Meeting in Lucca

While Caesar was in Gaul, the situation in Rome was not calming down at all. Pompey was given the task of supplying the city with grain, and Caesar’s opponent Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus was a candidate for consul. Crassus began to work against Pompey, in alliance with Claudius, and Pompey increasingly leaned towards the Senate, and it increasingly seemed that the triumvirate was falling apart.

Caesar realized that he had to actively get involved in the internal politics of the city in order to preserve the triumvirate. With the consent of Cicero, who did not like Claudius’s arrangement with Crassus, Caesar met with Crassus in Ravenna and managed to reconcile the triumvirs at the famous meeting in Lucca in March 56 BC, since Pompey had no other option but to turn to the triumvirate again. This meeting on the division of spheres of interest between the triumvirs that postponed the civil war for a couple of years was completely public, which speaks of how much power the participants in the meeting had in the republic.

There were 200 senators at the meeting because Caesar was sending gifts to many people, so they came to greet him. Of course, these senators wanted to be in the center of events and be on the winning side in those turbulent times. In order to prevent the election of Caesar’s enemy Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus as consul, it was decided that Crassus and Pompey would personally run for consulship for the next year, and that Caesar would receive Gaul under his administration for another five years.

It was immediately decided that Crassus would receive Syria after the consulship to start a war against the Parthians, and Pompey would receive Spain, so that everyone would be approximately equal in strength. No one dared to rebel against the decisions of the meeting in Lucca. The Senate remained silent in fear, as did Cicero. Only Cato rebelled, but he was physically prevented from supporting the candidacy of Domitius Ahenobarbus, and was even wounded during a clash in the city.

Unrest in Rome and the Death of Crassus

After the consulships of Pompey and Crassus in 54 BC, Domitius Ahenobarbus and Appius Claudius, brother of Claudius Pulcher, who was related to Pompey by marriage, were elected. Each subsequent election brought the possibility of new street battles and bloodshed as the republic counted its last days. After the meeting in Lucca, Pompey did not go to his assigned Hispania but remained in Rome in order to be at the center of events and in 54 BC he again took on the task of supplying the city with grain, while Crassus immediately went east to campaign against Parthia.

Although the richest man in Rome, Crassus was considered inferior to his colleagues in the triumvirate, as his victories paled in comparison to the conquests of Pompey and Caesar. That same year, in 54, Pompey’s wife Julia, Caesar’s daughter, died. It was rightly feared that her death marked the beginning of the end of the cooperation between these powerful individuals, and Crassus’ death sealed the breakup of this alliance.

Crassus became governor of Syria, but his primary goal was to attack Parthia, which was thought to be in disarray. At the Battle of the Balicus River, Crassus’ son recklessly charged with a thousand cavalry against the tactically retreating Parthian army. He was soon surrounded and his head found itself on a Parthian spear, and the Roman allies began to change sides.

The rest of the army retreated to Carrhae. Crassus himself died the next day, during the battle when he was lured into negotiations and then captured and executed. The Romans lost 30,000 soldiers. The Triumvirate ceased to exist with Crassus’s death and a struggle for power between Pompey and Caesar was already in sight.

Conflicts Between Pompeians and Caesarians

Caesar had militarily reached Pompey’s fame and was at an advantage, although Pompey had the support of the aristocracy in Rome, he could not act in the right way precisely because of the aristocracy. Caesar had a superior military force, while Pompey had a certain control in Rome itself. Pompey, now in alliance with the Senate, is increasingly mentioned as a person who should accept the function of dictator, which he refused in public, although Cicero claims otherwise. The triumvirate was shaken.

The first move was made by Pompey, demanding the return of the legions he had lent Caesar for an alleged attack on Parthia. Caesar sent the legions, richly rewarded for their service. In 52 BC, Pompey’s supporters wanted Pompey to be consul, while Caesar’s candidacy was hindered by his absence and the uprising in Gaul, although it was unlikely that Caesar would give up his support in the army to re-enter the uncertain political struggle in Rome. Cato demanded the disbandment of Caesar’s army, while in response Curio demanded the same from Pompey. Then Claudius fell victim to an encounter with his old enemy Milo.

During a chance encounter between armed escorts, Milo’s servant wounded Claudius in the back with a spear. In the resulting chaos, Claudius was killed. His supporters brought his body to the Senate, where in the confusion a fire breaks out, destroying the Curia itself. This incident only accelerated the process of granting power to Pompey under the guise of an election for consul without a colleague on the proposal of Bibulus, which Cato also supported.

He took office in March 52 BC. He passed a law against violence and extended his power in Hispania for another five years, while Caesar demanded the same for himself. The most important law he passed was directed against Caesar, prohibiting anyone from running for consul in absentia. He knew that it was too dangerous for Caesar to appear as a private person in Rome. By doing so, Pompey violated the agreement of Lucca.

End of the Triumvirate

In the following years in Rome, the most important issue was the choice of a replacement for Caesar in Gaul, and it was decided that Gaul with Illyricum would be divided into two administrative territories so that the next governor would not have so much power in his hands. In order not to violate the law, the Senate decided not to discuss Caesar’s replacement publicly until the end of Caesar’s term on March 1, 50 BC. Caesar knew that if he relinquished control of the army, he would be at the mercy of Pompey and his followers and that he would likely be executed.

Caesar could only rely on his army, so he awarded the soldiers rewards and increased their salaries, which increasingly won their favor and allowed them to be used in upcoming conflicts. A regrouping of forces occurred, with Pompey’s side including most of the aristocracy and the entire Senate, including Cicero, on Caesar’s side, while Mark Antony and Curio, whom Caesar had freed from debt, were on Caesar’s side.

Caesar’s proposal, sent through Curio, was to strip him and Pompey of their armies and have them contest politically for magistracies before the citizens of Rome. This was illegal, since Pompey had legally extended his empire in Hispania for another five years. The proposals were put to the vote in such a way that it was possible to reject Caesar and grant Pompey power. Caesar’s proposal was rejected, and Caesar’s men began to threaten with violence.

From Ravenna, where he was lobbying for his candidates in the elections for 49, Caesar sent a more moderate proposal through Curio. He asked that he be left with two legions and a part of Gaul that is now in northern Italy before Caesar could run for consul. Cicero tried to reconcile the two warring triumvirs on the basis of this proposal, while Mark Antony insisted that the legions recruited by Pompey be sent to the East as soon as possible. Pompey eventually accepted that Caesar should have two legions left, but his supporters dissuaded him from accepting the proposal, which Caesar had resubmitted through Curio.

At a meeting in Pompey’s house, despite Cicero’s conciliatory tone, the radical side of the optimates, led by Cato, prevailed, demanding decisive action against Caesar. Moreover, the consul for the year 50, Lentulus, expelled Antony and Curio from the Senate, who had tried to prevent the Senate’s decision that Caesar alone must disband the army or become an enemy of the people. 10.01. 49. BC, Curio and Antony, fearing for their lives, fled Rome and went to Caesar in Ravenna, after which there were no more Caesar’s supporters in the Senate.

It was clear that Caesar gave up trying to negotiate, although both he and Pompey were interested in a certain compromise, unlike their entourage. Caesar’s goal was to come to power, which he wanted to achieve peacefully, but unlike Pompey, he did not rule out civil war, and Caesar made the first move. The Senate gave Caesar the choice between war and humiliation, and Caesar chose war. The triumvirate was dead.

Sources and Literature:

Appianus, of Alexandria. (1902). Appianou Romaikon Emphylion A = Appian, Civil Wars, book I. Oxford: Clarendon Press,

The Cambridge Ancient History IX (2008),

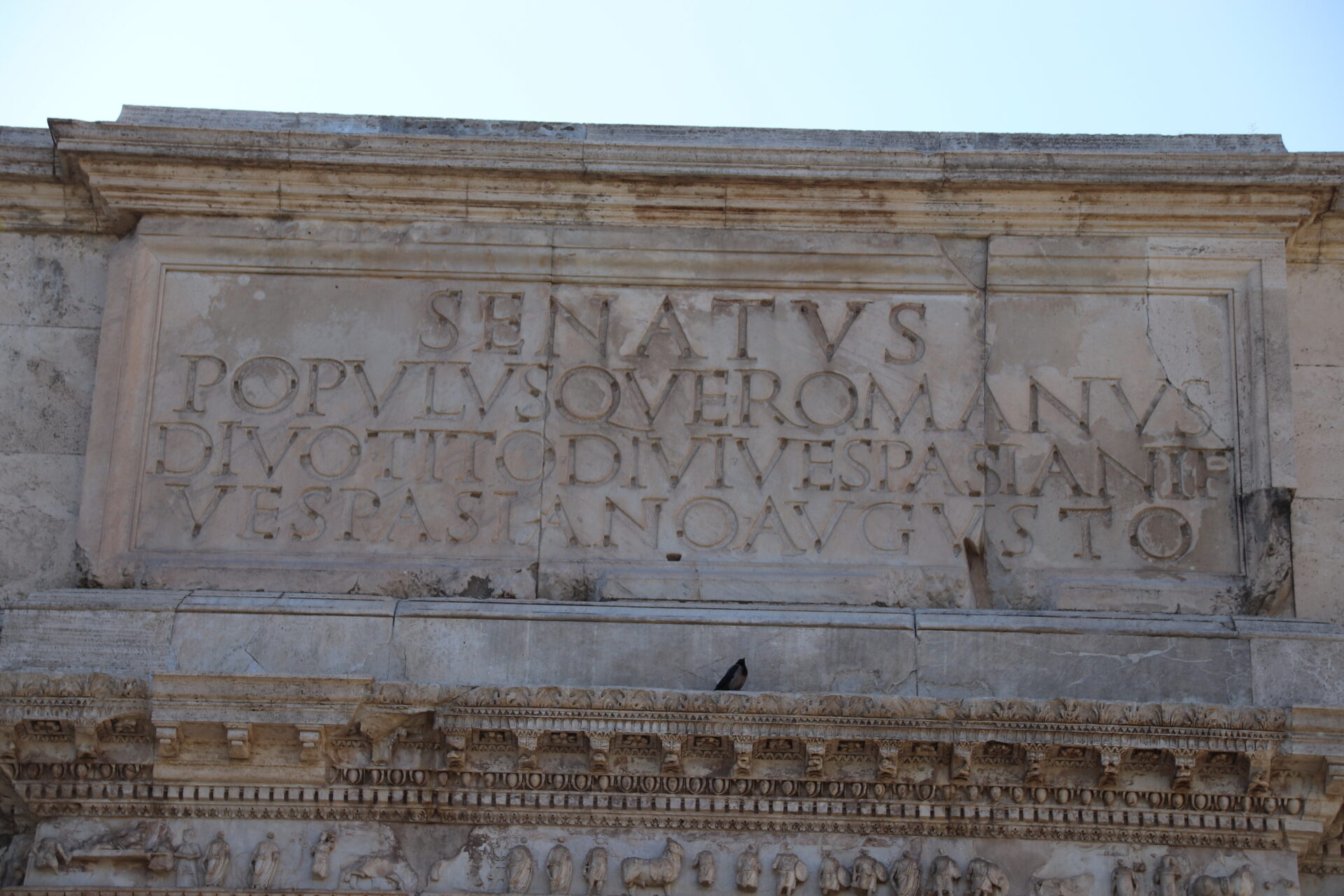

Beard, M. (2015). SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome.

Caesar, Julius. (1953). War commentaries: De bello Gallico and De bello civili. London: New York: Dent; Dutton,

Plutarch. (1859). Plutarch’s Lives: translated from the original Greek, with notes, critical and historical, and life of Plutarch. New York: Derby & Jackson,

Hello, my name is Vladimir, and I am a part of the Roman-empire writing team.

I am a historian, and history is an integral part of my life.

To be honest, while I was in school, I didn’t like history so how did I end up studying it? Well, for that, I have to thank history-based strategy PC games. Thank you so much, Europa Universalis IV, and thank you, Medieval Total War.

Since games made me fall in love with history, I completed bachelor studies at Filozofski Fakultet Niš, a part of the University of Niš. My bachelor’s thesis was about Julis Caesar. Soon, I completed my master’s studies at the same university.

For years now, I have been working as a teacher in a local elementary school, but my passion for writing isn’t fulfilled, so I decided to pursue that ambition online. There were a few gigs, but most of them were not history-related.

Then I stumbled upon roman-empire.com, and now I am a part of something bigger. No, I am not a part of the ancient Roman Empire but of a creative writing team where I have the freedom to write about whatever I want. Yes, even about Star Wars. Stay tuned for that.

Anyway, I am better at writing about Rome than writing about me. But if you would like to contact me for any reason, you can do it at contact@roman-empire.net. Except for negative reviews, of course. 😀

Kind regards,

Vladimir