Introduction

Titus Livius, better known simply as Livy, stands among the most influential historians of ancient Rome. Writing during a transformative era—from the collapse of the Roman Republic to the rise of the Empire under Augustus—Livy’s work was not just a record of the past but also an attempt to shape Roman identity. His monumental history, Ab Urbe Condita (“From the Founding of the City”), sought to chronicle the rise of Rome from mythic origins to imperial greatness. More than a chronicler, Livy was a moralist, dramatist, and national storyteller whose vision helped define how Romans saw themselves—and how later generations would remember them.

In a world where history was both education and political commentary, Livy offered a compelling narrative grounded in Roman values. Though many of his volumes have been lost, his surviving books remain essential to understanding both the history and the mythology of Rome.

Livy’s Life and Background

Titus Livius was born in 59 BC in Patavium (modern-day Padua), a prosperous city in northern Italy. He respected Roman ideals and became one of the foremost voices of its cultural tradition.

Livy lived through one of the most tumultuous periods in Roman history. The assassination of Julius Caesar, the civil wars, and the eventual rise of Augustus as the first emperor all occurred during his lifetime. Yet, Livy largely stayed out of politics. He chose the pen over the sword, devoting himself to historical writing rather than political ambition.

He developed a cordial relationship with Augustus, though he never served in the imperial court or sought political office. According to the later writer Suetonius, Augustus once jokingly called Livius a “Pompeian” because of his Republican sympathies. Livy’s moderate stance, which praised the moral virtues of the early Republic while acknowledging the stability brought by Augustus, allowed him to write with a degree of intellectual independence rare in the early Empire.

Ab Urbe Condita: The Monumental Work

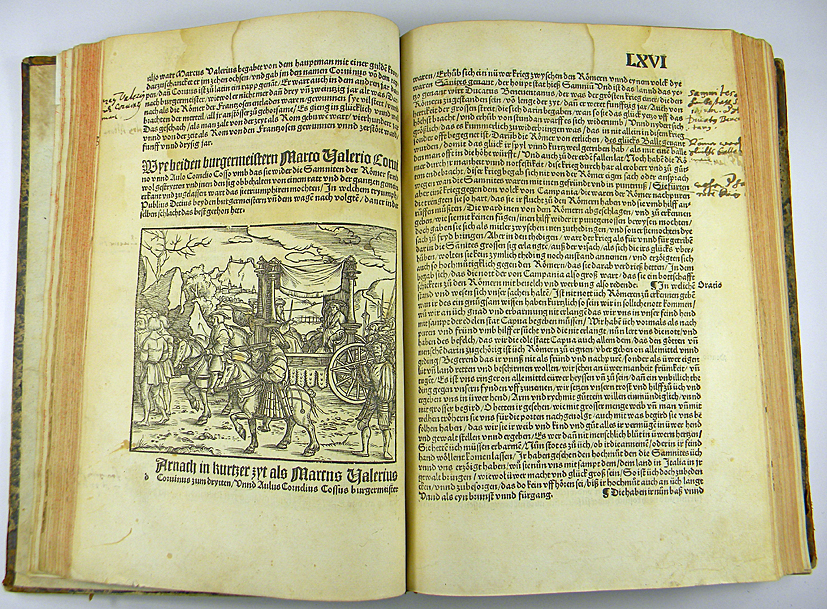

Livy’s magnum opus, Ab Urbe Condita Libri, is one of the most ambitious historical works of antiquity. Comprising 142 books, it was intended to cover the entirety of Roman history from its mythical founding in 753 BC to Livy’s present in the early first century AD. Today, only 35 of those books survive in complete form: Books 1–10 and 21–45, with the rest preserved through summaries known as Periochae.

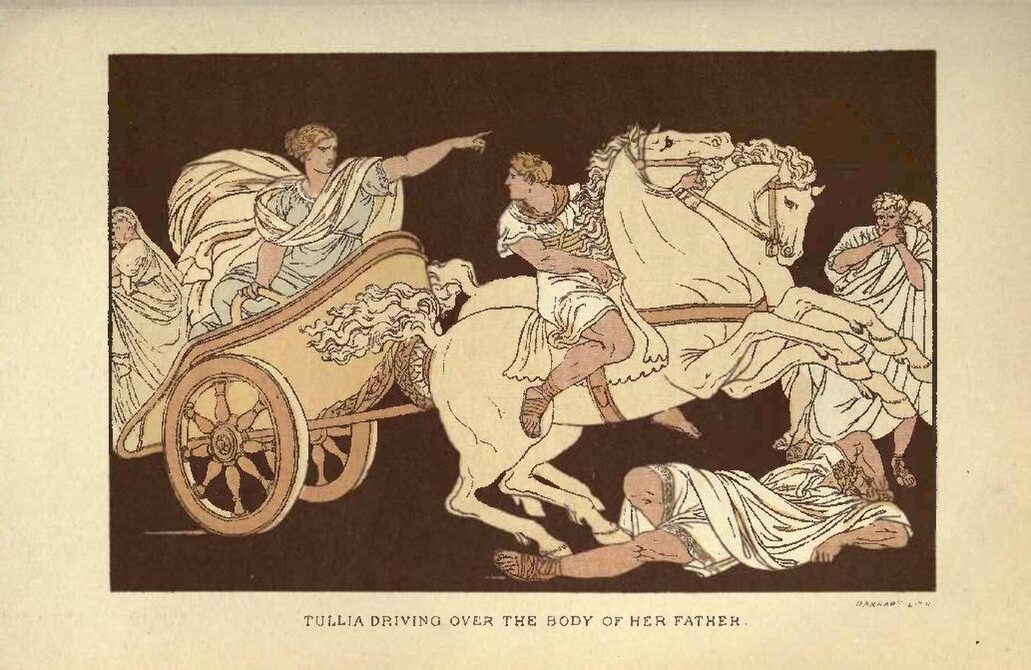

The early books explore Rome’s legendary past—Romulus and Remus, the Sabine women, and the overthrow of the Tarquin kings. These narratives are rich with dramatic episodes that convey moral and civic lessons. Later books, such as the detailed account of the Second Punic War (Books 21–30), provide character-driven portrayals of figures like Hannibal and Scipio Africanus.

Livy’s method combined literary artistry with historical documentation. While he consulted earlier Roman annalists and Greek sources like Polybius, his work is not a modern critical history. Instead, Livy crafted narratives filled with speeches, moral reflection, and national myth. His priority was not always strict accuracy but the transmission of Roman virtus—courage, loyalty, discipline, and duty.

He often dramatized events and inserted fictionalized speeches, a technique inherited from Thucydides and other Greek historians. Livy admitted his limitations: he acknowledged that much of early Roman history relied on oral tradition, lost documents, and national memory. Yet he never allowed this to weaken the grandeur of his vision.

Historical Purpose and Moral Vision

Livy’s primary aim was not to produce a purely factual chronicle but to offer a moral education through history. He famously stated in his preface that he wanted readers to reflect on the examples of the past, both good and bad. History, in his view, was a repository of exempla—moral examples that could guide citizens in virtuous living.

This moralistic vision permeates his work. He highlighted episodes of heroism, sacrifice, and honor. Figures such as Horatius Cocles, who defended a bridge single-handedly against invading forces, or Lucretia, whose tragic death sparked the fall of the monarchy, served as models of Roman civic virtue.

He lamented the decline of these values in his own time. For Livy, the moral decay of the late Republic—greed, ambition, civil strife—stood in stark contrast to the simplicity and self-sacrifice of early Rome. Though he appreciated the peace Augustus had brought, Livy subtly warned that no empire could endure if it abandoned its foundational virtues.

At the same time, Livy was not simply nostalgic. His use of history was constructive: by recalling what made Rome great, he hoped to inspire renewal. He viewed the past not as a static memory but as a living source of national identity.

Legacy and Reception

Livy’s influence was immediate and long-lasting. In ancient Rome, his works became staples of the education system. Quintilian, the first-century rhetorician, praised Livy for his “richness and eloquence” and recommended him as a model for aspiring writers.

His fame endured through the Middle Ages, even though many of his books were lost. During the Renaissance, Livy was rediscovered with enthusiasm. Humanists admired both his Latin style and his vision of civic virtue. Machiavelli, in his Discourses on Livy, used the historian’s early books as a lens through which to understand power, politics, and republicanism. Montesquieu also drew on Livy’s themes in The Spirit of the Laws.

In modern scholarship, Livy has received mixed evaluations. Critics have pointed out his credulity in accepting legends and his lack of source criticism. Yet others defend his approach as appropriate to his aims: Livy was writing not just a history, but a national epic.

His narrative skill, his ability to weave myth and fact, and his moral earnestness continue to captivate readers. Even today, Ab Urbe Condita is a central source for understanding Rome’s self-perception, and by extension, the foundations of Western political and cultural thought.

Conclusion

Livy was not merely a recorder of Rome’s past—he was a creator of its memory. Through his epic history, he offered a vision of Rome as a moral force, a city destined for greatness because of the virtues of its citizens. While modern historians may critique his factual accuracy, few can deny his literary brilliance and enduring influence.

By combining myth with moral reflection, and legend with national purpose, Livy helped forge a Roman identity that persisted long after the fall of the Empire. His work reminds us that history is not only about dates and events, but also about ideals, inspiration, and the human desire to make sense of the past.

Hello, my name is Vladimir, and I am a part of the Roman-empire writing team.

I am a historian, and history is an integral part of my life.

To be honest, while I was in school, I didn’t like history so how did I end up studying it? Well, for that, I have to thank history-based strategy PC games. Thank you so much, Europa Universalis IV, and thank you, Medieval Total War.

Since games made me fall in love with history, I completed bachelor studies at Filozofski Fakultet Niš, a part of the University of Niš. My bachelor’s thesis was about Julis Caesar. Soon, I completed my master’s studies at the same university.

For years now, I have been working as a teacher in a local elementary school, but my passion for writing isn’t fulfilled, so I decided to pursue that ambition online. There were a few gigs, but most of them were not history-related.

Then I stumbled upon roman-empire.com, and now I am a part of something bigger. No, I am not a part of the ancient Roman Empire but of a creative writing team where I have the freedom to write about whatever I want. Yes, even about Star Wars. Stay tuned for that.

Anyway, I am better at writing about Rome than writing about me. But if you would like to contact me for any reason, you can do it at contact@roman-empire.net. Except for negative reviews, of course. 😀

Kind regards,

Vladimir