This series of articles will try to explain the reasons for the fall of the Roman Republic and the establishment of the Roman Empire. It will use respectable sources and literature and will be published weekly.

Roman Republic – Basics

The Roman Republic was created as a way of defending the Roman people from the tyrants and as such lasted for almost five hundred years. Certain institutions that had emerged during the reign of kings survived and were adapted to the republican system, while new institutions and functions were created to make it easier to govern the state and the population.

The most important institution of the republic was the Senate, whose power was correlated with the power of the republic, and once the power of the Senate disappeared, the republic gave way to the monarchy. Since its founding, the Roman Republic had expanded its territory through conquest until it became the dominant power in the known world, but its too rapid expansion led to a period of social and later political crises.

The main problem of the late republic was the failed attempt at an agrarian reform that would satisfy the masses of peasants and veterans. Actually, the problem was the opposition to the reforms by the aristocracy. It ended in bloodshed, with reformers often killed in street battles. Still, the military reforms were even more disastrous for the survival of the republic. The military reforms implemented by Gaius Marius led to the emergence of powerful individuals, as legionaries expressed their allegiance to their commander, not to the Senate.

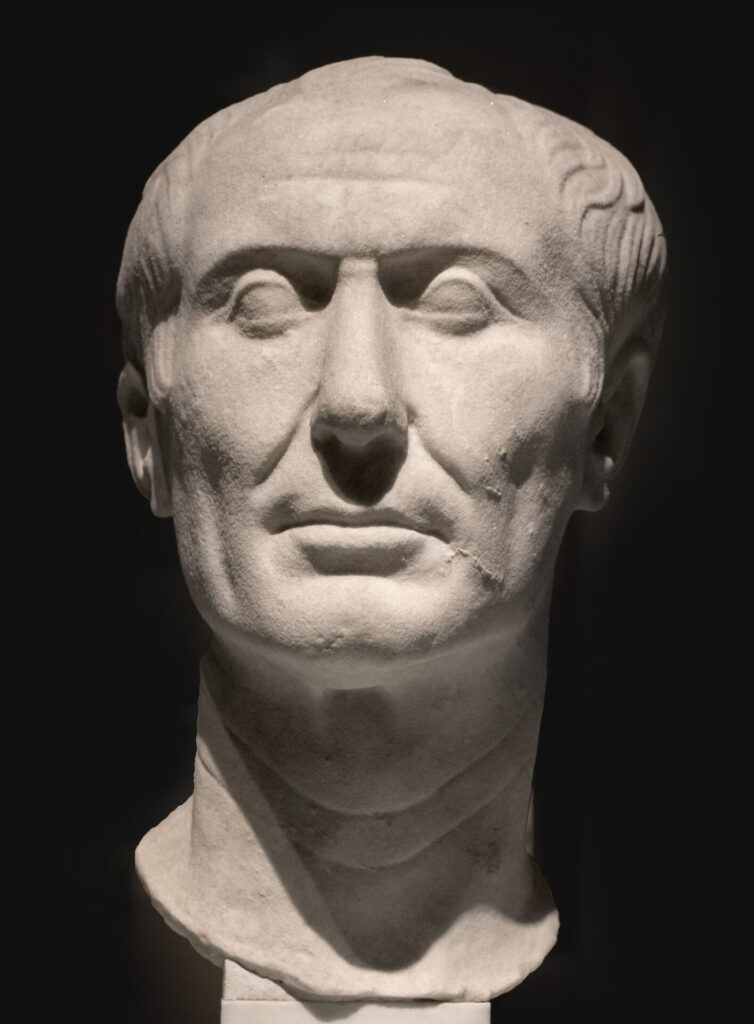

The existence of more than one powerful individual led to civil war, but Sulla’s thinking as a victor was still within the framework of republican understandings. After Sulla’s rule, Gaius Julius Caesar dealt a fatal blow to the Senate and the republic, although he himself did not see the consequences of his actions.

Caesar against the Republic

Caesar respected the institutions and rules of the republic until he was strong enough to reject them and come to power in the way he wanted. By creating the triumvirate and his behavior after the alliance, Caesar made it clear to the Senate and political opponents that he had no problem exceeding the powers he had as a holder of offices within the republic. After the conquest of Gaul, Caesar became powerful and wealthy enough to engage in the final struggle for supreme power over the state.

As the winner of the civil war, Caesar still retained the institutions of the republic and tried to implement his power into a republican system, but he overestimated his own power in the city in a very uncertain period of the development of the Roman state. Caesar was elevated to a pedestal of power by the army, and his pride and the absence of that army cost him his life. The republican system did not survive Caesar’s legal heir Octavian, who continued his path and officially changed the structure of the Roman state.

Sources

We learn most about the turmoil in the Roman Republic from Appian’s Civil Wars, which is considered the primary scholarly work of the period. His Roman History covers the period from the founding of the city to the time of Emperor Trajan, but only those that describe the period of civil wars, more precisely the period from 133 to 31 BC, have been preserved in their entirety.

Appian described people based on when they came into contact with the Roman state so his work is a continuous story about the people being described at that moment. Appian knows how to distinguish important events from anecdotes so he sticks to the main currents of history.

Unlike Appian, Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus writes mostly about anecdotes from the lives of the emperors he writes about. His, The Lives of 12 Caesars, presents biographies of the 12 Roman rulers, including Caesar, are the only source for little-known details of Caesar’s private life. Unfortunately, Suetonius’ work lacks a critical approach to the sources and contains unverified information, although the imperial archives to which Suetonius had access were used as a source.

A biography of Caesar can also be found in Plutarch’s Parallel Lives. Although the beginning of Caesar’s biography is lost, Plutarch is very important as one of the four most important sources for the life of Julius Caesar. Plutarch describes in detail Caesar’s military campaigns and victories in battles, as well as his ability to inspire his soldiers.

Julius Caesar himself is a primary source, as he described in detail the conquest of Gaul in his Commentaries, as well as the reasons for the civil war and the course of the war itself. Caesar’s works must be viewed with special attention because, as a participant in the events he describes, Caesar sometimes overemphasized his role and forgot to write about the events that did not go to his advantage. Despite their shortcomings, the Commentaries on the Gallic and Civil Wars are considered the best sources of Caesar’s military campaigns.

Roman Republic

The Beginning

The Roman Republic was founded in 509 BC to put an end to the tyranny of the last Roman king, Tarquinius Superbus, and his family. Namely, Tarquinius executed many members of the Senate and ordered the construction of large buildings, while exploiting the plebs. The line of tolerance was crossed when the king’s son, Sextus Tarquinius, forcibly used Lucretia, the wife of one of the most eminent citizens of Rome, Tarquinius Collatinus.

Then a group of his conspirators, led by Lucius Junius Brutus, swore to avenge Lucretia and fight against Lucius Tarquinius Superbus and all his descendants. The conspirators quickly gained the favor of the people, so that the Tarquin family was exiled, and the victors against the king, Lucius Junius Brutus and Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, were proclaimed consuls, which practically abolished the kingdom.

Institutions

In order to prevent the entire power in the city from being in the hands of one man, it was decided that the royal power would always belong to two consuls elected by the people, where one consul was to represent a counterweight to the other. Unlike the king, the consular power was limited to one year. Although the consuls were considered a substitute for the royal power, they did not have anywhere near the same power to govern the state as the kings.

The most important right of the kings that was denied to the consuls was the right to manage the finances, which was held by two praetors who were also elected by the people. The first consuls elected new senators to replace those executed by the last king so that the Senate again had three hundred members.

The Roman people feared that in the future the consuls would not have sufficient authority to face external threats, so the possibility of electing a dictator as a kind of temporary king was left open. The dictator was elected in emergency situations and only for a period of six months and had to be a former consul.

The first dictator was elected during the war with the Sabines and is believed to have been Titus Larcius. The appointment of a dictator was ordered by the Senate to the consuls, who were obliged to choose a person to perform this duty. Roman dictators of the early republic should be distinguished from dictators of later periods since Roman dictators were legally elected magistrates.

All these magistracies belonged exclusively to the patricians. The patricians were descendants of old families from the time of the founding of the city and were the only ones who could be elected to the Senate, which took care of the foreign policy of the republic. The patricians represented the aristocratic class. In addition to the patricians, over time a class of plebeians emerged in Rome that had no share in government.

The plebeians immigrated as refugees from other cities or were brought during conquests. They had the right to private property, but they did not have any political rights, nor the possibility of marriage with the patrician class. The plebeians were more numerous and some of them, as they became increasingly wealthy, wanted political equality with the patricians. After the expulsion of the kings, the two classes turned against each other again.

In 494 BC, Titus Livius explains that the plebeians refused to go on a campaign against the Aequi. Negotiations re-established unity in the state so that the plebeians received their own representatives in government every year. These plebeian protectors were called the people’s tribunes and had the task of protecting the plebeians from the tyranny of the patricians.

The tribunes were considered inviolable and had the right to supervise all other magistrates, except the dictator, and to overturn any legislative proposals of other magistrates. Both tribunes were accompanied by assistants called aediles, who were also elected from the ranks of the plebeians. Over time, the distinctions between these two classes were lost, so that plebeians could be elected to all magistracies, and could also be members of the Senate.

The Senate, even in the time of the kings, was a kind of council of elders in Rome. The Senate had an advisory role and was not able to influence the decisions of the kings. During the early republic, the Senate was not yet a strong institution that could impose its will on the consuls. Initially, the consul elected senators whose appointment was for life.

Over time, the Senate became the highest institution of the Roman Republic and had the ability to control the magistrates and vote on the movements of the troops. Foreign policy was the domain of the Senate. The strength of the Senate also represented the strength of the republic, because as long as the senators, who were themselves mostly former magistrates, had control over the magistrates, the republic was stable. The weakening of the Senate opened the way for the era of powerful individuals and paved the way for the re-establishment of the monarchy.

Sources and Literature:

Suetonius, approximately 69-approximately 122. (1883). The lives of the twelve Caesars. New York: R. Worthington,

Appianus, of Alexandria. (1902). Appianou Romaikon Emphylion A = Appian, Civil Wars, book I. Oxford: Clarendon Press,

Plutarch. (1859). Plutarch’s Lives: translated from the original Greek, with notes, critical and historical, and life of Plutarch. New York: Derby & Jackson,

Caesar, Julius. (1953). War commentaries: De bello Gallico and De bello civili. London: New York: Dent; Dutton,

Livy. (1971). The early history of Rome. Books I-V of The history of Rome from its foundation. [Harmondsworth, Eng.]: Penguin,

Morey, W. C. (1900). Outlines of Roman history: For the Use of High Schools and Academies.

Hello, my name is Vladimir, and I am a part of the Roman-empire writing team.

I am a historian, and history is an integral part of my life.

To be honest, while I was in school, I didn’t like history so how did I end up studying it? Well, for that, I have to thank history-based strategy PC games. Thank you so much, Europa Universalis IV, and thank you, Medieval Total War.

Since games made me fall in love with history, I completed bachelor studies at Filozofski Fakultet Niš, a part of the University of Niš. My bachelor’s thesis was about Julis Caesar. Soon, I completed my master’s studies at the same university.

For years now, I have been working as a teacher in a local elementary school, but my passion for writing isn’t fulfilled, so I decided to pursue that ambition online. There were a few gigs, but most of them were not history-related.

Then I stumbled upon roman-empire.com, and now I am a part of something bigger. No, I am not a part of the ancient Roman Empire but of a creative writing team where I have the freedom to write about whatever I want. Yes, even about Star Wars. Stay tuned for that.

Anyway, I am better at writing about Rome than writing about me. But if you would like to contact me for any reason, you can do it at contact@roman-empire.net. Except for negative reviews, of course. 😀

Kind regards,

Vladimir