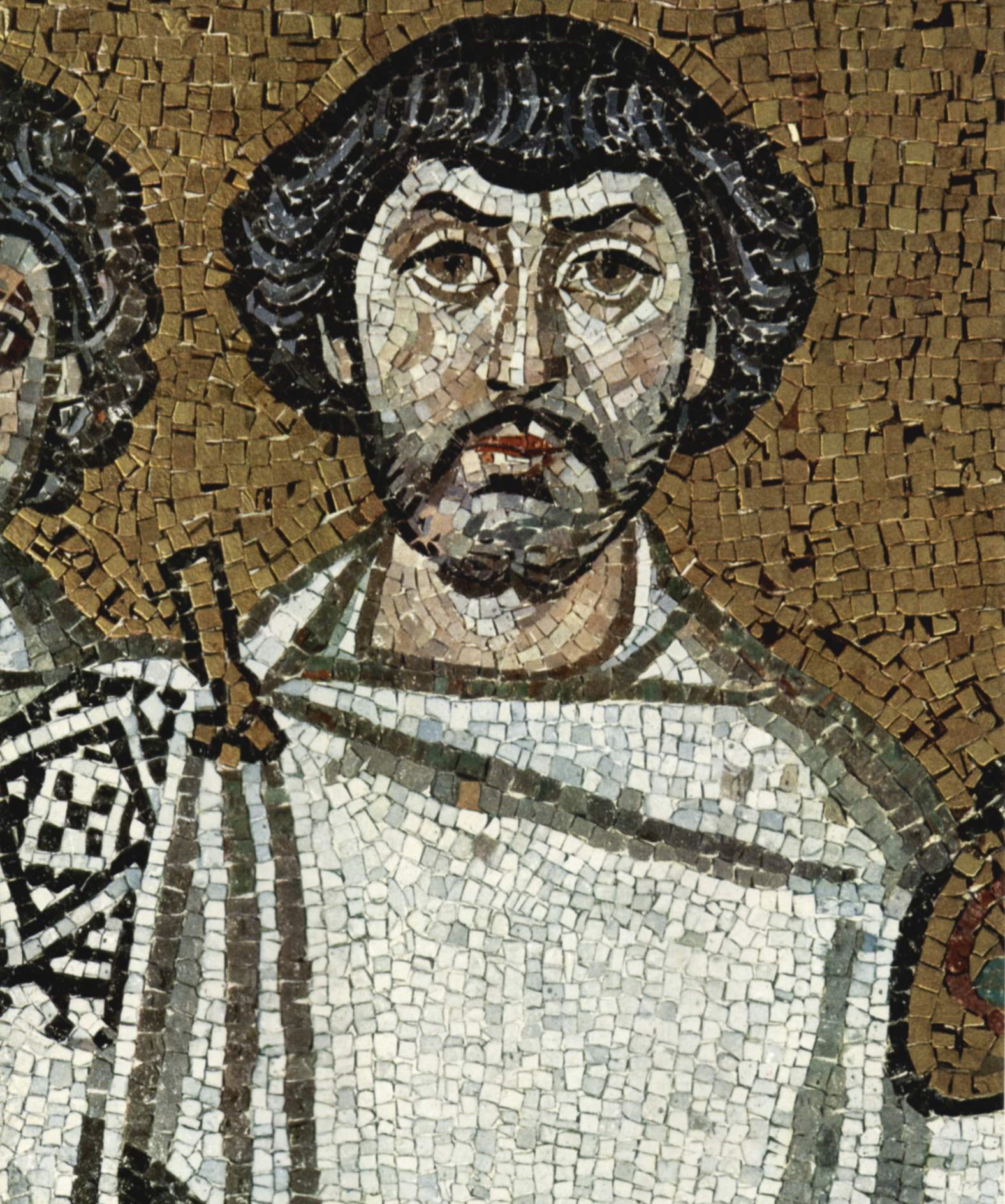

Belisarius is considered one of the most remarkable military commanders in history. He was a man who commanded the army and fought to restore the glory of Rome when most of the empire was already gone. Serving under Emperor Justinian I in the 6th century, he won battles from the deserts of Persia to the plains of Italy. He crushed enemies far stronger in number, yet died without the wealth or power his victories might have earned him.

Early Life and Rise to Command

Belisarius was born around 500 AD, between 500 and 505, most likely in Thrace or Illyria. At that time, these were the frontier lands of the Eastern Roman Empire. There, military life was part of the daily existence. Little is known of his family, but he joined the imperial guard as a young man, serving under Emperor Justin I, Justinian’s uncle.

Early in his career, he developed a personal unit of heavy cavalry, the bucellarii, equipped with composite bows and lances. This elite force would become the backbone of his campaigns. By his late twenties, Belisarius had earned Justinian’s trust and was entrusted with important commands on the empire’s eastern frontier.

The Persian Campaigns – A Commander Emerges

The Eastern Roman Empire’s most dangerous enemy in the early 6th century was the Sassanian Persian Empire. In 530 AD, Belisarius, still a young general, faced a much larger Persian army at the Battle of Dara. Using trenches, fortifications, and cavalry maneuvers, he inflicted a decisive defeat on the Persians, a rare victory in a long, draining war.

The following year, however, he suffered a setback at Callinicum, where the Persians forced him to retreat. Although the defeat was not catastrophic, it taught him caution and the limits of fighting on unfavorable ground. Soon after, a treaty known as the “Eternal Peace” was signed in 532, giving the Eastern Empire a momentary respite.

The Nika Riots – Saving Justinian’s Throne

Peace abroad did not mean peace at home. In January 532, Constantinople erupted into chaos during the Nika Riots, sparked by a dispute over chariot racing factions but quickly turning into a political revolt against Justinian.

Belisarius, alongside the court official Narses, led a counterattack into the Hippodrome where tens of thousands of rebels had gathered. The imperial troops massacred the rioters, with later accounts estimating some 30,000 dead. The brutality of the suppression preserved Justinian’s rule, and Belisarius emerged as the emperor’s most dependable servant.

The Vandalic War – Reconquest of North Africa

Justinian’s vision of restoring the Roman Empire began with the wealthy provinces of North Africa, lost to the Vandals a century earlier. In 533, Belisarius sailed with about 15.000 men, which was a modest force by ancient standards, to Carthage.

At the Battle of Ad Decimum, he outmaneuvered the Vandal king Gelimer despite being heavily outnumbered. Days later, at Tricamarum, Belisarius struck again, breaking Vandal resistance. Carthage was retaken, and the Vandal kingdom collapsed. Gelimer surrendered in early 534, and Africa returned to imperial hands without the prolonged war many had expected. The speed of the campaign stunned contemporaries.

The Gothic War – Triumph and Betrayal in Italy

The next target was the Ostrogothic Kingdom in Italy. In 535, Belisarius led an invasion that quickly seized Sicily before advancing into the Italian mainland. Naples fell after a clever infiltration of the city’s aqueduct, and by December 536, Belisarius entered Rome.

The Ostrogothic king Witiges laid siege to the city in 537–538, but Belisarius’s defensive tactics, including the use of cavalry raids to disrupt supply lines, forced the Goths to retreat. The campaign culminated in the capture of Ravenna in 540. Astonishingly, the Goths offered Belisarius the Western imperial crown, which he refused, feigning acceptance only to deliver Ravenna to Justinian.

Instead of gratitude, he returned to Constantinople under a cloud of suspicion. His growing fame had alarmed the emperor and Empress Theodora, and court rivals whispered of ambition and disloyalty.

Later Campaigns – From Glory to Frustration

In 541, Belisarius was sent east again to face the Persians. Success was limited, as plague and politics hampered operations. Soon after, he was recalled to Italy in 544 to confront the Ostrogothic king Totila.

This second Italian campaign was far harder. Belisarius was given insufficient troops and supplies, and imperial strategy was indecisive. He managed to hold key cities like Rome for a time but could not decisively defeat Totila. Exhausted and frustrated, he was recalled in 549.

A final flash of brilliance came in 559, when a force of Kutrigur Bulgars crossed the Danube and threatened Constantinople. With only a handful of men, Belisarius bluffed and maneuvered them into retreat — a last reminder of his tactical genius.

Political Intrigue and Downfall

Belisarius’s military successes never shielded him from the intrigues of the imperial court. His relationship with Narses was tense, and Theodora viewed him with suspicion. In 562, he was accused of corruption, likely a politically motivated charge.

He was briefly imprisoned and stripped of command. Although Justinian eventually pardoned him, the episode tarnished his final years. A later legend claimed he was blinded and forced to beg in the streets of Constantinople, crying, “Give an obol to Belisarius!” Modern historians agree this story is almost certainly apocryphal, invented centuries later to illustrate the ingratitude of rulers.

Death and Legacy

Belisarius died around 565 AD, only months before Justinian. He left no great fortune, no dynasty, and no political power. What he did leave was a record of victories unmatched by any other general of the late Roman Empire.

Our main source for his life, the historian Procopius, offers two contrasting portraits: the loyal, capable commander in the Wars and the bitter, scandal-filled portrayal in the Secret History. The truth likely lies between the extremes. He was a gifted soldier, loyal to a fault, who navigated the treacherous politics of Justinian’s reign.

In later centuries, Belisarius became a romantic figure. Painters in the 18th century depicted him as the “blind beggar general,” while novelists used his life to explore themes of loyalty, betrayal, and the collapse of empires.

Hello, my name is Vladimir, and I am a part of the Roman-empire writing team.

I am a historian, and history is an integral part of my life.

To be honest, while I was in school, I didn’t like history so how did I end up studying it? Well, for that, I have to thank history-based strategy PC games. Thank you so much, Europa Universalis IV, and thank you, Medieval Total War.

Since games made me fall in love with history, I completed bachelor studies at Filozofski Fakultet Niš, a part of the University of Niš. My bachelor’s thesis was about Julis Caesar. Soon, I completed my master’s studies at the same university.

For years now, I have been working as a teacher in a local elementary school, but my passion for writing isn’t fulfilled, so I decided to pursue that ambition online. There were a few gigs, but most of them were not history-related.

Then I stumbled upon roman-empire.com, and now I am a part of something bigger. No, I am not a part of the ancient Roman Empire but of a creative writing team where I have the freedom to write about whatever I want. Yes, even about Star Wars. Stay tuned for that.

Anyway, I am better at writing about Rome than writing about me. But if you would like to contact me for any reason, you can do it at contact@roman-empire.net. Except for negative reviews, of course. 😀

Kind regards,

Vladimir