In the world of ancient Rome, gladiators held a unique place in society. Known for their courage and combat skills, these fighters battled for glory and survival in the arena. Although many never lived to see retirement, a few exceptional ones earned freedom after fulfilling their contracts or impressing sponsors with their prowess. With each match, they faced the harsh reality of potential death, yet those who managed to leave the arena had to navigate a world where their options were limited due to social stigma.

After stepping away from the spotlight, retired gladiators found new roles in society. Some continued to fight in exhibition matches, while others trained new fighters or served as referees. Despite their contributions to entertainment and culture, gladiators often remained on the fringes of Roman society. Even outside the arena, their influence persisted, as some became bodyguards, farmers, or gained respectability in certain regions. Their lives reflected the complex dynamics of honor and infamy, illustrating how they captivated the public imagination and left a lasting legacy.

Key Takeaways

- Gladiators faced a high risk in the arena, yet some earned freedom and wealth.

- After retirement, they explored new opportunities despite being socially marginalized.

- Their influence extended beyond the arena, impacting politics and culture.

Life and Death of Gladiators

Reality’s Cold Winds: Life Expectancy and Survival Chances

Gladiators faced a harsh reality. Many never lived to see retirement. They stepped into the arena, knowing it could be their last fight. Although the chance of dying in a single match was about 20% in the early years, facing the arena over 100 times meant every fight added risk. Some gladiators, bound by sentences or contracts, received freedom after fighting for three to five years. Occasionally, gifted fighters were granted freedom during events, signified by the awarding of a wooden sword known as a rudus. Despite the dangers, a few gladiators went on to live long lives. One such fighter, named Suus, lived to 99, as recorded by his tombstone.

Blade’s End: Honoring Retirement

Retirement could come after a stunning career or upon completing a sentence. Gladiators who won favor or displayed exceptional skill might be granted freedom in front of cheering crowds. The tale of Emperor Titus freeing two fighters stands as a testament to such gestures of mercy. Although gladiators were often ostracized socially, they sometimes gained enough fame to continue in exhibition matches. Otherwise, they might take roles as referees, trainers, or even transition to mundane lives.

Rewards of Glory: Payment and Prizes

Gladiators received pay for each fight, with additional rewards for victories. For example, Emperor Claudius was known to throw gold coins to those who impressed him, while Emperor Nero awarded the gladiator Spiculus an estate and mansion. Yet, few could sustain their lifestyle solely through winnings, and many had families to support. Some ex-gladiators returned to fight, drawn back by fame and financial need, earning sizable sums for single appearances.

Beyond the Arena: Life After Gladiator Retirement

Legacy and Wealth: Retired Fighters’ Lives

When gladiators stepped out of the arena for good, life presented both challenges and opportunities. Those who survived long enough to retire often did so because they completed their agreed-upon terms or received recognition from game sponsors. Emperor Titus once freed gladiators based on their performance. Rewards were not just symbolic; financial gains included coins tossed by admirers like Emperor Claudius. Though some like Spiculus received extravagant gifts, maintaining wealth long-term was a struggle. Many gladiators had families and responsibilities beyond their fame.

Chains of Disgrace: Social Barriers for Ex-Fighters

Despite their fame, former gladiators faced significant social hurdles due to their status as infames, a term signaling their disgrace. This standing prevented them from fully participating in civic life, such as holding public office or making legal decisions about their estates. Thus, societal limitations continued to weigh on their futures long after they fought their last battles.

New Dawn of Career: Continuing the Battle

Some retired gladiators couldn’t leave the arena behind. Their skill and popularity often brought them back for special events, enjoying high compensation for their appearances. Others took roles as referees, supervising matches and maintaining order. Their knowledge of the sport also made them valuable trainers, preparing new fighters for their own turn in the spotlight.

Paths Diverge: From Guardians to Farmers

Unlike those who stayed connected to the sport, some gladiators opted for quieter lives. Many became bodyguards, drawing on their combat skills to protect travelers or important figures. Gladiators were sometimes turned into makeshift soldiers during chaotic times. Others left violence altogether, embracing a more peaceful existence as farmers. Yet, the legacy of their fighting days often lingered, affecting how they were perceived or what roles they could pursue within society.

Influence on Society and How It’s Viewed

Protectors of Wealth: Guards and Mounted Soldiers

In ancient Rome, the role of gladiators extended beyond the arena. Some gladiators turned into bodyguards during political chaos. These former fighters were hired by politicians and aristocrats for protection. An example of this is when Nero surrounded himself with gladiators as he went about town. These skilled combatants were also formed into a cavalry unit by Julius Caesar during the Republic’s civil wars.

Icons of Power: From Reverence to Personal Guards

Gladiators held a special place in Roman society. Even though they were generally seen as unreliable soldiers, their skills were still respected. Additionally, some gladiators became priests or even gained honorary citizenship in eastern provinces, rising above their low social standing. Despite the limitations, their children were not restricted in the same way and could achieve higher status, even reaching the equestrian ranks.

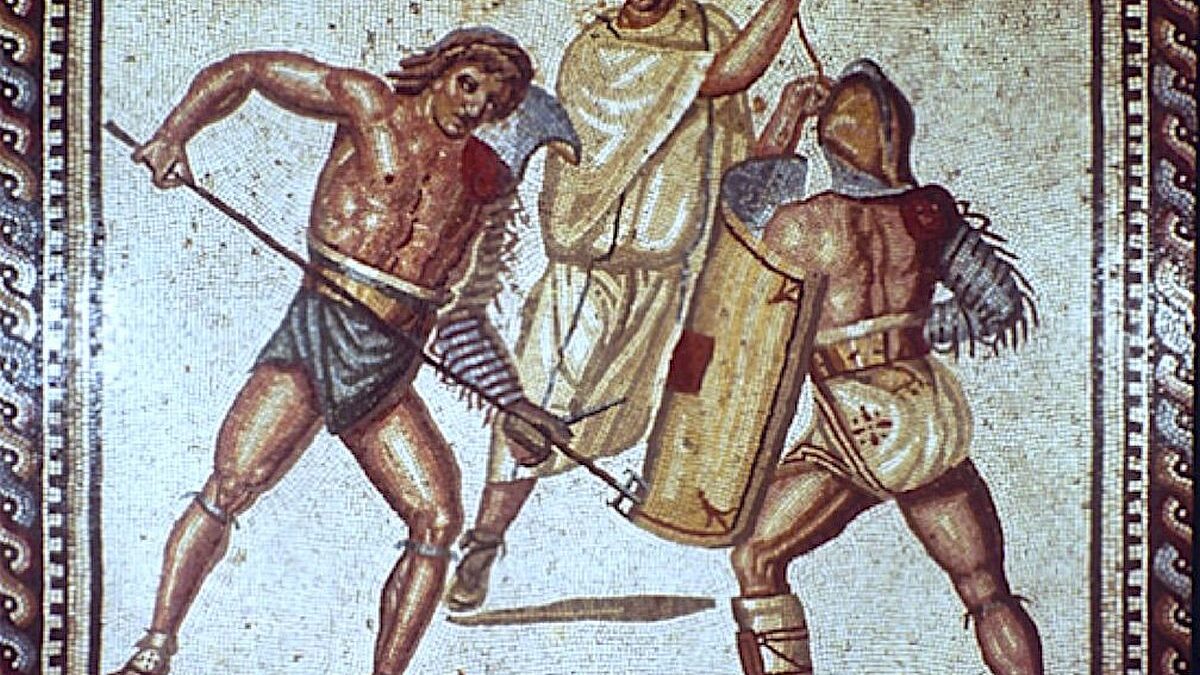

Curtain of Performance: Warriors in Art and Gossip

Gladiators were a major part of Roman life, featured in art and stories. They were known for their appeal, both on the sands of the arena and in social scenarios. There were rumors of gladiators’ romantic involvements with women from the Roman elite, illustrating their charm and allure. Gladiators’ images appeared in mosaics and were imprinted on everyday items like lamps, highlighting their pervasive influence in Roman culture.

Rod of Auctoritas: Gladiators and Political Engagement

Gladiators in ancient Rome played varied roles beyond the arena. Some embraced jobs as guards and were hired by wealthy individuals, including politicians. Notably, Clodius and Milo, two political rivals, relied on them for protection. Gladiators even accompanied Emperor Nero and his companions when they ventured into local taverns.

Though Gladiators were often kept out of the Roman army due to social stigmas, there were exceptions. Amid the Republic’s civil wars, Julius Caesar used them as cavalry, and during Emperor Otho’s reign, 2,000 Gladiators were enlisted as legionaries. Caligula further broke precedent by making Thracian Gladiators captains of his personal guards.

In rare cases, former Gladiators entered other areas of life, such as farming. The poet Horace likened his retirement to a Gladiator leaving the fight for a peaceful life on an estate. Some may have become priests of the war goddess Bellona or contenders for the priest-kingship of Nemi. Although barred from public office in Rome, some achieved recognition in the Eastern provinces, where one ex-Gladiator became an honorary citizen of several cities. Emperor Vitellius even elevated a former Gladiator to the equestrian order.

Despite their low rank, society often admired Gladiators. Their appeal went beyond physical prowess; rumors suggested romantic liaisons with high-ranking Roman women, enhancing their mysterious allure. Such tales reveal the complex roles Gladiators held, both in political life and personal relationships.

Reflections of Valor: The Mysterious Afterlife of Gladiators

Gladiators lived a life of intense action, but few managed to enjoy a peaceful retirement. Most faced their end in the arena, their bodies dragged out through the funeral gate. Despite the odds of surviving a single match being relatively low in the first century, some fought over a hundred times throughout their careers.

Retirement Rewards

Some gladiators were fortunate enough to retire after completing contracts, which usually lasted between three to five years. Those who exhibited exceptional skill might be granted a rudus—a wooden sword symbolizing freedom. Even emperors, like Titus and Claudius, occasionally freed gladiators for their performances, sometimes showering them with riches or gifting them estates.

Life After the Arena

Retirement from battle did not always secure a comfortable life. Although some saved enough to support themselves, the career options for retired gladiators were limited. Their low social status barred them from many of the benefits of Roman citizenship, such as holding office or appearing in court.

Career Paths

Despite these limitations, some retired gladiators continued to fight, often invited back for well-paying exhibition matches. Others became referees in the arena, overseeing fights with authority. Training new fighters was another viable path, as former gladiators’ experience was highly valued in gladiatorial schools.

Alternative Pursuits

Outside the arena, some gladiators adapted to diverse roles like bodyguards or even more peaceful pursuits such as farming. The chaotic political landscape of the Roman Republic sometimes allowed gladiators to serve as soldiers or personal guards for powerful figures. A few achieved social mobility, notably in the Eastern provinces, where they were occasionally honored and respected.

Gladiators, although infamous by status, were woven into the fabric of Roman society. Their legacy was marked by their burgeoning influence despite systemic restrictions. Throughout their career and beyond, gladiators left a memorable imprint on Roman life that resonated through stories, arts, and society’s perception of valor and strength.

Eternal Ephemera: Gladiators in Popular and Religious Imagination

Gladiators were central figures in Roman culture, celebrated and scorned in equal measure. Despite their low social standing, they captured the imaginations of both commoners and emperors. The skills and bravery they displayed in the arena turned them into celebrated figures, even as they faced significant societal limitations. Some gladiators met their end on the sands, but those who survived could sometimes retire, often after years of fighting. If they were lucky, a wooden sword known as a rudus could be their ticket to freedom, awarded for exceptional performance.

In the eyes of the public, gladiators might seem like larger-than-life figures. They were subjects of artwork, their images preserved in mosaics and on lamps. Stories of their exploits and supposed romances with Roman elites, including whispers about connections with senators’ wives and even empresses, fueled both admiration and scandal. The allure didn’t end with their careers; connections to these warriors lasted well into their retirement and beyond.

The societal role of gladiators occasionally intersected with political ambitions, albeit discreetly. Unconfirmed tales suggest former gladiators sometimes held positions of influence, though these claims are often doubted. Nevertheless, gladiatorial combat and its participants remained a potent symbol of Roman ideals and excesses, deeply embedded in both myth and reality.

Meanwhile, retired gladiators pursued various paths. Some trained new fighters, leveraging their experience and increasing the ranks of skilled combatants. Others took on roles far removed from the violence of the arena. These transitions illustrate a complex interplay of social stigma and reluctant reverence, reflecting a culture that both glorified and marginalized its most dramatic entertainers.