Introducion

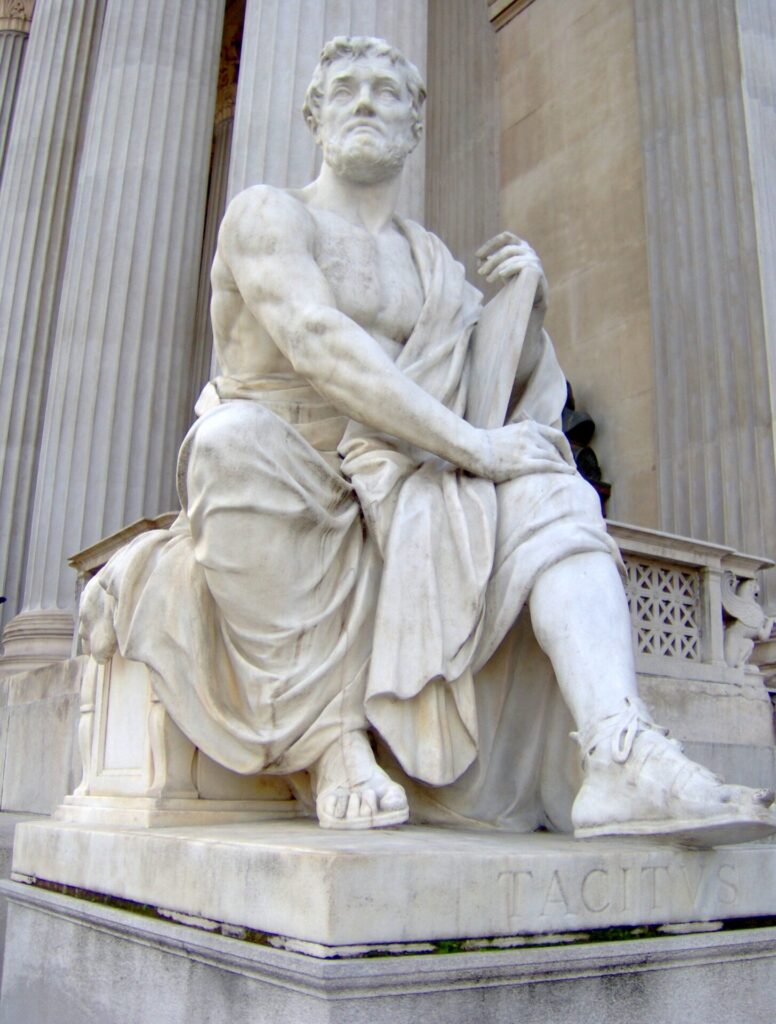

Publius Cornelius Tacitus stands among the greatest Roman historians. A man of letters, law, and politics, Tacitus was not just chronicling events—he was dissecting the soul of Rome. Living during an age of autocrats and brutal political games, Tacitus left behind a body of work that remains essential reading for anyone interested in how empires function and falter. His skepticism toward power, mastery of prose, and psychological insight make him not only a historian but a timeless critic of tyranny. In an era where truth was dangerous, Tacitus wrote history as a form of resistance.

Life and Times of Tacitus

Tacitus was born around 55 AD, possibly in northern Italy or southern Gaul. His family was of equestrian rank, placing him in the privileged but not aristocratic class of Roman society. Like many young Romans of means, he received a rigorous education in rhetoric, literature, and law—tools that would define his later career.

He rose through the Roman political system during the rule of the Flavian dynasty. Tacitus served in various offices of the cursus honorum, the formal sequence of public offices held by aspiring politicians. Under Emperor Domitian, he held posts as quaestor and praetor, and in 97 AD, he was appointed consul suffectus, the highest office of the Republic and an indicator of his prestige. Around this time, he married the daughter of Gnaeus Julius Agricola, a respected Roman general and provincial governor—an alliance that would later inspire one of his earliest works.

Tacitus lived through the tumultuous aftermath of Nero’s death, the rapid succession of emperors in 69 AD (the Year of the Four Emperors), and the stabilization under the Flavians. These events shaped his historical consciousness. His political career flourished even under the shadow of Domitian’s autocracy, but his writings suggest a deeply critical attitude toward the imperial system and the fear it instilled in Rome’s elite.

Major Works

Tacitus’s surviving works cover a broad range of topics, genres, and periods. Though much of his writing is lost, what remains cements his reputation as one of Rome’s most perceptive observers.

Agricola, published around 98, is a biography of his father-in-law. On the surface, it is a celebration of Agricola’s military achievements in Britain. Beneath that, however, it subtly critiques the oppressive reign of Domitian, suggesting that even virtue could become a political liability under a tyrant.

Germania, likely written in the same period, is an ethnographic study of the Germanic tribes beyond the Rhine. Tacitus contrasts their simplicity, martial valor, and communal values with what he sees as Rome’s decadence. It is both a political statement and a historical curiosity, often used (misguidedly) in later centuries by nationalist ideologies.

Dialogus de Oratoribus, or Dialogue on Orators, explores the decline of oratory in the Roman Empire. Through a Platonic-style conversation, Tacitus examines whether the loss of rhetorical brilliance is due to cultural changes or political repression. It offers a fascinating look into the intellectual climate of imperial Rome.

Histories and Annals form the backbone of Tacitus’s legacy. Histories, of which only the first few books survive, cover the turbulent period from 69 to 96, focusing on civil war and the Flavian dynasty. Annals picks up earlier in time, examining the Julio-Claudian emperors from the death of Augustus to the reign of Nero. These works are incomplete, but together they provide an extraordinary political and psychological account of the Roman imperial system.

Style, Method, and Historical Approach

Tacitus’s style is unmistakable—dense, sharp, and often grim. His prose is known for its conciseness, a quality often referred to as “Tacitean brevity.” He writes with irony and subtlety, embedding judgments in word choice and syntax rather than direct statements.

He is not a modern historian in the sense of critical, source-based reconstruction. He often inserted speeches, a common literary convention inherited from Thucydides and Livy. Still, Tacitus demonstrates a deep concern for truth and moral clarity. He often compares sources, weighs possibilities, and questions official narratives, reflecting his belief that history must resist political distortion.

Tacitus was particularly interested in character—how individuals respond to power, pressure, and moral compromise. His histories are filled with portraits that reveal not just what emperors did, but how their personalities influenced Rome’s fate.

Power, Corruption, and the Fragility of Liberty

Tacitus returns again and again to the theme of liberty lost. The early Roman Republic had celebrated civic virtue and public debate, but under the emperors, that tradition was hollowed out. Tacitus presents imperial Rome as a state where surveillance, betrayal, and fear replaced genuine public life.

His works examine how individuals—senators, generals, philosophers—cope with autocracy. Some resist and are crushed. Others adapt, survive, or collaborate. The most chilling aspect of his work is how power deforms not only the ruler but the ruled.

He warns of “the corruption of the best,” where even virtuous men become complicit in tyranny for the sake of comfort or safety. Tacitus does not offer easy heroes, but he mourns the loss of civic courage.

Tacitus and the Emperors: Character Studies of Power

The emperors in Tacitus’s works are not caricatures; they are complex studies in power.

Tiberius emerges as enigmatic and dangerous, initially competent but increasingly withdrawn and sinister. Tacitus’s portrait suggests a ruler who manipulates the Senate while cloaking his intentions in ambiguity.

Caligula and Nero are seen as embodiments of unchecked indulgence and cruelty. Tacitus does not dwell on scandal for its own sake but uses their reigns to show how institutions collapse when fear replaces reason.

In Histories, the chaos of 69—when Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian contended for power—serves as a warning about the fragility of empire. Each leader reveals different forms of weakness and ambition.

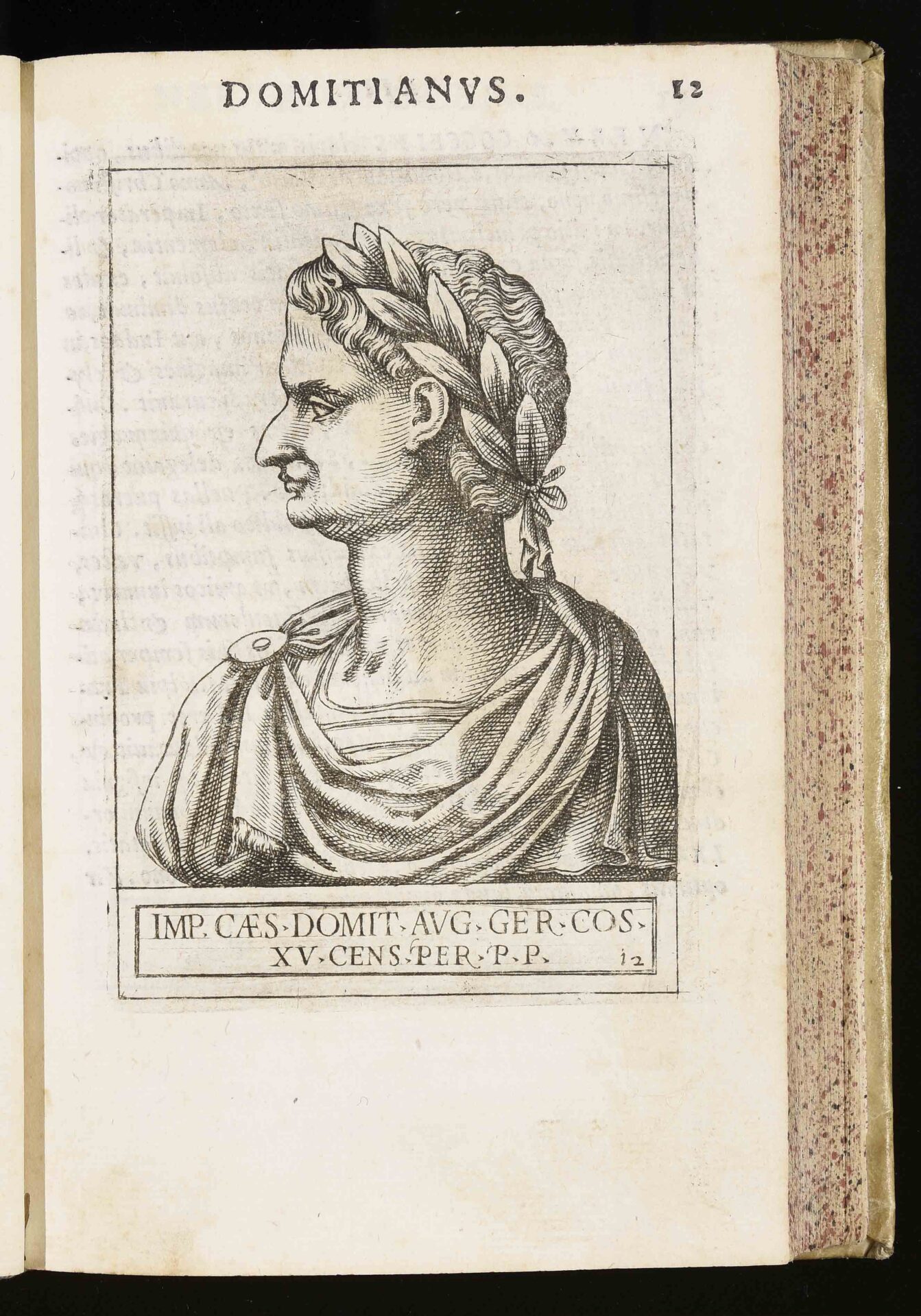

Vespasian and Titus are treated more favorably as stabilizers, but Tacitus never forgets the cost of authoritarian control. Domitian, in contrast, is depicted as paranoid and oppressive, a stark example of tyranny unchecked.

Reception, Influence and Modern Importance

Tacitus’s works survived the Middle Ages in limited form, but during the Renaissance, he was rediscovered with awe. Humanist scholars admired his Latin style, while political thinkers turned to him for insight into power and governance.

Machiavelli cited Tacitus in his Discourses, appreciating his realistic take on politics. In the 18th century, Enlightenment thinkers like Montesquieu and Voltaire read Tacitus as a guide to understanding despotism. His warnings about tyranny and moral collapse resonated deeply in an age wrestling with monarchy and revolution.

Modern historians and writers continue to find relevance in Tacitus. His ability to expose the dark mechanisms of politics has made him a touchstone for analyses of dictatorship, propaganda, and institutional decay. Scholars debate his objectivity, but few question his impact.

His name has even entered political vocabulary: “Tacitean silence” describes public silence under coercion, and “Tacitean cynicism” refers to skepticism about political virtue.

The Enduring Shadow OF Tacitus

Tacitus is not a comforting historian. He offers no easy lessons or triumphant stories. Instead, he forces readers to confront the consequences of power, the corruption of ideals, and the silence of those who should speak.

Yet it is precisely this unflinching honesty that makes him timeless. In an age of spectacle and spin, Tacitus reminds us that beneath the rituals of state and ceremony lies a struggle for truth and freedom. His Rome, filled with terror, intrigue, and occasional glimpses of integrity, is not just ancient history—it is a mirror held up to every age.

Hello, my name is Vladimir, and I am a part of the Roman-empire writing team.

I am a historian, and history is an integral part of my life.

To be honest, while I was in school, I didn’t like history so how did I end up studying it? Well, for that, I have to thank history-based strategy PC games. Thank you so much, Europa Universalis IV, and thank you, Medieval Total War.

Since games made me fall in love with history, I completed bachelor studies at Filozofski Fakultet Niš, a part of the University of Niš. My bachelor’s thesis was about Julis Caesar. Soon, I completed my master’s studies at the same university.

For years now, I have been working as a teacher in a local elementary school, but my passion for writing isn’t fulfilled, so I decided to pursue that ambition online. There were a few gigs, but most of them were not history-related.

Then I stumbled upon roman-empire.com, and now I am a part of something bigger. No, I am not a part of the ancient Roman Empire but of a creative writing team where I have the freedom to write about whatever I want. Yes, even about Star Wars. Stay tuned for that.

Anyway, I am better at writing about Rome than writing about me. But if you would like to contact me for any reason, you can do it at contact@roman-empire.net. Except for negative reviews, of course. 😀

Kind regards,

Vladimir