Roman slaves labored in the mines and in the empire’s many farms and potteries. The state’s public works were largely completed and maintained by slaves. Also, the government’s state bureaucracy depended very much on educated slaves to keep the administration of the empire running. Even key institutions like the state’s mints or the distribution of the corn dole to poor Romans depended on slaves.

Other educated slaves also kept the private industries going, by functioning as their accountants and clerks. Other vital services were provided by literate slaves who served as teachers, librarians, scribes, artists, entertainers – even doctors.

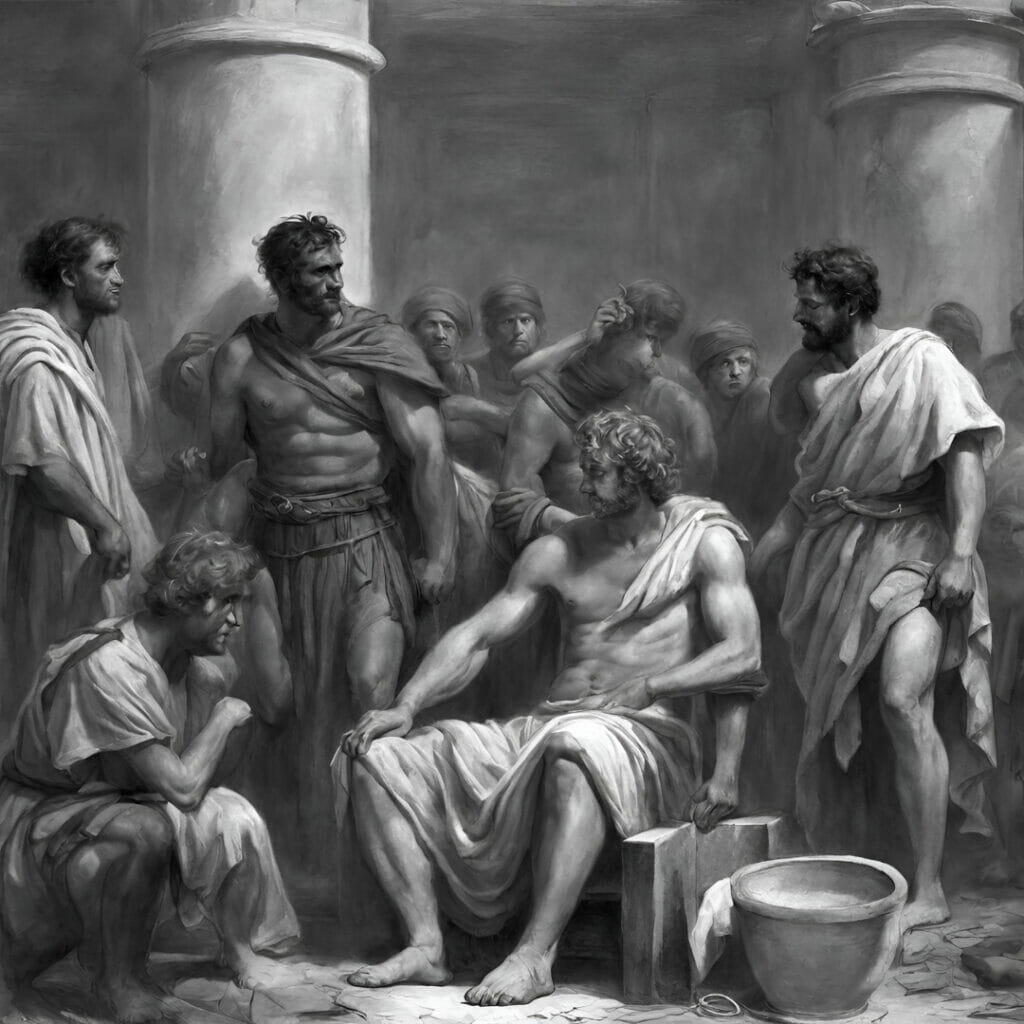

Also in the private houses of Rome, it was slaves who were the servants of their Roman masters, watching over their private lives.

From the man who cleaned the sewers to the emperor’s scribe, slaves were an essential part of Roman society.

In the latter centuries of the Roman empire, slavery began gradually to decrease in importance, as the rise of Christianity demanded more benevolence, and – no less importantly – the supply of slaves began to dwindle.

Roman slaves as symbols of wealth

Had the early Romans been content with a small number of household slaves, these numbers would have risen steeply with Rome’s increasing wealth. Simple tasks, such as the master’s bath, would require the attendance of more than one slave. A slave was used to take the children to school.

In households of the rich where there were many Roman slaves, they were divided into groups of ten, each under the orders of a foreman. The running of the household was in some homes left in the hands of a freed slave, the so-called procurator (in earlier days he was called the atriensis). Even those Romans with very moderate means expected to be well served, taking at least three slaves with them to the baths. Not having one slave was a sign of the most degrading poverty.

Slaves used for industrial purposes were generally divided into gangs. These gangs were closed groups of specialist workers who tended to work as a unit and were generally not split up again.

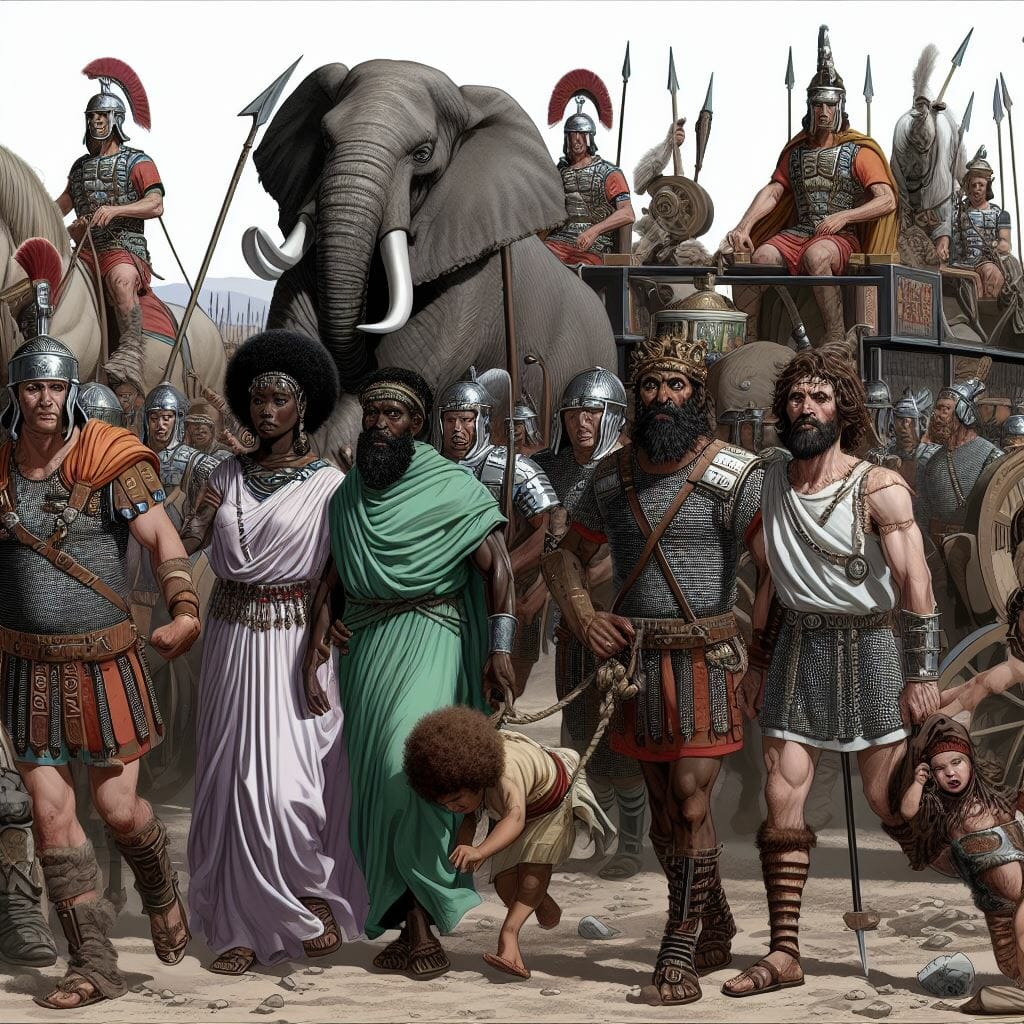

Becoming a Roman slave

Provincial tax collectors, especially those in Asia Minor (Turkey), often acted as suppliers of Roman slaves from the provinces, transporting them to the provincial slave markets from where they would purchased by wholesale buyers who’d most likely ship them back to Rome for sale. One of the largest such wholesale markets was known to be on the island of Delos in the Aegean Sea and possessed a capacity for as many as 10,000 slaves.

The acquiring of slaves through conquest was a common practice among all the civilizations of the ancient world and Rome was no exception. Julius Caesar, having captured a town in Gaul, sold on the spot the entire population of a district of the place to the slave traders who accompanied his army. Once all were counted the slavers walked away with no less than 53,000 people.

Up to the days of Augustus, a marriage between Roman slaves needed not to be recognized by its master and enjoyed no protection in law. The children of such a couple would be born as slaves.

A slave who ran away would face branding or possibly even death. The treatment of Roman slaves was totally in the hands of the owner and usually varied according to their abilities.

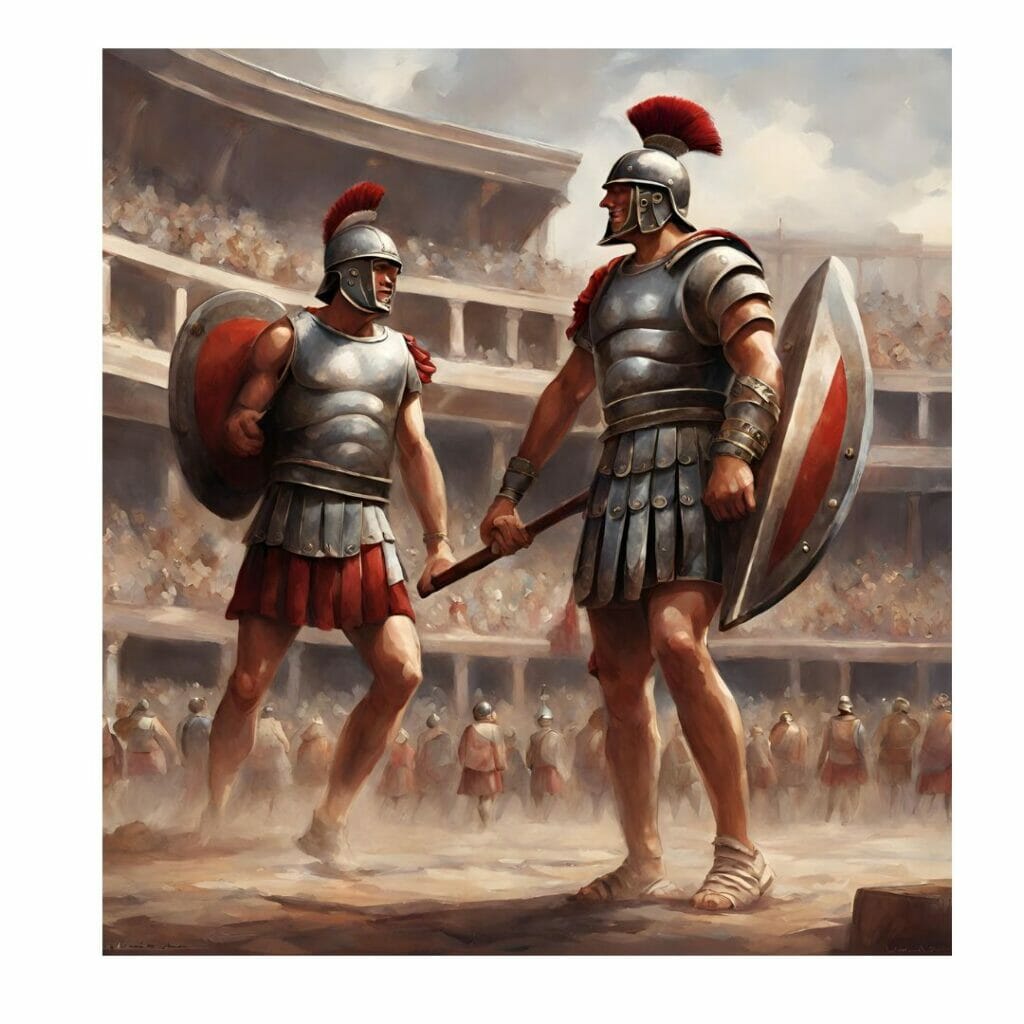

Some among them were trained as skilled fighters to perform as gladiators in the arena. It was at one of those gladiator schools in Capua that the famous revolt of Spartacus arose in 73 BC.

If the gladiators’ lot was cruel, then others too had a pitiful existence. Farm slave gangs would have to work in the fields in chains, and were locked up each night in barracks.

But not all Roman slaves in the countryside necessarily had such a terrible existence. Herdsmen for example, of which there were very many, were granted reasonable independence as they went about their lives, watching over the herds they were entrusted with.

Some Romans would even see the raising of slaves as a form of investment. Cato the Elder bought young slaves whom he would then have trained in various skills, so he could sell them on later at a profit. It was also from Cato’s writings that one knows of his opinion that twelve slaves – a foreman and eleven workers – were deemed sufficient to run a farm of some 150 acres, which would grow olives and rear sheep.

The abundance of slavery is also seen as having hampered technological advances in many industries, not least agriculture. With the existence of so a plentiful supply of labor at almost no cost, there was little reason to develop any form of labor-saving equipment.

Slave markets

Under the supervision of the aediles, the slave dealers sold their wares publicly, either in the open forum or in shops. Roman slaves for sale would sometimes be stood on revolving stands. Those just brought from abroad were put on display with one foot whitened with chalk. From the neck of each slave for sale hung a plaque with all the information required by potential buyers, nationality, abilities, good and bad points, etc.

The best Roman slaves were to be found in the saepta near the forum, the meeting place of the fashionable world, where the best shops were. Naturally, prices varied with the age and quality of the slave.

There are records of fabulous sums being paid, as well as very small prices. One evidently particularly talented teacher of grammar (grammaticus) is supposed to have fetched 700,000 sesterces, a fortune.

But such excessive prices were rare. By general rule, a slave at some skill was worth twelve times as much as an untrained one.

Intelligence and learning were the attributes that elevated the price of a slave the most. Next came good looks and skills in various types of work. But also mentally retarded, dwarfed, or disfigured slaves could fetch high prices from buyers seeking ‘jesters’ for their own cruel amusement.

Freedom

Some Roman slaves could buy their freedom. This principle, which became fairly widespread, consisted of allowing a slave to have a small ‘part-time job’ selling wares or services. The profits would be his to keep (the peculium). And in time he could purchase his freedom. But this system was far from being pure kindheartedness on the part of the owners. Like this an old slave might buy his freedom, allowing his master to buy a new young slave with the money. Hence the master didn’t lose his investment with the slave’s eventual death.

The practice became so popular after the fall of the republic that emperor Augustus saw it necessary to issue laws restricting it. Once freed, a slave enjoyed full citizenship except for the right to hold public office. And some freedmen used their skills, to become richer even than the masters who had once possessed them.

Another privilege a slave might be awarded by his master, apart from the peculium, was the right to choose a mate from among the female slaves and live with her in a form of marriage, the so-called contubernium. This slave marriage though had no legal status and any children born from it belonged as slaves to the master of the house.

In imperial days the contubernium became legally recognized, forbidding any master to sell partners of the contubernium separately.

Hard life of a Roman slave

Roman law regarded slaves as mere chattels. They were subject to the will of their masters, against which they enjoyed no protection.

Punishments inflicted upon slaves were merciless. Hard labor, whippings, branding, breaking of the joints or bones, branding of the forehead with letters denoting the slave as a runaway, liar, or thief (FUG, KAL, FUR) and crucifixion were all punishments that were inflicted upon Roman slaves. So too, being thrown to the wild beasts in the circuses or even being burnt alive in a cloak soaked in pitch.

But in the days of the empire, the unlimited power of the master over his slaves was curbed to some extent. Hadrian decreed that a master should no longer hold power over a slave’s life and death. And Constantine the Great defined the killing of a Roman slave as murder.

Many different stories

However deliberate cruelty against slaves was frowned upon by a society that did recognize slaves as human beings. Romans generally saw the difference between the slave and the freeman as a difference in status, not as a matter of any racial or cultural superiority and inferiority.

Naturally, there are many gruesome tales of abuse and brutal punishments. But in turn, there are also reports of some Roman slaves being utterly devoted to their masters. Some endure horrendous tortures and death rather than betraying their masters.

And yet still the Roman view of slaves was one of contempt. Slaves were people one looked down upon. Kindness toward them was rare, even seen as a sign of weakness.

People also ask:

1. What kind of slaves did Romans have?

One could become a Roman slave by being imprisoned in a battle, captured and sold by pirates, sold from abroad, or even sold by parents.

2. Were there Roman slaves?

Roman free-born citizens could become slaves only if they were captured in wars with foreign armies.

3. How did Roman slaves get freedom?

By escaping, buying freedom, or by the kind hearts of a former master.

4. How did Roman slavery differ from Greek slavery?

Both Greek and Roman slaves had similar status, but Roman slavery was much more organized and lasted much longer.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.