Roman society was sharply divided between the wealthy elite and the poor majority, yet a smaller group occupied a space in between. This segment showed signs of moderate prosperity, though it lacked the status and recognition of the upper orders. Members of this group came from varied backgrounds, including freedmen, skilled workers, merchants, and veterans who had gained stability through service or trade.

Their position was complex, as wealth alone did not guarantee respect. Many traditional elites dismissed their occupations as unworthy, even when those jobs provided comfort and success. Archaeological remains, tomb inscriptions, and household artifacts reveal how these individuals lived, spent, and sought to display their achievements, offering a clearer picture of life beyond the extremes of wealth and poverty.

Key Takeaways

- A small group lived between poverty and elite wealth.

- Occupations and income shaped social standing and respect.

- Freedmen and veterans often moved into this middle position.

Roman Social Hierarchy

Senators, Knights, and City Councilors

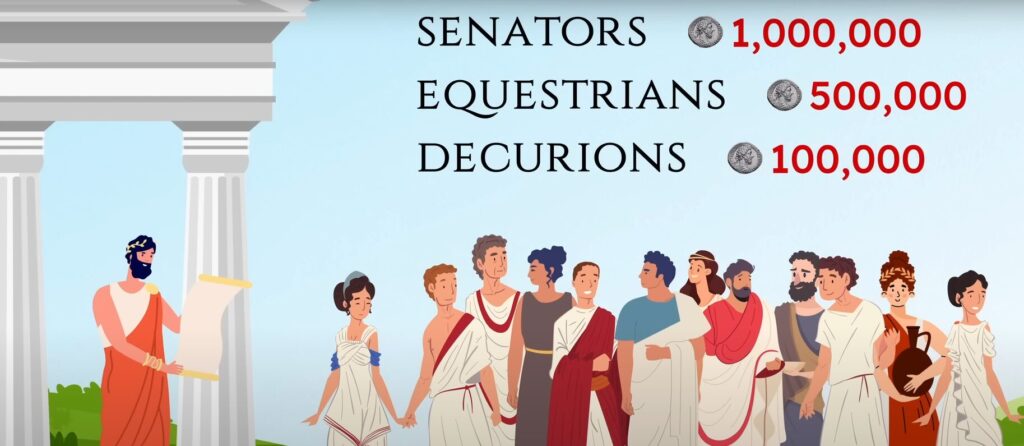

Roman society placed its highest ranks in three official groups: senators, equestrians, and local council members. Each group had wealth requirements:

| Rank | Minimum Wealth Requirement | Role |

|---|---|---|

| Senator | 1,000,000 sesterces | Highest political and social authority |

| Equestrian | 500,000 sesterces | Often engaged in business, military, or administration |

| Decuran (City Councilor) | ~100,000 sesterces (less in small towns) | Governed provincial cities |

Though these groups made up only about 1% of the population, they controlled close to 25% of the empire’s wealth. Their influence extended beyond money, as they also claimed prestige through family heritage, education, and cultural refinement.

Wealth, Status, and Respectability

Members of the elite valued ancestry, education, and taste as much as wealth. Land ownership was considered the most honorable source of income, while trade, manual labor, and entertainment were seen as unworthy of a gentleman. Professions like architecture, medicine, and teaching were acceptable, but only for freedmen, not for those seeking elite status.

At the same time, skilled craftsmen, merchants, and freedmen could build notable fortunes. Examples include:

- Craftsmen working with gold, silver, or gems

- Merchants trading in spices, silk, or popular goods like fish sauce

- Freedmen who ran shops, practiced trades, or partnered with their former masters

Material culture, such as fine pottery, decorated homes, and elaborate tombs, often reflected this prosperity. Yet the boundary between the wealthy sub-elite and the lower aristocracy remained narrow, showing how closely linked money and social ambition were in Roman life.

Defining the Roman Middle Class

Romans of Moderate Means

A small portion of the population lived between wealth and poverty. They were not part of the senatorial, equestrian, or local ruling orders, but they earned more than the majority of poor Romans. Skilled craftsmen, merchants, and freedmen who invested in business could achieve comfortable lives.

Examples include:

- Craftsmen working with gold, silver, or gems

- Merchants trading in spices, silk, or fish sauce

- Freedmen managing shops or workshops after gaining liberty

Archaeological finds such as modest houses, decorated apartments, and fine pottery suggest that these groups had disposable income and access to affordable luxuries.

This group did not see themselves as a unified class. Their occupations and backgrounds varied, and they lacked a common social or political identity. Some lived in modest homes, while others built tombs that highlighted their personal success.

Material culture, such as pottery or household goods, cannot be tied directly to a “middle class.” Instead, evidence points to a broad range of individuals with moderate prosperity but without collective recognition.

Views of the Elite and Social Limits

Members of the aristocracy judged wealth by lineage, education, and land ownership rather than by trade or craft. They considered politics, law, and estate management respectable careers, while most other occupations were seen as unworthy.

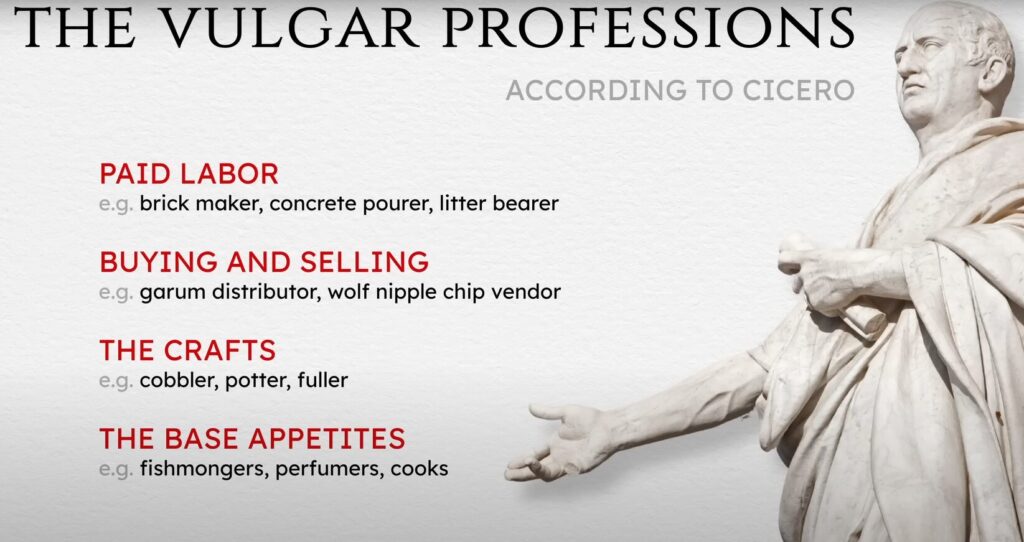

Cicero described many jobs—manual labor, trade, and performance—as vulgar. Even profitable work in crafts or commerce carried stigma. Professions like medicine, teaching, or architecture were more respected, but often viewed as fitting only for freedmen.

Key contrasts:

| Elite Standards | Middle-Class Reality |

|---|---|

| Landed estates as proper income | Trade, craft, and business as main income |

| Politics and rhetoric as noble pursuits | Skilled work and commerce as common paths |

| Respect based on ancestry | Success tied to personal effort and wealth |

These barriers kept many prosperous Romans outside the ranks of the elite, even when their income rivaled that of lower aristocrats.

Work and Social Standing

Respected Lines of Work

Roman elites valued landownership as the most honorable source of income. Political roles and legal advocacy were also seen as proper pursuits for gentlemen. Professions such as architecture, medicine, and teaching carried respect, though these were usually considered suitable only for freedmen.

Negative Views of Trade and Manual Work

Activities linked to buying, selling, or manual labor carried a strong social stigma. Cicero described wage labor as close to slavery and dismissed crafts as unworthy of a freeborn man. Professions tied to entertainment, such as acting or dancing, were ranked among the lowest. Even successful merchants risked losing status if their wealth came from trade.

| Viewed as Respectable | Viewed as Disreputable |

|---|---|

| Landed estates | Wage labor |

| Politics | Retail trade |

| Legal advocacy | Crafts and manual work |

| Architecture, medicine, teaching (for freedmen) | Acting, dancing |

Rising Through Skilled Work

Despite prejudice, skilled trades often provided real opportunities for wealth. Craftsmen working with gold, silver, or gems could achieve prosperity. Merchants dealing in luxury items like silk or spices, or even in goods such as fish sauce, sometimes grew rich enough to rival lower-ranking aristocrats. Freedmen and veterans especially benefited, using their skills, connections, or military rewards to secure financial stability. Some even rose into local leadership, while others passed their gains to children who advanced into higher ranks of society.

Material Culture and Archaeological Evidence

Homes of Pompeii’s Sub-Elite

Archaeological remains in Pompeii show that individuals outside the top aristocratic ranks lived in a range of housing. Some occupied modest private homes such as the Casa del Armasimo, while others lived in larger apartments like the Caucula Equestria in the Insula Ariana Polana.

These spaces varied in size and decoration, but both types have been described as belonging to people of moderate means. The evidence does not allow for a strict division between middle and upper social groups, yet it highlights a visible layer of residents who were neither elite nor poor.

Objects and Everyday Purchases

Finds from Pompeii also include goods that point to disposable income among sub-elite consumers. Items such as aretine ware—a fine red pottery—were common. Glazed ceramics that imitated silver and gold vessels also appear in the record, suggesting demand for items that blended practicality with display.

Archaeologists use these artifacts to trace patterns of consumption. While no single object can be tied directly to a social class, the presence of such goods indicates that a portion of the population could afford more than basic necessities.

Examples of consumer items found in Pompeii:

- Fine red pottery (aretine ware)

- Glazed ceramics imitating precious metal vessels

- Domestic goods showing both function and decorative appeal

This material record shows how people below the elite engaged with markets and expressed status through the things they owned.

Freedmen and Social Mobility

Routes to Wealth

Freedmen often advanced through trades and business ventures. Many had been trained as shopkeepers, artisans, or skilled workers while enslaved, and after manumission they continued in these roles. Their ties to former owners sometimes gave them financial backing or partnerships that freeborn competitors lacked.

Profitable paths included:

- Crafts and skilled labor: working with metals, jewelry, or luxury goods.

- Trade and commerce: managing shops or dealing in products like fish sauce, spices, or textiles.

- Medical practice: some freedmen became doctors and surgeons, investing their earnings in civic life.

These opportunities allowed certain freedmen to accumulate wealth rivaling that of lower-ranking aristocrats.

Freedmen in Roman Writing

Roman authors frequently depicted freedmen as symbols of sudden prosperity. Satirists described characters who owned multiple shops or claimed fortunes in the millions. These portrayals reflected both real success stories and elite disdain for those who rose through commerce rather than lineage.

Examples in literature often exaggerated wealth, but inscriptions confirm that some freedmen openly celebrated their earnings. By recording their achievements on tombs, they demonstrated pride in the financial and social progress they had made.

Tombs and Public Display

Monumental tombs served as lasting markers of status. Freedmen used them to showcase occupations, generosity, and family legacy. Gravestones often displayed images of tools or products connected to their trade, such as shoes for a cobbler or bread for a baker.

Some epitaphs listed the costs of freedom, civic memberships, and public donations. Others highlighted charitable acts or property ownership. These inscriptions and structures acted as status symbols, signaling that freedmen had moved beyond poverty and secured recognition in urban society.

| Example | Occupation | Tomb Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Gaius Julius Helius | Cobbler | Carved shoes |

| Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces | Baker | Reliefs of bread-making |

| Unnamed freedman doctor | Physician | Recorded payments for freedom and civic roles |

Through these displays, freedmen carved out a place for themselves in a society that often judged them by birth rather than achievement.

Veterans as Middle-Class Citizens

Financial Rewards from Service

Roman veterans often entered civilian life with significant resources. Regular soldiers earned wages similar to skilled craftsmen, while officers could make far more. Upon discharge, many received a bonus equal to ten years of pay, either in cash or land. This payout allowed them to establish farms, start businesses, or invest in property.

Forms of Wealth Gained by Veterans

| Source of Income | Example Outcome |

|---|---|

| Regular Pay | Comparable to craftsmen |

| Officer Pay | Up to 50x soldier’s wages |

| Discharge Bonus | Land or 10 years’ wages |

| Post-Service Work | Farming, trade, or crafts |

Veterans in Civic Life

Many veterans became active members of their local communities. Some served as town councilors, while others gained recognition through public monuments and donations. A few were honored with statues or elected to local offices, showing how military service opened doors to civic leadership. Their tombs and buildings often reflected their prosperity and civic pride.

Community Roles Held by Veterans

- Town council members

- Local benefactors through gifts and bribes

- Builders of public monuments

- Honored citizens with statues

Illustrations of Veteran Achievement

Several veterans rose well beyond modest prosperity. One Egyptian veteran owned estates with more than a dozen tenants. Another held properties in multiple villages and maintained influence with officials. In Cologne, the mausoleum of Lucius Publicius still stands as evidence of wealth and status. Some families advanced further: the grandson of one veteran became a senator, showing how military service could lift a family into the elite within two generations.

Not all veterans reached such heights, but many secured stable, comfortable lives as farmers, craftsmen, or merchants, placing them firmly within Rome’s middle ranks.

Routes into High Status and Long-Term Results

Rising Through Society

Movement into the upper ranks of Roman life often came through wealth, connections, or military service. Freedmen could climb by turning skills and business ties into lasting prosperity. Many displayed their success on tombs, marking trades such as cobbling, baking, or medicine with carvings and inscriptions.

Veterans also formed a strong presence in city life. Regular soldiers earned steady pay, while officers left service with large fortunes. Some invested in farming, others in trade, and a few gained local political offices. In rare cases, their descendants entered the senatorial class.

Examples of Advancement

| Group | Pathway to Status | Evidence of Success |

|---|---|---|

| Freedmen | Trade, crafts, partnerships with patrons | Tombs showing wealth, luxury homes |

| Veterans | Land grants, farming, local politics | Large estates, decorated mausoleums |

| Skilled Workers | Crafts and commerce | Prosperity from goods like jewelry, sauces, or textiles |

Wealth Maintained or Lost

For some families, prosperity lasted only a generation or two. A handful managed to cross into the elite, but most remained in the ranks of craftsmen, merchants, or farmers. Veterans who gained land could pass it on, but many descendants slipped back into poverty.

Artifacts such as fine pottery or modest houses show a group with disposable income, but not guaranteed stability. Prosperity depended on steady trade, patronage, or land, and when these failed, families often returned to ordinary lives among the poor.

Patterns of Outcome

- Upward Mobility: A small number reached elite orders.

- Stability: Many lived comfortably but without lasting influence.

- Decline: Others fell back into poverty after brief prosperity.