Caesar and Rome During the Civil War

Before the dictatorship and even during the civil war, upon entering the city, Caesar began his work on the reorganization of the Roman state and initially filled the Senate with his supporters. Lepidus was given the position of praetor and was appointed temporary governor of the city of Rome, and the tribune of the people, Mark Antony, was appointed governor of Italy. He sent Curio to Sicily, Quintus Valerius to Sardinia, and in order to prevent Pompey’s land attack, he sent Gaius Antonius to Illyricum, and entrusted this part of Gaul to Marcus Licinius Crassus, son of the deceased triumvire.

Caesar maintained the appearance of a republican system as long as it was in his interest; an anecdote about the embezzlement of money intended for defense against the Gauls speaks in favor of this claim. In December 49 BC, before crossing the Adriatic Sea, Caesar stayed in Rome to pass certain laws and elect magistrates and governors of the provinces. Since most of the senators and magistrates had left Rome, it was not possible to elect new ones, and Lepidus therefore decided to declare Caesar dictator in order to maintain the appearance of respect for the law.

The First Dictatorship

Caesar elected magistrates for the following year and restored dictatorial powers after eleven days. He elected himself and Servilius Isauricus as consuls. Before leaving for Brindisi, he abolished Sulla’s proscriptions, so that the descendants of those punished had the right to engage in political activity. He also passed a law against usury, which prohibited interest from exceeding one quarter of the capital. It was forbidden to keep a figure higher than 15,000 denarii out of circulation, but he refused requests to cancel debts.

In the spirit of his benevolence, he also allowed the return of exiles. After going to war, Caesar did not return to Rome for a long time, which was led by his followers. Caesar was re-elected dictator in absentia after news of the victory at Pharsalus arrived, and his mandate was entrusted to him for a year. Mark Antony was appointed commander of the cavalry, but he was unable to maintain control over the city and Italy, so that order often turned into anarchy.

Caesar saw the city of Rome again after the victorious war with Pharnaces. Before his arrival, he faced a rebellion of the army that demanded dismissal and rewards. The rebellion quickly became violent, so that even two praetors lost their lives. Caesar only ordered the soldiers to disperse with the promise of payment of rewards, but his very appearance changed the behavior of the army, and the soldiers now asked to continue fighting for him.

Caesar was most disappointed at this time with his famous Tenth Legion, which had voluntarily requested to be decimated, which Caesar refused and pardoned for mutiny. The morale of the army was once again at a high level.

In Rome, he held consular elections and completed the filling of the Senate with his supporters before leaving for the war in Africa. At that time, Caesar again renounced the title of dictator. As high priest, Caesar carried out a reform of the Roman calendar, which had been in chaos before the civil war, by adding 67 days between September and December in 46 BC and the introduction of a solar calendar based on the calculations of Sosigenes, an Alexandrian scientist of Greek origin.

Dictatorship or Monarchy?

Upon his return from Africa, Caesar gave a speech in which he glorified his conquests, pompously announcing the huge influx of money in the form of taxes from the newly created provinces. He then celebrated a quadruple triumph that lasted from September 20 to October 1, 45 BC. The triumph over Pompey was disguised by celebrating victories over external enemies, the Gauls, the Egyptians, Pharnaces, and Juba, and the four-year-old son of Juba, Cleopatra’s sister, and Vercingetorix were led in the triumphal procession.

Caesar received various honors that began to cross the border of Roman republican principles. He was given the right to always speak first in the Senate and to have his name engraved on the Capitoline Temple, and was even celebrated as a demigod. Caesar accepted all these honors. Caesar was proclaimed dictator for the third time in 46 BC, this time for a term of ten years. This dictatorship differed from the rule of the monarch only in name.

No one was left to challenge his rule. The old aristocracy no longer existed, and the younger aristocracy that had sided with Pompey had changed sides and was well rewarded for it. Cicero remained silent, grateful to be in Rome at all and frightened by everything that had happened to him in the past. His gratitude exceeded the bounds of decency. Certainly, Cicero was not the only one who exaggerated in flattery towards Caesar. Caesar continued to be benevolent towards the vanquished. He ordered the demolished statues of Pompey to be rebuilt, while Brutus and Cassius became praetors.

Caesar set about enacting new laws. First, he took care of his veterans, who were settled in Italy as landowners, rather than as colonists as had been the case before. He passed a law on immigration that encouraged people of certain professions to settle in Rome. Rome had lost a large number of inhabitants during the civil wars.

Three laws were proposed by Caesar and implemented after Caesar’s death. The first law listed provisions for the free distribution of grain. The number of recipients of free grain was reduced from 320,000 to 150,000. There were magistrates who compiled a special list of citizens who were qualified to receive free grain. To ensure a more regular supply of grain, a plan was made to create a spacious artificial harbor at Ostia.

The second law determines the provisions on the duties of the aediles and the magistrates subordinate to them. Among other things, it provides for the maintenance of roads and supervision of the squares. The third law establishes the equalization in administrative terms of all the cities of Italy: autonomy in resolving local issues, established rules for the election of city magistrates, the age limit for magistrates (30 years), the number of senators…

Upon returning from the last war in Hispania, Caesar was greeted with the greatest honors that exceeded the limits of any taste. He was awarded the title of Father of the Fatherland, his birthday was declared a public holiday, and the month of his birth was named July. He had a special chair in the Senate and was always allowed to wear a triumphal toga. Caesar refused none of the honors offered to him. The monarchy was increasingly mentioned, with the public’s disapproval being loudly expressed. After all, he was granted a dictatorship for life in 45 BC.

Any attack on him was considered sacrilege, and the senators swore to always protect Caesar. Close ties with Cleopatra and their son, disparagingly called Caesarion, as well as the arrival of the Egyptian queen in Rome, increasingly showed that Caesar aspired to a monarchy. Although Caesar publicly refused to declare himself king and bear the ancient title of rex, events indicated that he had chosen that path.

Before the spring, Caesar was preparing a large army against the Parthians and probably did not want to imply the monarchy and then set off on a long journey, leaving the most warlike areas of the Roman state far behind him. It is a big question whether Caesar would refuse full power when he returned from a great campaign (let’s assume it was successful), with enormous booty and military glory. There was an old prophecy that the Romans would not be able to defeat the Parthians until they were led by a king.

Frequent, supposedly spontaneous outbursts of feeling that the city needed a king offended the republican feelings of the Romans. After all, Caesar already behaved as if he was above the rest. Once, when some honors were voted for him and when the praetors approached him, he greeted them without standing, which greatly upset the assembled crowd.

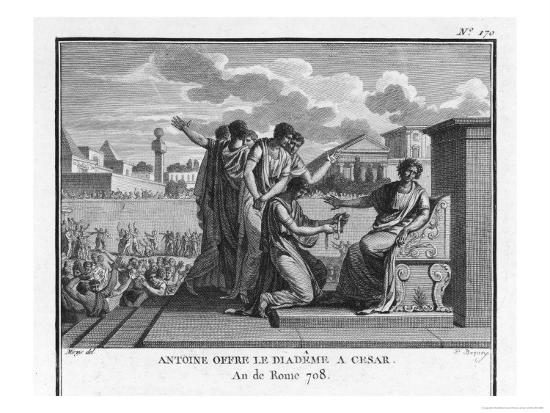

During the February celebrations, Mark Antony offered Caesar a laurel wreath, which he refused. In this way, the readiness of public opinion for the monarchy was tested, as the reaction of the assembled crowd, which was not in favor of the idea of the monarchy, was awaited. The people’s tribunes then sent to prison those who greeted Caesar as king, and Caesar took away their tribunate in response. Caesar acted as the all-powerful ruler that he was, but the aristocracy still had enough strength to fight back, and an opposition conspiratorial party began to form to try to put an end to the dictatorship.

Sources and Literature:

The Cambridge Ancient History IX (2008),

Beard, M. (2015). SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome.

Plutarch. (1859). Plutarch’s Lives: translated from the original Greek, with notes, critical and historical, and life of Plutarch. New York: Derby & Jackson,

Morey, W. C. (1900). Outlines of Roman history: For the Use of High Schools and Academies,

Appianus, of Alexandria. (1902). Appianou Romaikon Emphylion A = Appian, Civil Wars, book I. Oxford: Clarendon Press,

Hello, my name is Vladimir, and I am a part of the Roman-empire writing team.

I am a historian, and history is an integral part of my life.

To be honest, while I was in school, I didn’t like history so how did I end up studying it? Well, for that, I have to thank history-based strategy PC games. Thank you so much, Europa Universalis IV, and thank you, Medieval Total War.

Since games made me fall in love with history, I completed bachelor studies at Filozofski Fakultet Niš, a part of the University of Niš. My bachelor’s thesis was about Julis Caesar. Soon, I completed my master’s studies at the same university.

For years now, I have been working as a teacher in a local elementary school, but my passion for writing isn’t fulfilled, so I decided to pursue that ambition online. There were a few gigs, but most of them were not history-related.

Then I stumbled upon roman-empire.com, and now I am a part of something bigger. No, I am not a part of the ancient Roman Empire but of a creative writing team where I have the freedom to write about whatever I want. Yes, even about Star Wars. Stay tuned for that.

Anyway, I am better at writing about Rome than writing about me. But if you would like to contact me for any reason, you can do it at contact@roman-empire.net. Except for negative reviews, of course. 😀

Kind regards,

Vladimir