You step into a short period when Rome moved away from fear and chaos and tried steadier rule. You guide viewers through the rise of an older senator who took power after a sudden death and faced pressure from the army, the Senate, and the public. You explain how calm promises and careful choices aimed to restore trust, even as limits and risks followed him.

You then lead into the rule of a skilled soldier who gained loyalty through action and discipline. You show how firm leadership, public works, and hard wars reshaped Rome’s reach and daily life. You frame this shift as a turning point that set up the next chapter of rule.

Key Takeaways

- Power shifted toward steadier rule after a violent era.

- Careful reforms met real limits without army support.

- Strong leadership expanded borders and shaped succession.

The Era of the Five Good Emperors

How the Label Took Shape

You hear the phrase “Five Good Emperors” because it contrasts sharply with rulers like Nero and Caligula. After years of fear and sudden violence, this period marked a pause from harsh and unpredictable rule.

You see the shift begin when the Senate chose Nerva after Domitian’s death. That choice alone set a different tone, since the Senate had little say under earlier emperors.

How Their Rule Stood Apart From Earlier Emperors

You can compare this era to the reign of Domitian by looking at how power worked. Nerva promised to work with the Senate and vowed not to kill senators for political reasons.

You also notice changes in daily rule:

- Fewer political executions

- Returned confiscated land

- Tax relief for some citizens

- Public works like roads and aqueducts

You still see limits and flaws, especially when Nerva failed to control the Praetorian Guard. Even so, compared to past terror and fear, this style of leadership felt calmer and more restrained.

Rise of Emperor Nerva

Origins and Early Standing

You come from a noble Italian family, born between 30 and 35 AD in the town of Narnia. Records say little about your youth, but you grow up close to power through long family ties to Rome’s inner circle.

You later serve as an adviser and trusted companion to Emperor Nero. Under Vespasian, you earn an early consulship, which places you among Rome’s political elite.

Steps Toward the Throne

You hold another consulship under Domitian, though large gaps remain in the record of your career. Everything changes on September 18, 96 AD, when Domitian is assassinated.

Before the day ends, the Senate names you emperor. You take power as an unexpected choice: elderly, physically weak, and without a direct heir, which raises quiet suspicion about your role in the transfer of power.

Dealings with the Senate

You rule with clear respect for the Senate, which welcomes your rise after Domitian’s harsh rule. You promise to include senators in governance and vow never to execute one for political reasons.

You reverse land seizures, reduce certain taxes, and return confiscated property. These actions strengthen senatorial support, even as they strain the treasury and force you to cut spending elsewhere.

Nerva’s Reforms and Governance

Restoring Property and Funding the City

You return land taken by the last emperor and give plots to poor Roman citizens. You remove some tax burdens to ease daily life.

You also spend on roads and aqueducts across Rome. When the treasury thins, you cut costs, ban new statues of yourself, and sell items from the former ruler to raise funds.

Working with the Senate and Facing Limits

You promise the Senate a real role in rule and keep that word. Yhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A8sW4Xcwmj0&t=1sou swear that no senator will die by your order, which marks a clear break from past rule.

The Senate favors you for this approach. Still, your age, poor health, and lack of an heir weaken your position and limit your authority.

Clashes with the Praetorian Guard

You refuse to punish the men who killed the former emperor, hoping to calm tensions. The guard sees this as weakness and keeps pressing their demands.

In 97 AD, members of the guard storm the palace and take you hostage. They force your hand, leave you humiliated, and expose the danger of your passive stance.

Succession and the Rise of Trajan

Choosing a Successor

You rule after Domitian’s murder in 96 AD, chosen by the Senate in a rare move. You face deep mistrust from the Praetorian Guard, who still favor the old emperor and demand revenge.

You try to calm every group, but this restraint weakens your position. When the Guard storms the palace and takes you hostage in 97 AD, the crisis forces a clear choice. You name a respected general, Trajan, as your adopted heir to secure army support.

Key pressures shaping your decision:

- Loss of control over the Praetorian Guard

- No biological heir

- Need for military loyalty to stabilize rule

Trajan’s Early Life and Military Path

You select Trajan, born Marcus Ulpius Traianus in the mid–1st century AD, from a noble family with strong military ties. His early years remain unclear, but his rise through the army stands out.

You rely on his reputation as a capable commander. He earns the title Germanicus for leadership in Germania Superior and serves as consul in 91 AD. His standing with soldiers makes him the figure you need.

After your death in January 98 AD, Trajan does not rush to Rome. You watch him move along the Rhine and Danube frontiers first, showing where his priorities lie. When he finally arrives, he takes power with firm control and the army firmly behind him.

Rule of Emperor Trajan

Early Actions and Style of Rule

You take power after a long journey back to Rome, stopping at the Rhine and Danube fronts before claiming the throne. You present yourself as open to advice and cooperation, even though you keep real control in your own hands.

You continue public gifts and land grants, much like your predecessor, and you support building projects that benefit daily life. People soon give you the title Optimus Princeps, showing trust in your steady and fair rule.

Key traits of your early rule:

- Preference for calm governance

- No use of terror or mass punishment

- Respect for tradition and order

Dealings with Senators and Elite Families

You face early doubt from the Senate, but you avoid conflict and ease their concerns through respect and restraint. You signal that you want harmony, and you avoid choices that would openly defy senatorial opinion.

You also show clear favor toward educated Greek nobles, whom you see as useful allies and capable advisers. This choice causes quiet tension, since many Greek elites dislike Roman control, but it does not weaken your standing in Rome.

| Group | Your Approach |

|---|---|

| Senate | Cooperation without surrendering power |

| Roman nobility | Fair treatment and stability |

| Greek elites | Select favor based on skill and loyalty |

Trajan’s Major Wars and Advances

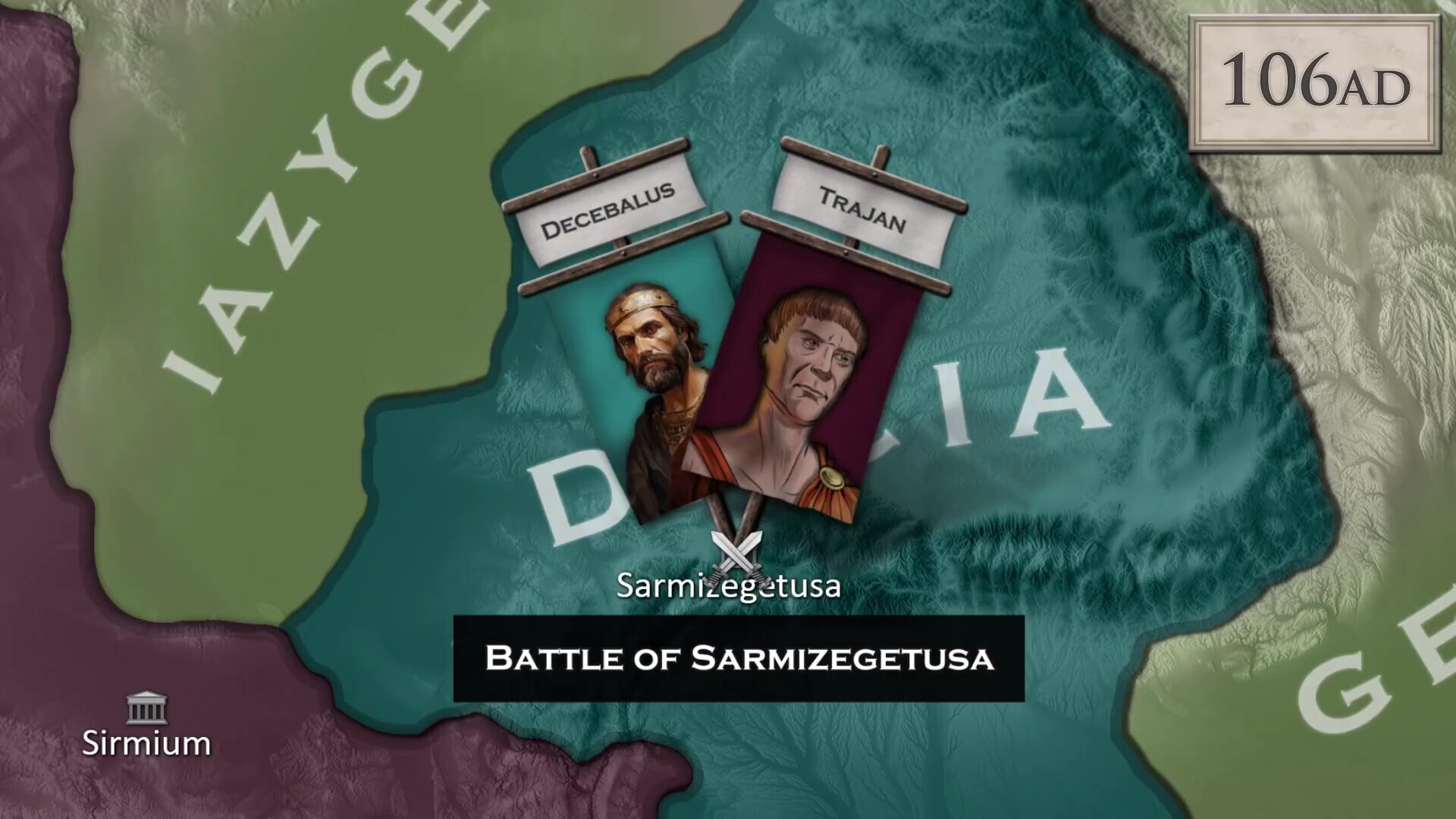

Fighting Dacia and Decebalus

You face Dacia as a long-time threat along the Danube. In 101 AD, you lead a renewed invasion and win a major victory that forces a harsh peace on King Decebalus.

By 105 AD, Decebalus breaks the agreement and attacks Roman lands again. You respond fast, push deep into Dacia, and surround his capital. Decebalus takes his own life, and you bring the kingdom under Roman control.

Key outcomes

- Dacia becomes Roman territory

- Roman forces secure the Danube border

- Enemy resistance collapses after sustained pressure

Moving East into Armenia and Mesopotamia

You turn east when Parthia places its own ruler on the Armenian throne. You see this as an open challenge and march into Armenia without delay.

You remove the king and claim the land for Rome. You then split your army and advance through Mesopotamia, taking city after city until even the Parthian capital falls into your hands.

| Region | Action Taken | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Armenia | King removed | Roman control imposed |

| Mesopotamia | Full invasion | Major cities captured |

Dealing with Parthian Power

You reject Parthian attempts to calm the conflict through compromise. Even after they replace their chosen ruler, you refuse to step back.

You press the war further and expand Roman borders to their greatest reach. Your campaign leaves Parthia weakened and Rome dominant across the east.

Lasting Impact of Nerva and Trajan

You see Nerva set a new tone by easing fear in Roman politics. You treat the Senate with respect, return seized land, cut harsh laws, and protect senators from execution tied to your rule.

You also face limits. By avoiding firm action with the Praetorian Guard, you appear weak, and they humiliate you by taking you hostage. You respond by choosing a strong military heir to steady the state.

Key marks of Nerva’s rule

- Restores property and offers land to poor citizens

- Reduces waste and refills the treasury

- Promises shared rule with the Senate

- Adopts Trajan to secure army support

You carry that stability forward as Trajan and expand Rome’s reach. You keep peace at home, avoid tyranny, and gain trust by ruling without terror. You accept the title Optimus Princeps as your reputation grows.

You also reshape Rome through war and building. You defeat Dacia after hard campaigns, add its lands to the empire, and later push east after conflict over Armenia. Your victories carry Rome to its widest borders.

| Emperor | Political Approach | Military Role | Lasting Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nerva | Works with the Senate | Relies on adoption | Smooths succession |

| Trajan | Rules without fear | Leads major campaigns | Expands the empire |

You leave Rome powerful and ordered, with public works, gifts to citizens, and_ borders secured by force when you judge it necessary.

Transition to Hadrian

You see the change begin after Trajan’s final campaign. In the summer of 117 AD, he died while away from Rome, after falling ill during his return journey.

His body went back to the capital, and power shifted quickly. You now have a new ruler, a relative of Trajan, raised to command the empire after his death.

This handover marked a clear break from constant expansion. You move forward under a leader tied by blood to Trajan, but facing a very different set of choices as emperor.