history so how did I end up studying it? Well, for that, I have to thank history-based strategy PC games. Thank you so much, Europa Universalis IV, and thank you, Medieval Total War.

Since games made me fall in love with history, I completed bachelor studies at Filozofski Fakultet Niš, a part of the University of Niš. My bachelor’s thesis was about Julis Caesar. Soon, I completed my master’s studies at the same university.

For years now, I have been working as a teacher in a local elementary school, but my passion for writing isn’t fulfilled, so I decided to pursue that ambition online. There were a few gigs, but most of them were not history-related.

Then I stumbled upon roman-empire.com, and now I am a part of something bigger. No, I am not a part of the ancient Roman Empire but of a creative writing team where I have the freedom to write about whatever I want. Yes, even about Star Wars. Stay tuned for that.

Anyway, I am better at writing about Rome than writing about me. But if you would like to contact me for any reason, you can do it at [email protected]. Except for negative reviews, of course. 😀

Kind regards,

Vladimir