During the First Punic War, Rome and Carthage clashed in a massive naval battle near Ecnomus. With hundreds of warships and almost 300,000 men involved, this fight stands out as one of the largest naval engagements in history. Both sides pushed their resources to the limit, using new tactics and ship designs in hopes of gaining an edge.

The stakes were high as Rome aimed to invade North Africa, while Carthage gathered its largest fleet yet to stop them. Leadership decisions, ship formations, and innovative weapons played key roles in shaping the course and outcome of the battle.

Key Takeaways

- The clash at Ecnomus featured huge fleets and marked a major event in the First Punic War.

- Both sides used new naval tactics and technologies to try to gain an advantage.

- The outcome influenced future naval warfare and left a strong historical legacy.

Summary of the Battle at Ecnomus

Importance in Ancient History

The naval conflict at Ecnomus marked a major event during the First Punic War between Rome and Carthage. This fight was key because both powers were trying to control the Mediterranean Sea and, more importantly, the island of Sicily. The battle signaled Rome’s rise in naval warfare, even though they had far less experience than Carthage.

Both Roman consuls, Lucius Manlius and Marcus Atilius Regulus, took command during the battle, showing how crucial it was for Rome. Carthage also sent top leaders to face the threat. Their goal was nothing less than to halt Rome’s invasion of North Africa. The tactics at play, such as the use of boarding bridges called corvi by the Romans and the careful formations used by both sides, reflected how both sides adapted to new forms of naval warfare.

Numbers and Scale of the Engagement

The meeting at Ecnomus is often listed among the largest naval battles in ancient history—if not the largest.

- Roman fleet: 330 warships

- Carthaginian fleet: 350 warships

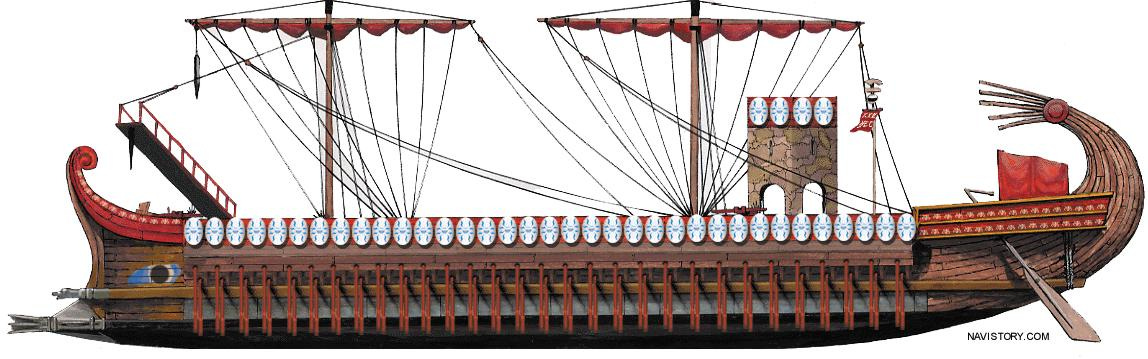

Estimates suggest as many as 290,000 people took part, including rowers and marines. The ships in this clash were mostly “fives” (quinqueremes), each around 40 meters long and holding about 300 rowers with 120 marines per ship.

Here is a simple table comparing Ecnomus to other major sea battles:

| Battle | Number of Warships | Personnel Involved |

|---|---|---|

| Ecnomus | 680 | 290,000 |

| Salamis | Approx. 680 | 200,000 |

| Lepanto | 484 | 150,000 |

| Spanish Armada (1588) | 330 | — |

| Jutland (WWI) | 250 | 100,000 |

| Leyte Gulf (WWII) | 367 | 200,000 |

Both scale and planning at Ecnomus set a standard that would rarely be matched, even by later battles centuries into the future. The packed formations, the numbers involved, and the leadership present all showed the importance both sides placed on this confrontation.

Strategic Factors Behind the Outbreak of the First Punic War

Underlying Reasons for Hostilities

In 264 BC, Sicily became the focal point of rising tensions as mercenary groups stirred unrest. This instability drew the attention of Rome and Carthage, both eager to secure influence over the island. Their involvement in Sicily was not a result of long-standing rivalry, but rather a reaction to new opportunities and threats caused by local conflicts.

The situation escalated rapidly. What began as a localized dispute soon turned into a prolonged and bloody war that lasted 23 years. Both powers deployed significant land and naval forces, each seeking to tip the balance in their favor.

Mediterranean Power Dynamics

At the start of the conflict, Rome had only recently finished securing southern Italy. Carthage, in contrast, already held extensive territories, including parts of North Africa, Spain, Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica, as well as other Mediterranean islands.

Control of Sicily was especially important. The island acted as a central hub for trade and military movements in the region. Whoever controlled Sicily could potentially dominate the surrounding trade routes and supply lines. The two sides committed enormous resources, with ever-larger fleets and innovative technology such as the Roman corvis boarding bridge.

Key Mediterranean Stakeholders During the First Punic War:

| Power | Main Territories | Military Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Rome | Italy | Strong land armies |

| Carthage | North Africa, Spain, islands | Powerful navy |

Both Rome and Carthage understood the value of naval supremacy to maintain and expand their influence. This strategic competition over Sicily and regional dominance set the stage for major engagements like the massive naval showdown at Ecomis.

Seaborne Warfare and New Ideas

Growth of Rome’s Warships

Rome was not always a powerful navy. At first, Carthage controlled the seas while Rome was known for its strong land army. As their battles spilled into Sicily, Rome struggled with Carthage’s grip on supply routes and troop movements.

To change this, Rome built a fleet of around 120 warships. They moved quickly to match Carthage’s naval force and keep their own army supplied. As the conflict grew, both sides put great effort and resources into building even more ships.

The table below shows the approximate size of major fleets in important battles:

| Battle | Year | Warships | Personnel |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eomis | 256 BC | 680 | 290,000 |

| Salamis | 480 BC | similar | 200,000 |

| Lepanto | 1571 AD | 484 | 150,000 |

| Spanish Armada | 1588 AD | 330 | N/A |

| Jutland | 1916 AD | 250 | 100,000 |

| Leyte Gulf | 1944 AD | 367 | 200,000 |

Carthage had a long tradition of skill at sea. Their ships were fast, with skilled crews. In battles, Carthaginian fleets used advanced tactics like ramming enemy vessels, maneuvering for the best position, and striking at exposed sides.

At the Battle of Eomis, Carthage organized its fleet into a wide front, using most “fives”—ships manned by about 300 rowers and 120 marines. Their ships moved in lines and aimed to break enemy formations and strike from the flanks or rear. Carthaginian leaders were careful fighters and looked for weaknesses in the enemy’s tactics.

Key Carthaginian battle strategies:

- Overlapping the enemy on the wings

- Thinning out the center to draw enemies in

- Using speed and superior ramming skills

The Roman Boarding Bridge (Corvus)

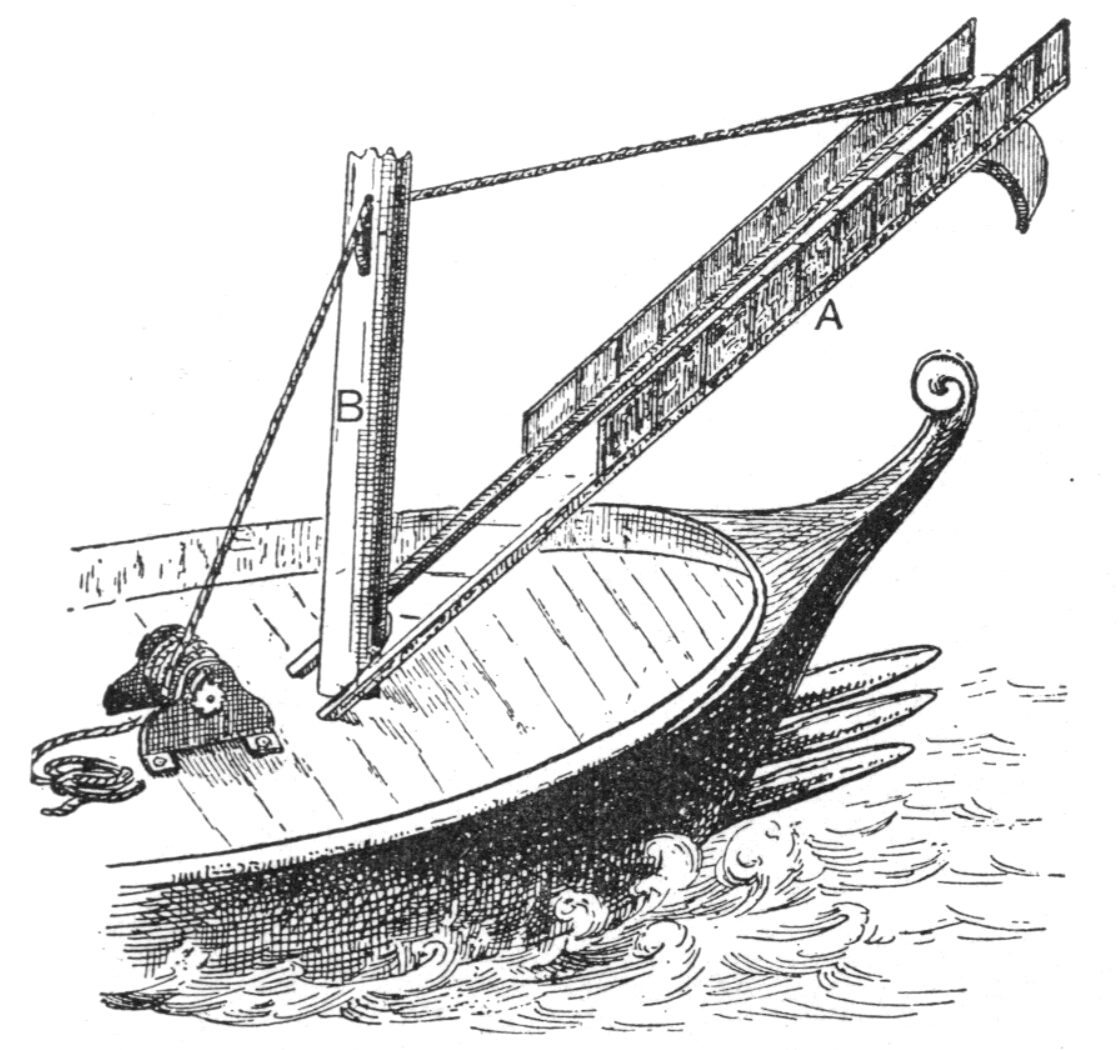

Unable to win in classic sea battles, Rome brought a new tool to the sea: the corvus—or boarding bridge. This device was a tall, swiveling plank with a spike at its end. When two ships came close, Romans dropped the corvus onto the enemy ship and used it as a bridge to send soldiers across.

This shifted battles from ramming and quick movement into close combat, playing to Rome’s strength in infantry fighting. The corvus helped Rome stand toe-to-toe with Carthage even though their sailors were less experienced.

Features of the corvus:

- Metal spike to anchor onto enemy ships

- Allowed Roman marines to board quickly

- Helped close the gap between land and naval fighting styles

The corvus changed the focus of battles at sea, letting Rome turn Carthaginian strengths against them.

Fleet Composition and Tactics

Types of Warships and Their Features

Both the Roman and Carthaginian fleets relied on large warships during the battle. Most vessels were known as “fives,” about 40 meters long and 5 meters wide. Each one held close to 300 rowers and around 120 marines. Some smaller ships and a few larger flagships also took part in the battle.

| Ship Type | Approx. Length | Rowers | Marines | Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quinquereme (Five) | 40 m | 300 | 120 | Standard warship |

| Trireme (Three) | Smaller | Fewer | Fewer | Light craft |

| Hexareme (Six) | Larger | More | More | Flagship/command ship |

Ships were built for speed and could move quickly across the sea. The main tactic at the time was ramming, using strong hulls and sharp prows to smash into enemy ships and break their oars or even rip open their sides.

Roman Fleet Arrangement and Battle Approach

The Roman fleet was new to sea warfare and used innovative ideas to gain an advantage. They equipped their ships with the corvus, a boarding bridge with a heavy spike, turning sea battles into hand-to-hand fights where Roman soldiers could win.

Romans organized their fleet into four groups:

- The lead groups, each under one consul, formed the front point of a triangle.

- These first units were followed closely by more ships, staggered on each side.

- The third group made up the base of the triangle and was important for towing horse transports.

- The fourth and last group acted as a reserve in the rear, covering any weak spots.

This close and dense triangle shape helped Roman ships protect each other from attacks on every side. It also allowed them to focus their force at one point and respond quickly if attacked.

Carthage, famous for its naval skill, used classic tactics but also tried new ideas against Rome. The first move was to form a long, stretched-out line that could surround the Romans. Instead of a direct attack, Carthaginian leaders planned to pull back in the center and fall away as the Romans came forward.

Planned Carthaginian actions:

- Weaken the middle and pull Roman ships into a trap.

- Extend the wings to outflank the enemy.

- Use their fastest ships on the right side, close to the sea, and anchor the left near land.

The real strength of Carthage was in breaking up the Roman group before hitting them hard from the sides and behind. If they succeeded, they could use their skills in quick movement and ramming to destroy smaller groups instead of fighting a head-on battle.

Commanders and Leadership

During the clash at Ecomis, the Roman fleet was led by two consuls: Lucius Manus Volo and Marcus Atius Regulus. Each consul commanded his own squadron, positioned at the front of the fleet’s triangular formation. This placement allowed them to make decisions quickly and adjust tactics as the battle developed.

The Romans divided their forces into four main groups:

| Division Number | Role | Leadership |

|---|---|---|

| First | Formed the tip of the triangle, spearheading attack | Led by a consul |

| Second | Supported the tip, next in line | Led by the other consul |

| Third | Held the base, protected support vessels | Senior naval officers |

| Fourth | Guarded the rear as a reserve (“triari”) | Experienced commanders |

Consuls not only directed ship maneuvers but were also responsible for rapid, high-stakes decisions, such as launching attacks or shifting formation. Their presence at the front signaled the importance of strong, visible leadership in battle.

Carthaginian Commanders and Battlefield Strategy

Carthage placed its forces under the overall command of Hamilcar in Sicily and Hano, who previously defended Agrigentum. This pair of leaders worked in close coordination, each managing key sections of the fleet to execute complex maneuvers.

Their battle plan focused on exploiting Rome’s inexperience at sea:

- Hamilcar took charge of the main center, including the weakest part of Carthage’s formation.

- Hano commanded the swiftest ships on the right flank, ready to strike quickly at vulnerable spots.

The Carthaginians extended both wings of their fleet and intentionally weakened the center. As the Roman front attacked, Carthaginian captains withdrew, giving the illusion of retreat. This tactic was designed to lure the Romans in and then envelop them from the sides and rear.

This leadership showed careful planning and a deep understanding of both sides’ strengths and weaknesses. Delegated commands, overlapping flanks, and feigned retreats were all used to try and outmaneuver Rome’s heavy reliance on close combat and boarding tactics.

How the Battle Unfolded

Fleet Positions and Early Maneuvers

At Eomis, both navies deployed in formations shaped by their tactics and technology. The Roman fleet formed a tight triangle with overlapping defenses. The tip of this triangle was led by Roman consuls, with their divisions spreading out behind them. Horse transports and reserves made up the rear.

The Carthaginian fleet lined up broadside, but their leaders chose not to engage head-on. Instead, they stretched their wings wide to surround the Romans. The flanks pressed close to shore and extended far into the open sea, aiming to outmaneuver the dense Roman formation.

Here’s a simple breakdown:

| Side | Formation | Strengths Targeted |

|---|---|---|

| Roman | Triangle | Defensive overlap, close ranks |

| Carthaginian | Line, extended | Maneuver, flanking, ramming ability |

Carrying Out Battle Tactics

Roman leadership wanted to break the enemy’s line quickly. They saw a weakness in the Carthaginian center and attacked head-on, pushing their vanguard forward. As Romans surged, the Carthaginian center withdrew slowly, luring the Roman front deep ahead.

The Carthaginians clung to their plan. Their outer wings sped up to start enclosing the Roman ships from the sides and behind. Battleships at the flanks, and the fastest ships on the extreme right, aimed to use their edge in speed and ramming.

Both navies aimed to use their advantages—Romans ready to board, Carthaginians looking to isolate opponents and strike from better positions.

- Romans: Focus on boarding enemy ships using the corvus bridge.

- Carthaginians: Attempt to break apart the Roman formation and attack from the flanks.

Battle’s Key Moments

The turning point came after the Romans’ rapid advance. Their lead divisions moved far ahead, leaving a gap in the fleet. Noticing the Romans spread out, the Carthaginian command signaled a sudden attack.

The Carthaginian ships swung around and engaged the leading Roman ships. The compact Roman line was now broken up, making it harder for ships to support each other.

In summary:

- The Roman front was drawn out of formation.

- Carthaginian ships launched a coordinated assault from several directions.

- Fierce fighting broke out as both sides tried to use their chosen tactics under chaotic conditions.

Effects on Sea Battles and Historical Importance

The clash at Eomis set a remarkable benchmark for future sea warfare. It involved more ships and crew than many other famous battles in history. For example:

| Naval Battle | Ships Involved | Personnel Involved |

|---|---|---|

| Eomis | 680 | ~290,000 |

| Salamis | Similar size | ~200,000 |

| Lepanto | 484 | ~150,000 |

| Spanish Armada (1588) | 330 | N/A |

| Jutland (WWI) | 250 | ~100,000 |

| Leyte Gulf (WWII) | 367 | ~200,000 |

The size and planning of this confrontation showed what was possible with enough organization and resources. Later battles, like Lepanto and Leyte Gulf, did not reach the same level of ships or men as Eomis. This battle proved early on how critical control of the sea could be for any military campaign.

The events at Eomis also highlighted the importance of Sicily as a strategic crossroads. The powerful fleets competing for dominance showed later powers how vital naval forces were for securing territory and supply lines.

Review of Strategies and Battle Plans

Both Carthage and Rome brought new methods to the battle. Carthaginian naval tactics relied on speed and sharp ramming moves—a tried and true approach in sea combat. Romans, less experienced at sea, invented the corvus boarding device. This tool helped them make up for their lack of naval practice by turning fights into hand-to-hand battles, where they were stronger.

The fleets formed in careful shapes and lines, with the Romans using a triangle to overlap their defenses. Carthaginian leaders tried to trick the Romans by letting their center look weak, hoping to draw the Roman center forward and then attack from the sides and back. Roman commanders reacted quickly when they saw this weakness, charging ahead to strike.

The tactics used by both sides at Eomis became lessons for later generations. Plans that focused on formation, deception, and using unique tools like the corvus had lasting impact. Many future admirals and generals would study these choices when planning their own sea battles.