You live in a world that treats year numbers as fixed and obvious. I speak to you at a moment tied to a familiar label, yet that label rests on choices made long ago. You use it every day, but few stop to ask where it came from or why it works the way it does.

I guide you through how people once tracked time without shared year counts. You see how rulers, cities, faiths, and scholars shaped systems that served local needs before one method spread wider. You learn why the system you use today endures, even with its limits.

Key Takeaways

- Year counting developed unevenly across cultures.

- Religious and political needs shaped shared timelines.

- Modern dating works by agreement, not precision.

Early Ways People Counted Years

How Greek Cities Marked Time

You do not see a single Greek way to number years. Each city used its own system, tied to local officials or religious roles.

- In Athens, you named the year after the eponymous archon.

- In Sparta, one of the ephors gave the year its name.

- In Argos, the priestess of Hera filled this role.

This variety made history hard to track. Greek writers had to match events across systems or choose one city as a reference.

You do find longer timelines in special cases. The Olympiad cycle counted four-year periods linked to the Olympic Games, dated from what you call 776 BC. Historians used it, but daily life did not.

| Greek Method | What Defined the Year | Common Use |

|---|---|---|

| City officials | Name of a magistrate | Local records |

| Olympiad cycle | Four-year games | Historical writing |

| Seleucid era | Years since a royal victory | Near Eastern regions |

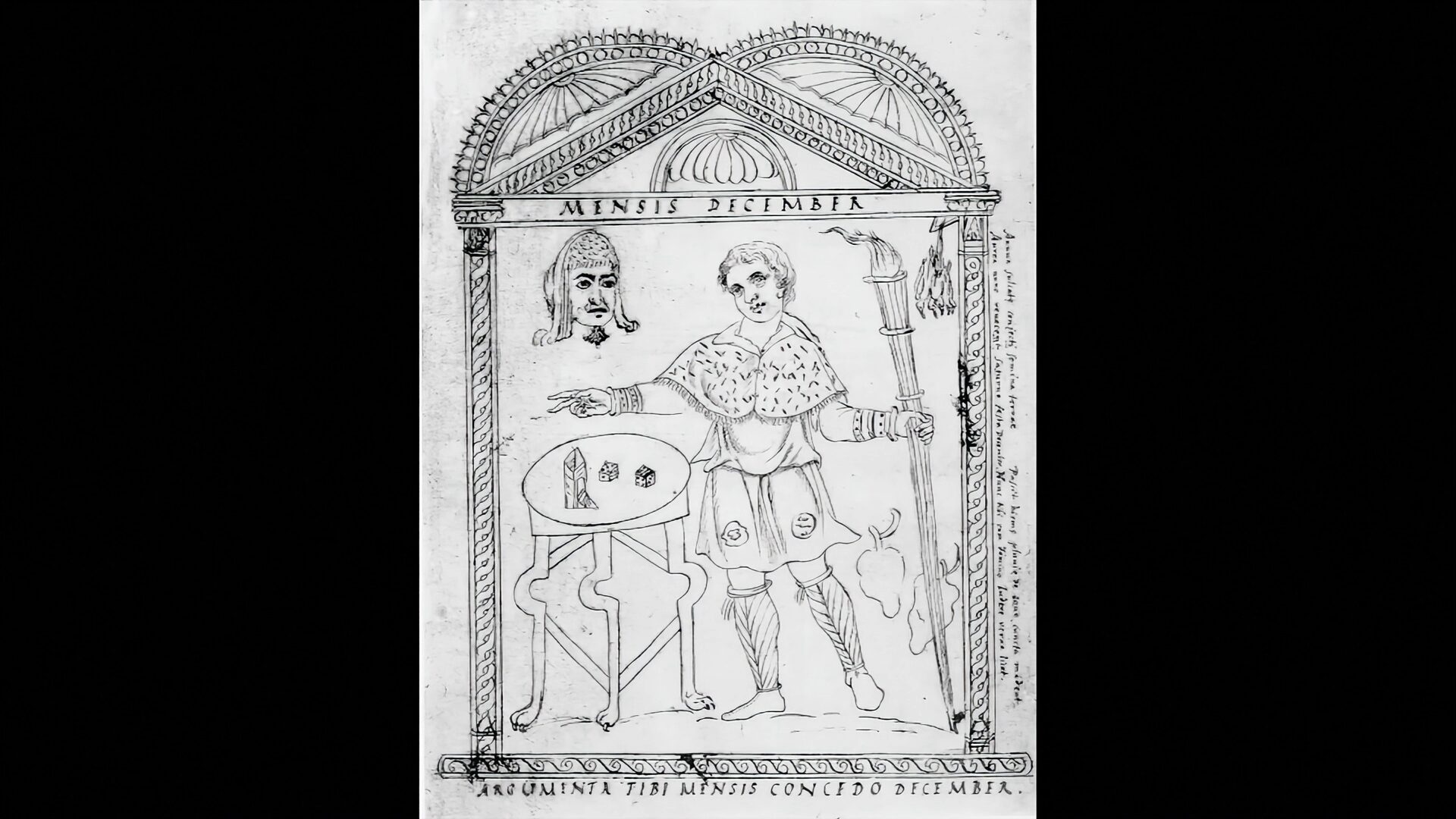

How Romans Labeled Their Years

You date Roman years by the names of officials, not by numbers. Each year took the names of the two consuls who entered office, usually on January 1.

In casual speech, you might mention only one consul. A famous wine from 121 BC, for example, took its name from a consul of that year.

Roman scholars sometimes counted years from the founding of Rome. This method, often placed around the mid‑700s BC, never replaced consular dating.

| Roman Method | Basis | Where You See It |

|---|---|---|

| Consular naming | Two serving consuls | Law and public life |

| Years from Rome’s founding | Traditional foundation date | Historical works |

You still see consular dating well into late antiquity, even as new systems begin to appear.

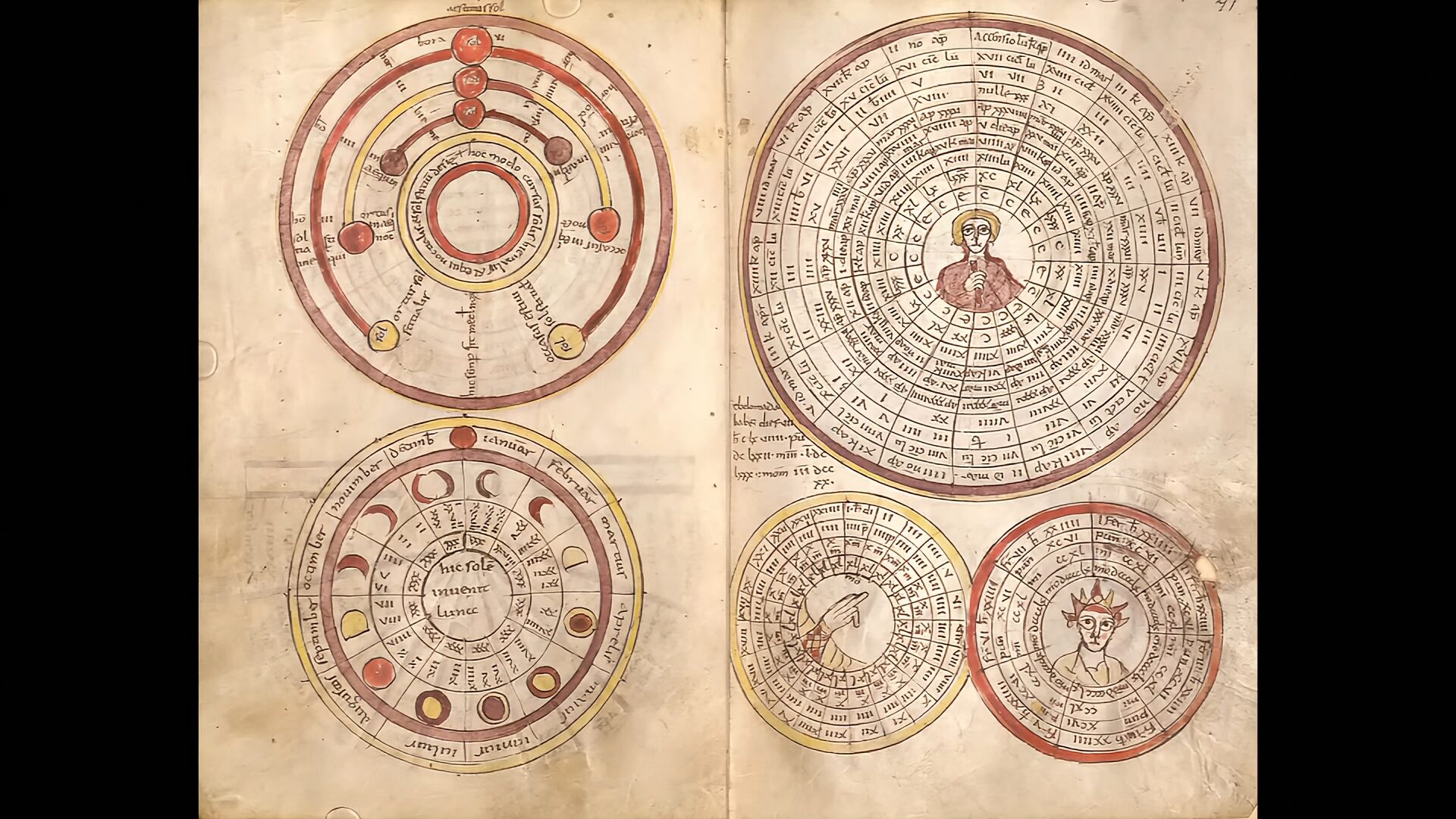

Key Systems for Tracking Time

Dating by Olympic Cycles

I point out that Greek writers sometimes tied events to the Olympic Games, which took place every four years. You would hear dates described by the number of the games rather than a numbered year. Historians used this method more than ordinary people.

| Feature | Detail |

|---|---|

| Starting point | Games counted back to 776 BC |

| Main users | Greek historians |

| Daily use | Rare |

The Era of the Seleucid Kings

I explain that one Greek-style system did count years in a steady sequence. You see this system begin with Seleucus I taking Babylon in 312–311 BC. People across the Near East kept using it long after his dynasty ended.

- Used far beyond Greece

- Lasted into modern times in some communities

Years Named for Roman Officials

I note that Romans marked each year by naming the two consuls in office. You could date events by listing one or both names, and this practice stayed normal even under emperors. Legal records followed this rule closely.

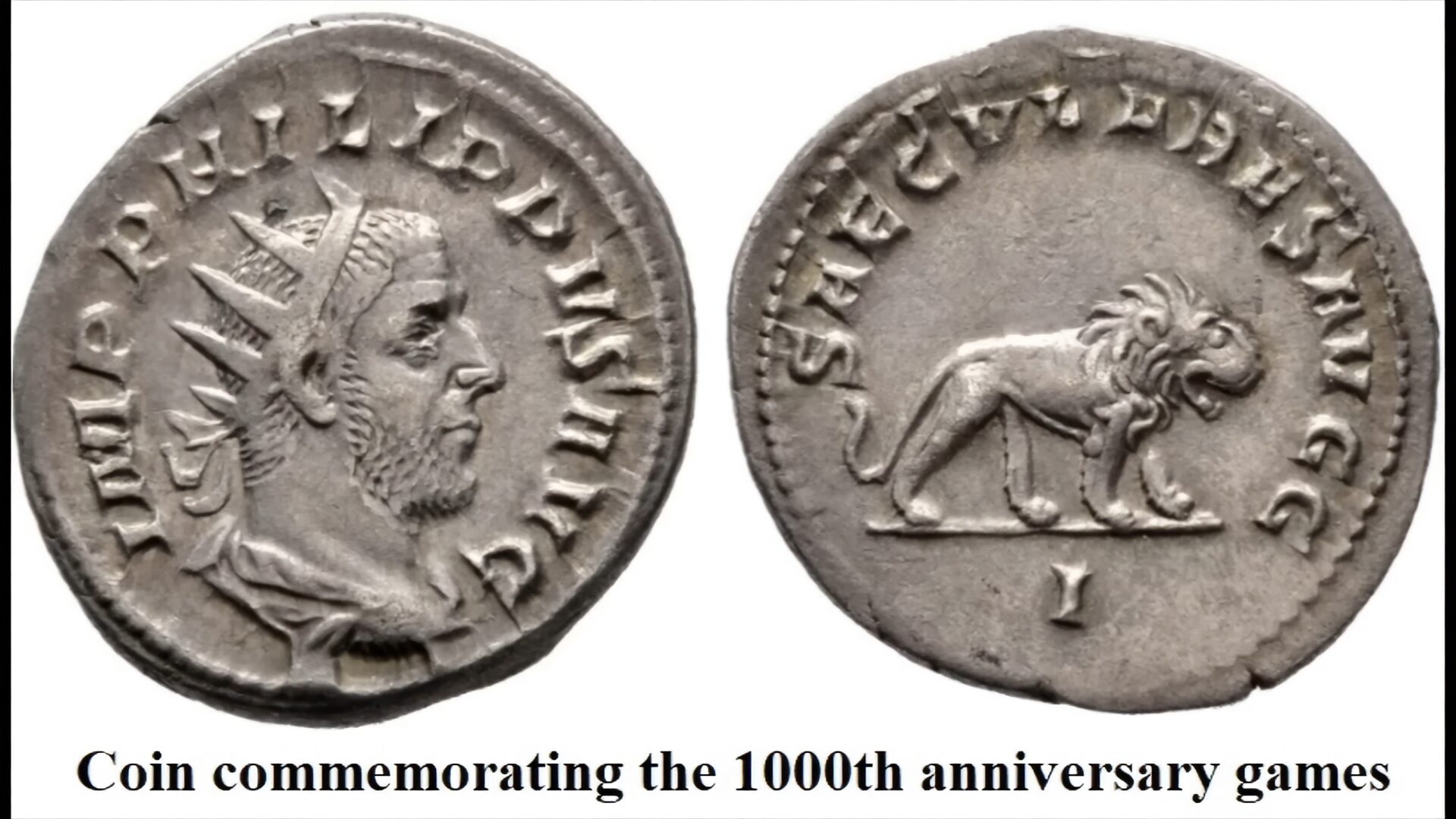

Counting from Rome’s Founding

I mention that some Roman scholars counted years from the start of the city of Rome. You should know that no single founding date ever won full agreement. The date of 753 BC became common because one scholar’s calculation spread widely.

Typical use:

- Historical writing

- Rare coins and anniversaries

Fifteen-Year Tax Cycles

I describe a late Roman system based on repeating tax periods. You would see dates tied to a cycle, not a numbered year. This method can confuse you today because the cycles were not numbered.

Years of an Emperor’s Rule

I add that late antiquity also used the length of an emperor’s reign to mark time. You date an event by stating which year of that ruler’s power it occurred. This method became common by the sixth century.

Growth of Christian Time Reckoning

First Christian Methods of Dating

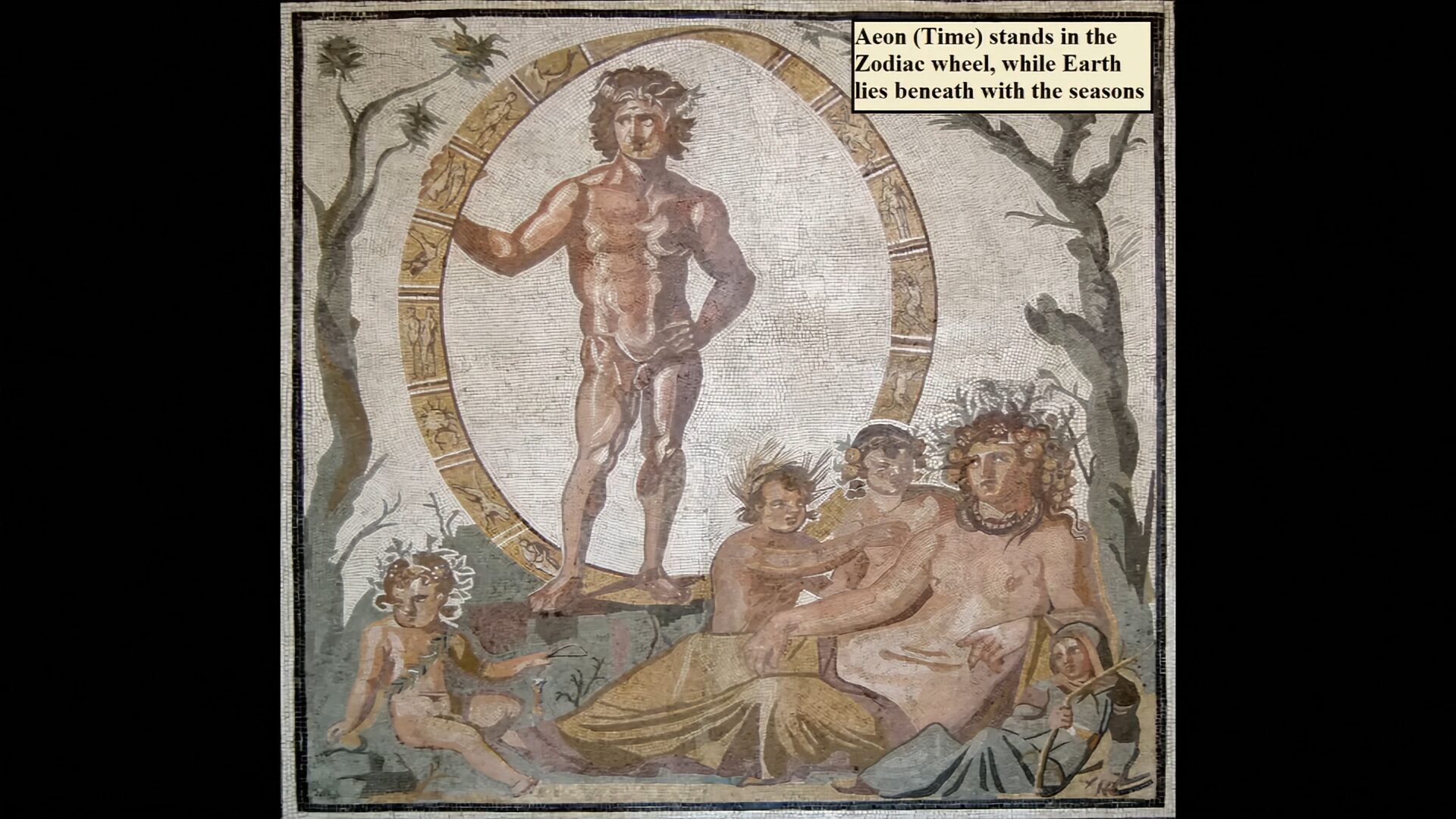

You see early Christian scholars shift focus from local calendars to a shared timeline. You calculate history from the moment of creation because many believers expect the world to last 6,000 years.

You rely on scripture to fix that starting point, but results differ by region.

| Region | Chosen start of creation |

|---|---|

| Greek-speaking churches | 5509 BC |

| Western Europe | Around 4000 BC |

You build long chronicles from these dates and treat them as serious tools for study and belief.

You later see a new idea take shape in the sixth century. You begin counting years from the birth of Jesus when Dionysius Exiguus creates this system while working out Easter dates. You do not design it to rule daily life, but scholars slowly adopt it.

Timekeeping Based on the Martyrs

You also use another system that reflects persecution and memory. Egyptian Christians mark years from 284, the year Emperor Diocletian takes power.

You call this system the Era of the Martyrs. You keep using it long after other regions move on.

You choose this count to honor suffering rather than kings or cities. You still use it today in some Egyptian Christian communities.

Growth and Reach of the Anno Domini Dating System

Dionysius Exiguus and the Original Year Count

You see the Anno Domini system begin in the sixth century with Dionysius Exiguus, a Roman monk skilled in math.

While you calculate future Easter dates, he chooses to number years from the birth of Jesus instead of from an emperor’s reign.

He does not aim to build a global system.

You watch the method spread slowly and by accident.

How the System Took Hold in Europe

You first find this year count used in Anglo-Saxon England, driven by the eighth-century scholar Bede.

From there, you see it move across regions over time.

Timeline of wider use

- Late 800s: common in France and western Germany

- By 1000: widely used in Italy

- 1300s–1400s: adopted in the Spanish kingdoms

Use in Church and Scholarly Work

You notice that even after adoption, people use Anno Domini mainly in church records and academic writing.

Daily life still relies on older systems for many centuries.

You do not see broad secular use until the early modern period.

The system remains a tool for learned and religious settings first.

The Later Addition of “Before Christ”

You might expect BC to appear at the same time, but it does not.

You only see BC become common in the late eighteenth century.

You also learn that Dionysius misdated the birth of Jesus.

That error does not change the system’s role, since it works as a shared convention, not a claim of precision.

Limits and Effects of How Years Get Counted

You deal with a system that feels natural, but most past societies did not count years this way. Many calendars tracked seasons and festivals, yet they avoided numbered years, which made long timelines hard to share across places.

Different cities used different names for the same year. That caused real limits for historians and officials who tried to match events.

- Athens named years after an archon.

- Sparta named years after an ephor.

- Argos used the priestess of Hera.

These local rules forced writers to choose one system or stitch systems together. That slowed record keeping and raised the risk of errors.

Some broad systems helped but stayed limited in use.

| System | What it Used | Limits on Daily Use |

|---|---|---|

| Olympiads | Four-year games | Mostly for historians |

| Seleucid Era | Start of Seleucus’ rule | Regional, not global |

| Consular Dating | Names of consuls | Confusing outside Rome |

| Ab urbe condita | Rome’s founding | No single agreed date |

Later systems created new problems. Indiction cycles named a tax period but did not number the years, which leaves you unsure which year a source means. Regnal years tied dates to emperors, so dates changed meaning when rulers changed.

Christian chronologies aimed for a universal timeline, but even they disagreed. Scholars argued over the date of creation, and regions kept their own eras. When the A.D. system appeared, you see that it spread slowly and stayed limited to church and academic use for centuries.

The key impact is practical. A.D. works because many people accept it, not because it is precise. Even its starting date is off, yet the system still helps you line up events across cultures and time.

Conclusion

You rely on year numbers as if they are fixed and natural, yet they come from choices made long ago. When you look closer, you see that many societies tracked time without counting years at all.

You can place these systems side by side:

| Approach | How it marked time | Who used it |

|---|---|---|

| Named years | A year took the name of an official | Greek cities and Rome |

| Event cycles | Dates linked to repeating games | Greek historians |

| Founding eras | Years counted from a city’s start | Roman scholars |

| Religious eras | Years tied to sacred events | Christian communities |

You also see that the A.D. system grew by chance, not by design. Even with a flawed birth date for Jesus, you still use it because shared conventions help you talk about the past with clarity.