The Civil War – Caesar in Italy

The civil war had begun, and Pompey was in Rome. The consuls authorized Pompey to take command of the two legions stationed in Capua to defend Rome from a possible attack by Caesar. Pompey was then authorized to gather 130,000 soldiers. Caesar also had two legions with him in Ravenna, a total of about 5,000 soldiers and 300 cavalry. Caesar decided to strike quickly with a smaller military force, believing that it would be easier to achieve victory than later with a larger army, but also with Pompey prepared. He was certainly right, since Pompey failed to gather an army in time.

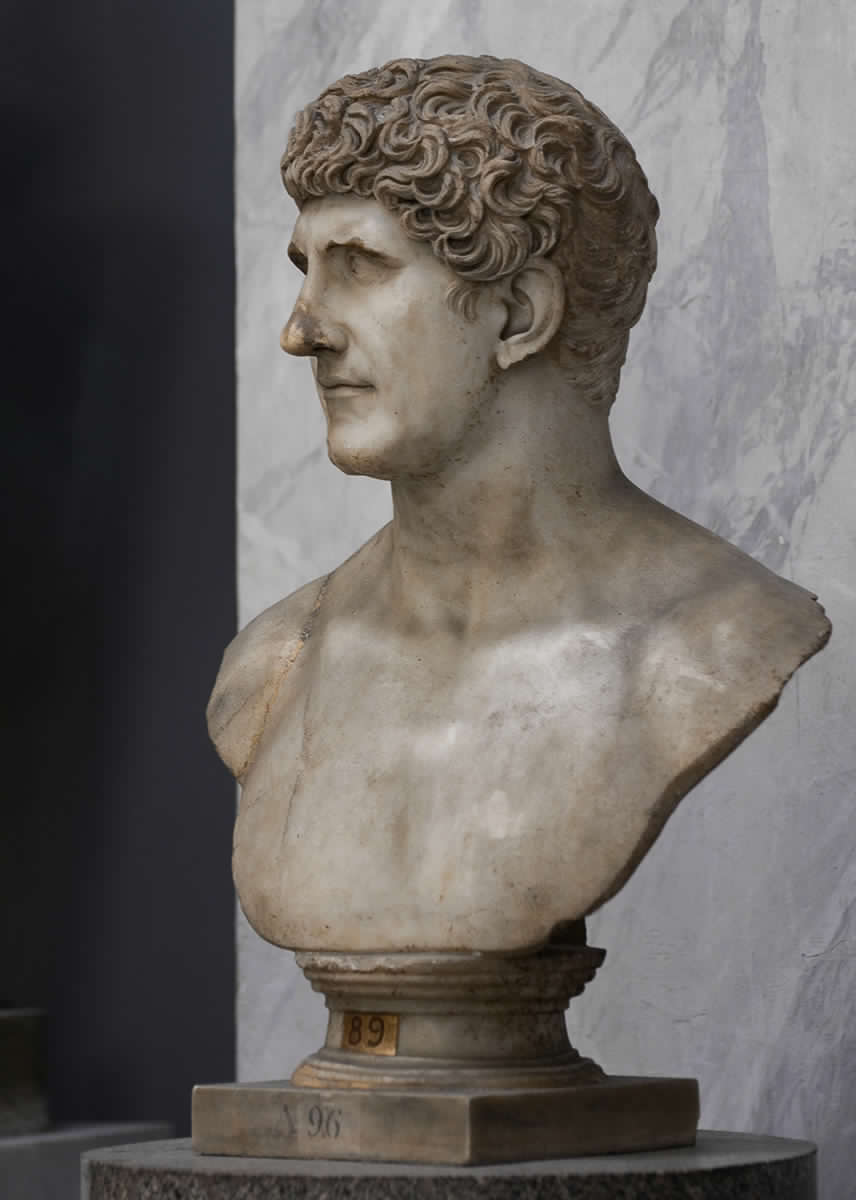

A few days before his departure, Mark Antony, as the tribune of the people, requested a halt to the recruitment of the army and the transfer of the legions to the East due to the war with the Parthians, which gave Caesar enough time to gain a great advantage in military terms. After much deliberation, Caesar crossed the Rubicon River on the night of January 10–11, which separated his province from the rest of Italy, thus beginning the civil war. On the same day that he crossed the Rubicon, Caesar already had the city of Ariminum (today’s Rimini) under his control. Caesar moved through Italy without much trouble, and cities such as Ancona and Aretium opened their gates to him.

During this time, Pompey left Rome on January 18, 49 BC, as he was separated from his army in Hispania. Pompey was criticized from all sides, some for not being able to reach an agreement with Caesar, and others for elevating Caesar. Cicero unsuccessfully tried to mediate between the two warring parties and then joined Pompey. When Pompey left the city, he called with him all the people who were against tyranny and repeated that the state is made of the people, not the city.

The first resistance to Caesar was offered by Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, an old enemy, consul in 54 BC and Caesar’s planned replacement in Gaul at the Battle of Corfinium. He was not a military leader who would be a worthy opponent to Caesar, and in addition, part of his army had gone over to Caesar’s side, so he had no chance of success, and after a failed suicide attempt, he surrendered to Caesar. Caesar was kind and, after taking away his command of the army, he let him go along with his son and money, and Lucius Domitius immediately went back to Pompey.

Caesar’s treatment of the prisoners quickly gained a good reputation, so many refugees returned to Rome, which proved to be an excellent strategy. Caesar showed that he was neither Marius nor Sulla, that he was simply achieving his military goals and was not trying to take revenge and punish them, which brought him even more supporters. Caesar set off in pursuit of Pompey’s army, which was in Brindisi, but Pompey managed to escape on March 17 across the Adriatic Sea to Epirus.

Pompey had to leave Italy since Caesar had an army, and his army was in Hispania and the East. The plan was for Pompey’s army to regroup in the Balkans, from where a victorious landing in Italy would follow, since Pompey had an undeniable advantage at sea. Caesar triumphantly entered Rome itself and tried to find a candidate to offer negotiations to Pompey, but Caesar’s problem was that the senators who remained in the city were considered traitors by those who had fled, so, in fear for their lives, no one wanted to go to Pompey as Caesar’s representative.

Caesar in Spain

Caesar confiscated the money he found in the city, which was met with objections from the people’s tribune Metellus. Then, Metellus was explained that this is a time of war and that he is on the opposing side, so that his position has no importance for Caesar. He is also told that it would be best for him to stop protesting for the sake of his own safety. After leaving Rome, Caesar does not move with his army to meet Pompey’s army in Epirus, but to Hispania, where Pompey’s legions are located.

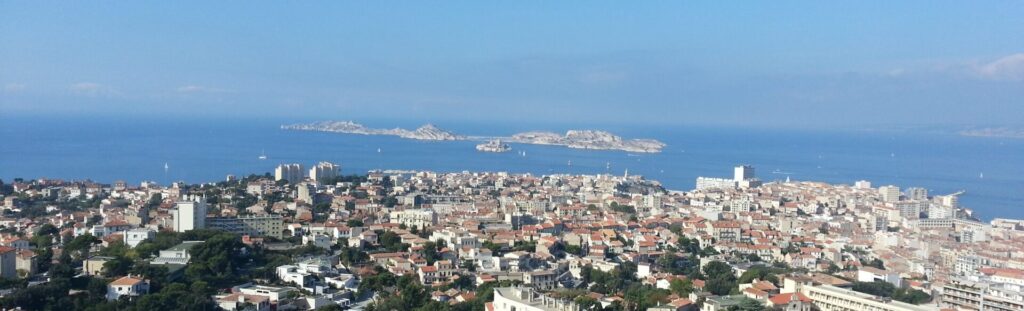

While passing through Spain, he left part of the army under siege at Massilia (modern Marseilles), which had been captured while he was fighting in Hispania. Arriving there, he encountered the same old problems of supplying the army that he had also faced in the Gallic Wars. Pompey’s legions in Hispania were under the command of Lucius Afranius and Terentius Varro. The weather was not in Caesar’s favor either, as the Ilerda River flooded and cut off his army from its supply lines. However, here too, some legions switched sides, making Caesar’s job easier. After 40 days, Caesar’s campaign in Hispania was successfully concluded, and Pompey’s rule in this province no longer existed.

The Defeat in Africa

Meanwhile, in Africa, the young Curio recklessly entered the battle unprepared, which cost him defeat and his life. Namely, at the Bagradas River, Curio believed the news that Pompey’s ally, the Numidian king Juba, had retreated and that only a small part of the army under his command remained. Curio led the army on a march across the desert in the hot afternoon sun. When the armies met, Curio found out that the information was incorrect, and Juba saw the deplorable state of the soldiers under the command of Curio, who did not even have access to water during the march.

Curio recklessly led the army to the plain near the river itself, where they were quickly surrounded. Part of the army managed to fight their way back to the hills, while Curio’s head ended up on a spear as a trophy of King Juba, who hated Curio because it was Curio, as a tribune, who proposed the confiscation of Juba’s kingdom.

The rest of the army, after an unsuccessful attempt to escape by merchant ships, surrendered to Pompey’s commander Attius Varus. They were also executed by King Juba, despite Varus’s objections. Caesar was greatly affected by the news of Curio’s death, for whom he claims that he did not want to return alive without the army that Caesar had entrusted to him, but that he would fight to be killed.

The Intense Situation

After the first year of the war, Caesar ruled Italy and Hispania, while Pompey ruled the East, Africa, and the seas. Caesar’s surprise attack with a small army did more than give his opponents a chance to prepare. In January 48 BC, Caesar crossed the Adriatic Sea with 5 legions and 600 cavalry.

His army was slow to assemble in Brindisi, so he decided to cross the sea with such a small number of soldiers, and he also took advantage of the element of surprise, since Caesar appeared on the other side of the Adriatic before news of his crossing reached the Pompeian camps. It is believed that the army was slow to assemble because they were tired of fighting, but they felt humiliated when they learned that they had been left behind, so morale immediately rose.

After crossing the Adriatic, Caesar took advantage of Pompey’s proximity to Lake Ohrid and quickly conquered the places near the Epirus coast. Caesar then offered a truce under which both sides would disband their armies and let the Senate decide their fate, which was the same as what had once been offered to Caesar, only now Caesar had filled the Senate with his supporters, and it would not be difficult to guess who would get all the power.

This was an excellent situation for Caesar, since he had sent an unacceptable proposal to Pompey, and presented himself as someone who only wanted peace and law. However, despite the promise of safety, Caesar’s legate Vatinius was attacked by the Pompeians with messages that there would be no peace as long as Caesar was alive.

Caesar had a much smaller army than Pompey, and reinforcements never arrived since Pompey’s fleet controlled the sea, and even Caesar himself, admittedly unsuccessfully, tried to cross to Italy under cover of night to speed up preparations for the transfer of the army. After three months, troops under the command of Mark Antony finally arrived, so that Caesar’s army was now larger than Pompey’s, but Caesar’s old problem with supplying the army was most pronounced right now.

He was pressed from the sea, and he did not have enough troops for a frontal duel with Pompey until Mark Antony arrived. Plutarch claims that the army ate some roots that grew in the area and made bread from them, which led to various diseases among the soldiers, but also created fear in the opposing side, who had the impression that they were fighting beasts, not people.

Sources and Literature:

Appianus, of Alexandria. (1902). Appianou Romaikon Emphylion A = Appian, Civil Wars, book I. Oxford: Clarendon Press,

The Cambridge Ancient History IX (2008),

Beard, M. (2015). SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome.

Caesar, Julius. (1953). War commentaries: De bello Gallico and De bello civili. London: New York: Dent; Dutton,

Plutarch. (1859). Plutarch’s Lives: translated from the original Greek, with notes, critical and historical, and life of Plutarch. New York: Derby & Jackson,

Morey, W. C. (1900). Outlines of Roman history: For the Use of High Schools and Academies,

Hello, my name is Vladimir, and I am a part of the Roman-empire writing team.

I am a historian, and history is an integral part of my life.

To be honest, while I was in school, I didn’t like history so how did I end up studying it? Well, for that, I have to thank history-based strategy PC games. Thank you so much, Europa Universalis IV, and thank you, Medieval Total War.

Since games made me fall in love with history, I completed bachelor studies at Filozofski Fakultet Niš, a part of the University of Niš. My bachelor’s thesis was about Julis Caesar. Soon, I completed my master’s studies at the same university.

For years now, I have been working as a teacher in a local elementary school, but my passion for writing isn’t fulfilled, so I decided to pursue that ambition online. There were a few gigs, but most of them were not history-related.

Then I stumbled upon roman-empire.com, and now I am a part of something bigger. No, I am not a part of the ancient Roman Empire but of a creative writing team where I have the freedom to write about whatever I want. Yes, even about Star Wars. Stay tuned for that.

Anyway, I am better at writing about Rome than writing about me. But if you would like to contact me for any reason, you can do it at contact@roman-empire.net. Except for negative reviews, of course. 😀

Kind regards,

Vladimir