The history of Rome is filled with grandeur and cultural achievements that have left a significant imprint on the world. Even after its fall, numerous kingdoms and empires aimed to inherit this legacy. Various groups sought to connect themselves to the Roman culture, infusing it with their own traditions, and using Roman titles and symbols to bolster their authority, blending Roman legacies with their evolving identities.

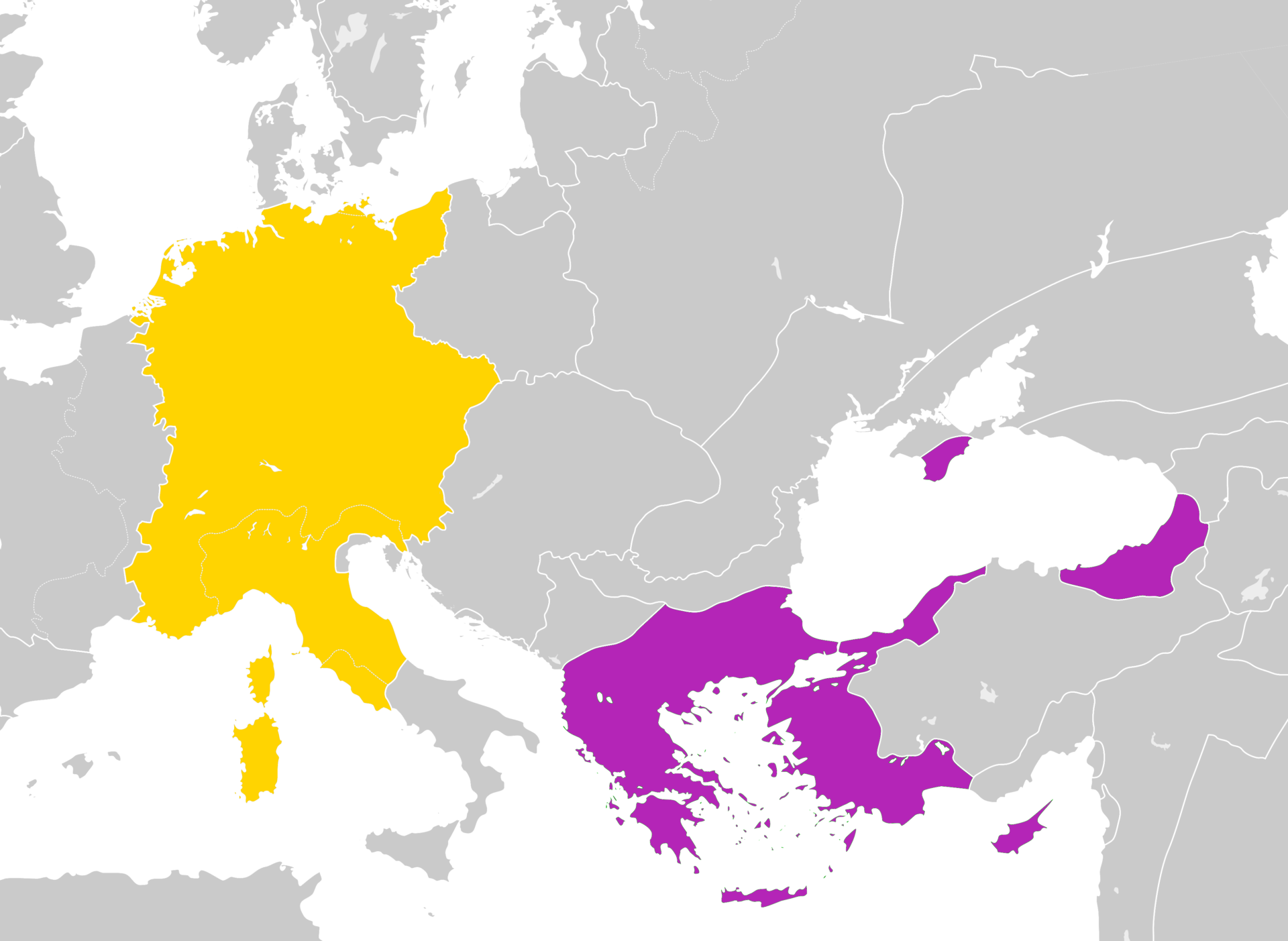

With the division of the Roman Empire in 395 CE, new powers emerged. In the West, kingdoms like the Franks embraced Roman influences while asserting their independence. Across Europe and the Mediterranean, claims to the Roman legacy varied. The medieval period saw three main contenders: Byzantium, the Holy Roman Empire, and the Vatican, each asserting itself as a true continuation of Roman traditions in its own way. This video explores the evolving concept of Romanness and the question of Rome’s true heir.

Key Takeaways

- Various groups sought to inherit the Roman legacy.

- Byzantium, the Holy Roman Empire, and the Vatican were main contenders.

- The evolution of Romanness varied across regions.

Celts, Franks, and Merovingians

The Western Empire’s Split and Fall

In 395 CE, the Roman Empire was divided into two parts following Emperor Theodosius’s death. His sons took charge, with Honorius overseeing the Western part and Arcadius ruling the East. The Western half faced numerous invasions by tribes such as the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, and Vandals in the 5th century CE, leading to its eventual disintegration.

Emergence of New Kingdoms After Rome

After the decline of the Western Roman Empire, kingdoms emerged in these regions. Among them, the Merovingian dynasty held sway over the Frankish Kingdom in former Roman territories like Gaul. These kingdoms didn’t abandon Latin entirely. Instead, they used Latin in church and government, integrating it into their lives for many years.

Connections to Rome

Many of these emerging kingdoms sought ties to the once-great Roman Empire to reinforce their power. Some created genealogies linking themselves to Roman figures. Irish Gaelic writings even suggested that the Irish and Welsh descended from Trojans, similar to Roman claims. The Franks appeared in these stories too, portrayed as Roman cousins from Trojan roots. Yet, the origin of these tales remains uncertain.

Merovingians and the Roman Legacy

The Merovingian Dynasty had a complex relationship with Roman history. They sometimes claimed connections to Trojans or Roman senators. Yet, real relations with other nobles were more important to them than ancient Roman ties. Although there was no consistent effort to inherit the Roman legacy, these early states used Roman government methods, law, and language.

Language and Culture Persisting in the West

Latin evolved into the Romance languages we recognize today. This transformation illustrates how Roman culture and language continued in parts of Europe like France, Iberia, Italy, and the Balkans. This legacy exists due to Roman influence in the Mediterranean and the Catholic Church’s use of Latin across the region.

Holy Roman Empire, Vatican, and Byzantium

Legacy of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, carried on Roman traditions in law and administration after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Constantinople, founded by Emperor Constantine, reflected Roman architectural brilliance with landmarks like the Hippodrome. Over time, as the empire embraced Christianity, being Roman became intertwined with being a Chalcedonian Christian. Greek influence increased, but the Byzantine Empire maintained its Roman legal roots. This Hellenized form led to some friction with the Vatican over ecclesiastical influence and authority.

Vatican’s Religious Authority

The Vatican emerged as a key player in claiming the Roman legacy. Initially under Byzantine influence, the Vatican began to assert more independence, refusing attempts by Byzantine emperors to control Church practices, such as during the Iconoclasm controversy. The concept of Papal primacy, which placed the Pope above other church leaders, gained traction. This led to the Pope’s endorsement of Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor, signifying the Vatican’s break from Byzantine control and its claim to Roman heritage.

The Claims of the Holy Roman Empire

Charlemagne’s coronation as Holy Roman Emperor in 800 CE marked the beginning of the Holy Roman Empire’s claim to the Roman legacy. Supported by the Pope, this empire used its Christian foundations and Latin-speaking institutions to stake its claim. Despite its diverse ethnic makeup, the Holy Roman Empire’s association with the Roman church and its divine sanction bolstered its position as an heir to Rome.

Interaction Between Byzantium, Vatican, and Holy Roman Empire

All three entities—Byzantine Empire, Vatican, and Holy Roman Empire—vied for the title of being Rome’s true successor. Byzantium relied on its uninterrupted Roman and legal continuity, while the Vatican emphasized its religious heritage tied to Rome’s historic church foundations. The Holy Roman Empire, meanwhile, leveraged Papal approval and its governance structure to assert its claim. Each maintained a distinct identity, often leading to diplomatic tensions.

Theological Disputes and Division

Religious disputes heightened the rivalry among these heirs. The Vatican emphasized Papal supremacy and theological dominance. In contrast, Byzantines rejected Rome’s theological superiority, advocating for their patriarch’s equality. These tensions culminated in the great Schism of 1054, splitting Christianity into the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches.

The Conflict Over Roman Imperial Titles

The dispute over who deserved the Roman Emperor title, known as the “Problem of Two Emperors,” fueled much contention. Both the Byzantine and Holy Roman Empires claimed this title, as it symbolized universal authority in Christendom. As each fiercely defended their claim, this issue persisted across the Middle Ages, causing frequent diplomatic conflicts.