Rome’s beginnings are wrapped in stories and legends, with tales of Romulus and Remus often capturing the imagination. These narratives are filled with figures like Aeneas and events like the story of Lucretia. Such stories contribute to Rome’s rich history, even if some elements blur the lines between myth and reality. One pivotal development in Rome’s transformation was the establishment of the Twelve Tables, a breakthrough in Roman law that greatly influenced the republic.

The Twelve Tables emerged after growing tensions between Rome’s social classes, as Plebeians sought more power and rights. The call for a written law was marked by significant contributions from tribunes like Gaius Terentilius Harsa. Though met with strong resistance, the push for fairer legal frameworks highlighted a shift in Roman societal norms, challenging existing power structures and setting a foundation for future reforms.

Key Takeaways

- Rome’s origins involve rich legends contributing to its historical identity.

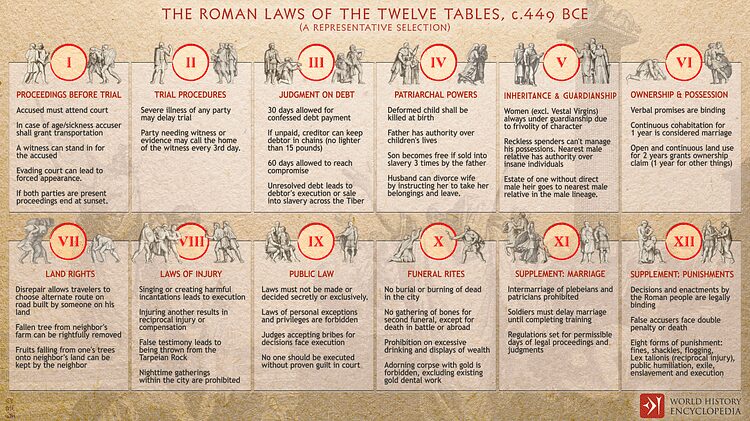

- The Twelve Tables marked a major change in Roman legal history.

- Plebeian efforts for rights pushed for fairer legal systems in Rome.

The Myths of Rome’s Beginnings

Romulus, Remus, and the Hazy Beginnings

The story of Rome’s beginnings is often linked to the twin brothers, Romulus and Remus. Their tale is filled with uncertainties, and the details are often unclear. Raised by a she-wolf, the brothers have become symbolic figures in Roman lore. Romulus, the more famous of the two, is credited with founding the city, while Remus met an untimely demise. Despite the inconsistencies, their legend remains an integral part of Rome‘s identity.

Aeneas and the Search for Ancient Roots

To cement a sense of antiquity, Romans looked further back to the story of Aeneas, a hero from the Trojan War. According to legend, Aeneas led a group of refugees from the ashes of Troy to eventual settlement in Italy. This narrative added depth to Roman ancestry, linking them to ancient civilizations and giving Rome a noble origin that its people could take pride in. Aeneas’ journey underscored the themes of endurance and destiny, enhancing Rome’s sense of historical significance.

Birth of the Roman Republic

Lucretia’s Tale and the Beginning of a New Era

The tale of Lucretia is a classic story often linked to the start of the Roman Republic. Her story involves tragic events that prompted significant change. Lucretia, a noblewoman, was subjected to a grave injustice perpetrated by a royal family member. This incident sparked outrage among Roman citizens, leading to a collective revolt against monarchical rule. The public anger and demand for justice played a critical role in overthrowing the monarchy and setting up the Roman Republic. While this story contains elements that are likely exaggerated or mythologized, it holds a pivotal place in the cultural narrative of Rome, symbolizing the struggle for justice and equality.

Views from Cato and Cicero on Republic’s Origins

Cato the Elder and Cicero held particular views on how the Roman Republic began. They both emphasized the introduction of the 12 Tables as a turning point in Roman governance. These laws signified a structural change, giving society a foundation that moved away from arbitrary rule. Despite their conservative inclinations and disdain for changes driven by the common people, both Cato and Cicero acknowledged the significance of these laws. They believed that the 12 Tables marked a critical moment when the state began to adopt a more systematic legal order. Cato saw them as a shift towards long-term stability, while Cicero viewed them as essential for the traditions he valued. This episode demonstrates that even established laws and customs can evolve to accommodate societal shifts, reflecting the dynamic nature of governance and tradition in Roman history.

The Twelve Tables: A Legal Turning Point

Popular Movement and Its Influence

The Twelve Tables, a monumental legal code in ancient Rome, originated through significant public pressure. Tribunes, who were officials chosen directly by the people, ignited this movement. They criticized the unchecked authority of the consuls, likening it to the tyranny of kings. The patricians, who held sway over Rome, guarded laws as oral traditions, fostering a system that benefited them exclusively. The call for a written law code grew louder as plebeians rallied to demand transparency and accountability. Even when faced with fierce resistance from the elite, the determination of the plebeians laid the groundwork for changing the Roman legal system.

Cicero’s Valuation and the Importance of Learning

Cicero valued the Twelve Tables highly, regarding them as essential to Rome’s legal framework. His writings indicate nostalgia for a time when children learned these laws by heart, signifying their foundational role. Despite Cicero’s appreciation, he consistently viewed the common populace as lacking true agency. This perspective created a paradox, as he admired the laws that arose from public pressure while critiquing the methods used to achieve them. His literary works reflect this tension, showing both respect for the legal traditions and disdain for popular movements.

Changes in Roman Conservative Views

In ancient Rome, the development of the Twelve Tables marked a huge change in legal and social norms. This set of laws shifted the balance of power in the Roman Republic. Even though leaders like Cato the Elder and Cicero were not fans of change, they saw the Twelve Tables as fundamental to the republic’s tradition.

Cato, famous for opposing Greek ideas, might have disliked the origins of these laws, yet he found them crucial in shaping a new era for Rome. Cicero, another important figure, valued the Twelve Tables so much that he regretted how children no longer memorized them as they once did.

Cicero’s views on the masses were complex. While he held the Twelve Tables in high esteem, he often considered the common people’s gatherings as unruly, calling them mobs. This stance aligned with his resistance to Clodius, who leveraged popular support to rise in power.

Despite the initial resistance, what began as a radical shift slowly became an accepted tradition over time. Roman conservatism adapted, shifting with societal changes and power dynamics. Legends and stories about these transformations became part of Rome’s identity, influencing how Romans viewed themselves and their history. While the tales might not align completely with modern evidence, they were integral to Rome’s culture and society.

Common Folks’ Push Back and Nobles’ Control

Early Republican Struggles for Fairness

The early days of Rome’s republic were marked by serious clashes. Common people, known as Plebeians, were not happy with how the Patricians, the noble class, held all the power. The Plebeians wanted more say in government decisions. A tribune named Gaius Terentilius Harsa took a stand by speaking out against the unchecked power of the consuls, who were like leaders with king-like authority. He argued that having two leaders with such power was worse than one king.

The Plebeians didn’t feel free, as many of the promises made when they overthrew the kings seemed empty. They were allowed to vote for representatives, but the top positions were still reserved for the Patricians. Moreover, there was no written code of laws. Laws were passed down orally and controlled by a select group of nobles, which made it easy for them to rule in their favor. This lack of transparency and fairness in the legal system angered the Plebeians. They strongly supported Terentilius’ call for a written law code that everyone, including the consuls, would have to follow.

The Demand for a Written Law Code

The push for a law code began as Plebeian leaders saw the need for accountability and fairness. The lack of written laws meant the Patricians could interpret rules as they wished, often to their own benefit. This became a central issue when common people demanded laws be written down so everyone knew their rights and responsibilities.

The Patricians resisted fiercely, viewing the demand as a threat to their privileged status. They went so far as to accuse reformers like Terentilius of treason. Still, the Plebeians pushed on. They managed to elect the same popular tribunes repeatedly, showing strong support for their cause. Despite ongoing conflicts, the Plebeians finally secured a small victory in 457 when they increased the number of tribunes to ten. Although this was not the complete victory they sought, it was a step toward equality and set the stage for future changes.

Notable Events Leading to the Twelve Tables

Tribune Gaius’ Suggestion and Plebeian Support

In the early days of the Roman Republic, dissatisfaction grew among the common people. Gaius Terentilius Harsa, a tribune, saw a chance for change when the consuls were away. He criticized the power of the patricians and likened the consuls’ authority to that of kings. Though elections existed, real power lay with the patricians, who kept unwritten laws secret. Gaius pushed for a written code accessible to all, rallying significant plebeian support. Despite this, patricians blocked his effort, labeling him a traitor.

Rising Conflicts and Political Struggles

Tensions mounted as plebeians became more frustrated by the refusal to create a written law code. They re-elected the same tribunes repeatedly to press their case. The city experienced significant unrest, likened to “political warfare,” with ominous signs in the city. The plebeians’ fight for fair rules persisted, with both sides deeply at odds.

Pressure, Compromises, and the Ascendancy of Tribunes

Amidst growing tensions, a crisis in 457 B.C. arose with enemy threats from neighboring groups, which gave plebeians leverage. They succeeded in increasing the number of tribunes, although this didn’t completely meet their demands. Discontent flared again with food shortages. A bold tribune, Claudius, took a stand by prosecuting a former consul for corruption, which underscored plebeian determination for justice.

The Role of Tribunes in Plebeian Advocacy

In ancient Rome, tribunes were elected officials who represented the interests of the plebeians, the common people. They had the authority to challenge the decisions of the patricians, the aristocratic class, and acted as protectors of the plebeians’ rights and interests. This was a crucial role since the patricians held the majority of political power and often imposed their will without considering the needs of the broader population.

Gaius Terentilius Harsa, a notable tribune, saw an opportunity to confront the dominance of the patricians when the consuls were absent. He argued that the consuls’ powers were as oppressive as those of kings, highlighting that the promised freedom from tyranny was not delivered. Instead of one king, Rome had two consuls, who wielded unchecked authority over the people.

During earlier decades of the Republic, although elections were held, true freedom was elusive for the plebeians. Key positions and priesthoods were limited to patricians. Furthermore, the absence of a written law code meant justice relied on unwritten laws, known only to the privileged patrician priesthood. This lack of transparency and accountability led many plebeians to support Terentilius’ call for a written law code.

Terentilius’ efforts faced stiff resistance from the patricians, who portrayed him as a traitor for demanding adherence to republican principles. Despite strong popular backing, his proposal was blocked. The conflict between plebeians and patricians continued over the next five years, with plebeians persistently electing the same tribunes to push their agenda. The situation escalated into a crisis marked by intense political strife, and eventually, some concessions were made, increasing the number of tribunes.

Although increasing the number of tribunes was a step forward, it was not the complete solution plebeians sought. Discontent resurfaced during a famine the following year, as resources became scarce. Tribunes continued to advocate for the people’s needs, at times resorting to legal actions against officials accused of corruption, emphasizing their critical role in advocating for plebeian rights and seeking justice.