Gaul

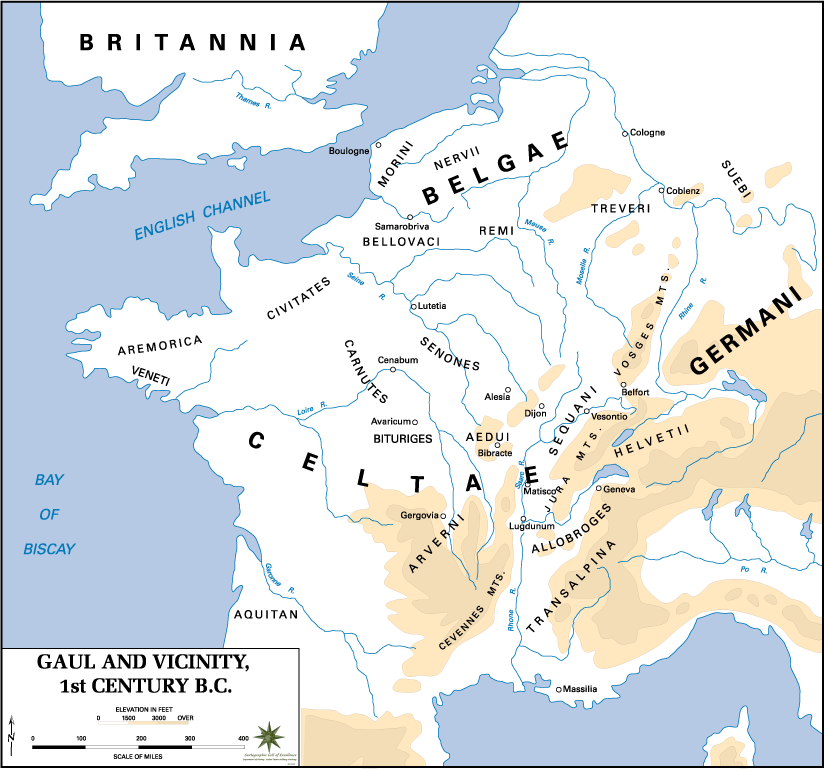

Gaul is an ancient geographical area that stretched from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Rhine River in the east, while it was bordered in the north by the North Sea, and in the south by the Pyrenees, the Mediterranean and the Po River valley, and was divided by the Romans into Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaul, which the Alps separated. Gaul was not a unified state, but a large number of tribes and peoples inhabited these areas. Gaul was divided into three parts, where the Aquitaniani, Belgae and Celts lived, whom the Romans called Gauls and who differed from each other in laws, customs and language.

The Gauls were engaged in agriculture and cattle breeding and had a completely different political life compared to the Romans. Among the Gauls, the horseback riders, who spent most of their lives in wars, and the druids, who were the religious representatives of the people who were the most educated, and did not pay taxes.

The rest of the people were without political influence and the vast majority of them fell under the protection of the powerful, under the burden of taxes. The Gallic tribes were not all at the same level of development, and there is a noticeable difference between the tribes that were closer to the Roman provinces and were much more developed than the tribes that had no contact with Roman culture.

Initial Conflicts

We do not know why Caesar chose Gaul as the province to govern, but we can assume that the choice of Gaul was another carefully thought-out part of Caesar’s plan to take power and influence in Rome. First of all, when Caesar went to Gaul, he took four legions with him, thus providing himself with military strength, and the recent past had shown that physical strength was the most important condition for strengthening the influence of an individual in Rome.

In addition, the conquest of Gaul would have opened up a great opportunity for Caesar to obtain wealth and conquer large areas that would be annexed to the republic. The interests of Julius Caesar as an individual and Rome as a state at that moment were identical, so Caesar waged the Gallic wars not for the triumvirs and the Senate, but for Rome and himself.

Before attacking the border tribes, Caesar needed a reason to leave the borders of Rome, and the migration of the Helvetii, which was thought to take place across Roman land, served as an excuse. When Caesar arrived at Geneva on the Rhone, envoys from the Helvetii arrived, seeking permission to cross Roman territory, but since Caesar denied them the opportunity to cross, they decided to take the more difficult route across the Seine to the lands of the Roman allies, the Aedui. The Aedui, as Roman allies, turned to Caesar for help, and Caesar was given an excuse for a military expedition.

Diviciacus, the brother of the Aedui leader, personally turned to Caesar for help, and this was enough for Caesar to prove that Rome’s interests were threatened. With the reasons for war thus prepared, Caesar set out and first defeated the Tigurini, who were part of the Helvetii tribal alliance, and then the Helvetii near Bibracte, thus protecting the Aedui. However, now there was a danger that the desolate Helvetian lands would be occupied by the Germans, which Caesar certainly had to prevent.

Ariovistus, the leader of the Suebi, who were considered friends of Rome, crossed the Rhine and began to threaten the Gallic tribes who were allies of Rome. A personal meeting between Caesar and Ariovistus in 58 BC did not lead to an agreement, so Caesar had to defeat the Suebi and throw them back across the Rhine. This war was much easier to justify, considering that the attacked Roman allies, the Aedui, who had asked Caesar for help. In these wars, Caesar showed his ability to motivate the army.

In 57 BC, Caesar’s legions fought the Belgae and Veneti, who were brought under the rule of the republic, although he did not personally lead the army, since he was in Illyricum and the area around the Po River at the time.

The Uprising in Gaul

After the meeting in Lucca, Caesar continued with campaigns that he could no longer be justified by defending Roman allies. He was driven to these new campaigns by adventurism and, above all, by the desire for spoils of war and glory. In 55 BC, Caesar was the first to cross the Rhine River, building a bridge in just ten days. In the same year, the first attempt to land in Britain was unsuccessful due to the sea winds, the unsuitability of Roman ships, the high cliffs on the coast near present-day Dover, and the hostility of the natives.

The following year, after a short trip to Illyricum, Caesar embarked on a new campaign against Britain. This time, Caesar used the same strategy with allies as in Gaul and had much more success in finding tribes who feared the ruler there. In his second campaign, Caesar reached the Thames River before returning to Gaul for the winter, and then received three legions from Pompey that had been recruited in Gaul.

The next year, in 53 BC, while Caesar was in Rome, the largest rebellion in Gaul occurred under the leadership of Vercingetorix of Gergovia. He managed to win over many tribes to his cause. When he learned of the rebellion, Caesar set out from northern Italy to meet the rebels. Even the Aedui tribe, a former loyal ally of the Romans, approached Vercingetorix in his war on Caesar. Caesar was separated from his army, which had wintered in Gaul. Vercingetorix set out to meet Caesar, who had managed to break through to his two legions near the land of the Arverni.

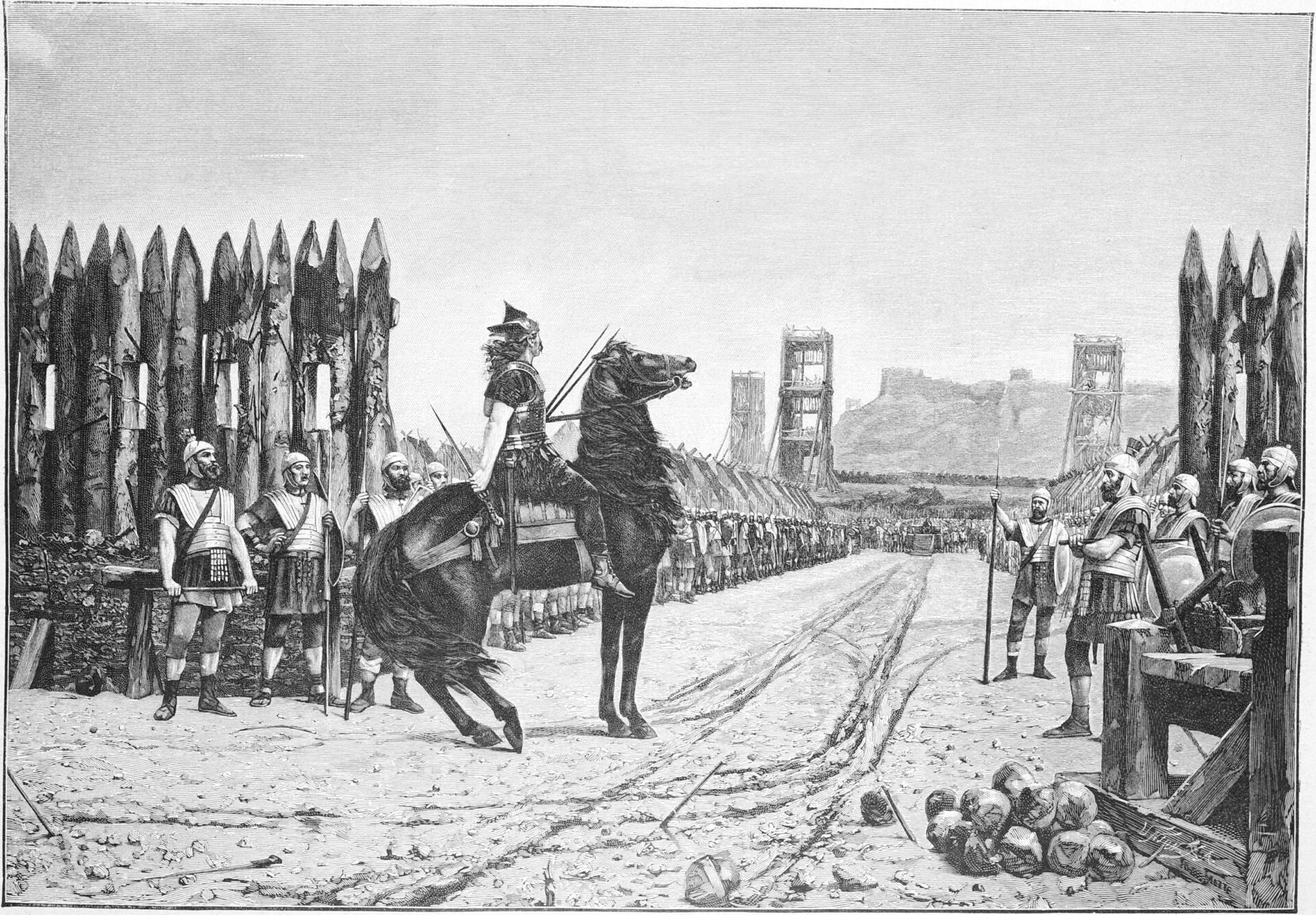

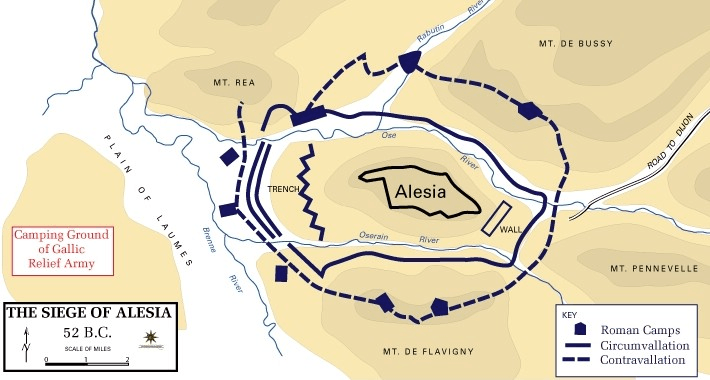

In the first battles of Avaricum and Dijon, Caesar won, but had a major problem with supplies because Vercingetorix used scorched earth tactics. The decisive battle took place during the siege of Alesia, a fortress where the Gauls and their leader were taking refuge. Plutarch claims that the Gauls numbered 470,000, which is certainly not a realistic estimate. Through a systematic siege, Caesar forced the Gauls to surrender after they ran out of supplies and began to starve. Their leader, Vercingetorix, emerged from the main gate of the fortress in armor and personally surrendered to Caesar in order to save his people.

Vercingetorix was executed in 46 BC on the night after Caesar’s triumph. All of Gaul was under Roman rule and pacified after 51 BC when occasional uprisings ceased. Tribal leaders received gifts from Rome, and in return they maintained Roman rule, while Roman troops were stationed only in certain parts. Caesar ended the conquest of Gaul as a wealthy man and equal in military glory to Pompey.

Sources and Literature:

Appianus, of Alexandria. (1902). Appianou Romaikon Emphylion A = Appian, Civil Wars, book I. Oxford: Clarendon Press,

Morey, W. C. (1900). Outlines of Roman history: For the Use of High Schools and Academies.

Caesar, Julius. (1953). War commentaries: De bello Gallico and De bello civili. London: New York: Dent; Dutton,

Plutarch. (1859). Plutarch’s Lives: translated from the original Greek, with notes, critical and historical, and life of Plutarch. New York: Derby & Jackson,

Hello, my name is Vladimir, and I am a part of the Roman-empire writing team.

I am a historian, and history is an integral part of my life.

To be honest, while I was in school, I didn’t like history so how did I end up studying it? Well, for that, I have to thank history-based strategy PC games. Thank you so much, Europa Universalis IV, and thank you, Medieval Total War.

Since games made me fall in love with history, I completed bachelor studies at Filozofski Fakultet Niš, a part of the University of Niš. My bachelor’s thesis was about Julis Caesar. Soon, I completed my master’s studies at the same university.

For years now, I have been working as a teacher in a local elementary school, but my passion for writing isn’t fulfilled, so I decided to pursue that ambition online. There were a few gigs, but most of them were not history-related.

Then I stumbled upon roman-empire.com, and now I am a part of something bigger. No, I am not a part of the ancient Roman Empire but of a creative writing team where I have the freedom to write about whatever I want. Yes, even about Star Wars. Stay tuned for that.

Anyway, I am better at writing about Rome than writing about me. But if you would like to contact me for any reason, you can do it at contact@roman-empire.net. Except for negative reviews, of course. 😀

Kind regards,

Vladimir