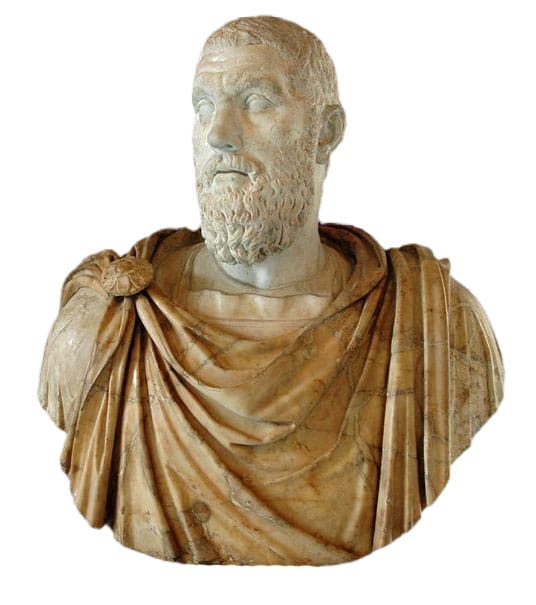

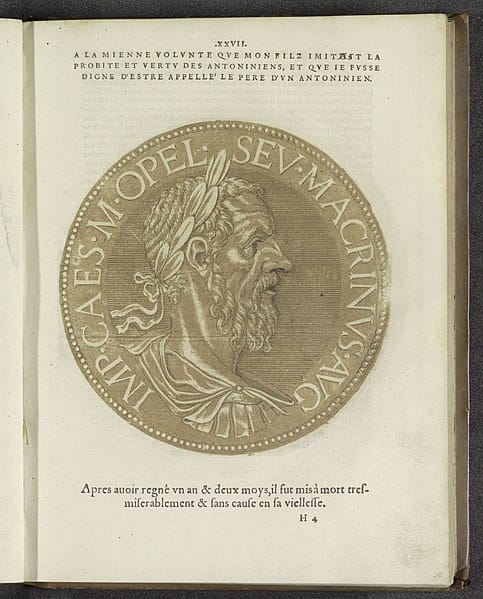

Life: AD 164 – 218

- Name: Marcus Oppellius Macrinus

- Born AD 164 at Caesarea in Mauretania.

- Consul AD 218.

- Became emperor on 11 April AD 217.

- Wife: Nonia Celsa (one son; Marcus Opellius Diadumenianus).

- Died at Antioch June-July AD 218.

Early Life

Marcus Opellius Macrinus was born in AD 164 in Caesarea, a harbor town in Mauretania. There are two stories surrounding his origins. One tells of him being from a poor family and, as a young man, having made his living as a hunter, a courier – even a gladiator at times. The other describes him as a son of an equestrian family who studied law.

The latter is perhaps more likely. When he moved to Rome, he gained a reputation as a lawyer. Such was the reputation he achieved that he became the legal adviser to Plautianus, the praetorian prefect of Septimius Severus, who died in AD 205. Afterward, he worked as director of traffic on the Via Flamina and then became the financial administrator of Severus’ private estates.

Becoming a Praetorian Prefect

In AD 212 Caracalla made him praetorian prefect. In AD 216, Macrinus accompanied his emperor on a campaign against the Parthians, and in AD 217, while still campaigning, he received consular rank (consular status without office: ornamenta consularia).

Macrinus is described as a stern character. As a lawyer, though not a great expert in law, he was conscientious and thorough. As praetorian prefect, he is said to have had good judgment whenever he sought to act. But in private, he is also reported to have been impossibly strict, frequently flogging his servants for the slightest of mistakes.

In the spring of AD 217, Macrinus intercepted a letter, either from Flavius Maternianus (commander of Rome in Caracalla’s absence) or from an astrologer of Caracalla’s, denouncing him as a possible traitor. If only to save his own life from the vengeance of the bloodthirsty emperor, Macrinus needed to act. He quickly found a possible assassin in Julius Martialis.

Asination of Caracalla

There are two differing reasons given for Martiali’s anger at Caracalla. One by the historian Cassius Dio points out that the emperor had refused to promote him to the centurion. The other version, by the historian Herodian, tells us that Caracalla had had Martialis’ brother executed on a trumped-up charge only a few days earlier. I would assume that the latter of the two versions sounds more credible to most. In any case, on 8 April AD 217, Martialis assassinated Caracalla.

Though as Martialis tried to get away, he was himself killed by Caracalla’s mounted bodyguards. This meant there was no witness to link Macrinus with the murder. And so Macrinus feigned ignorance of the plot and pretended grief at his emperor’s death. Caracalla, though, had died without a son. There was no obvious heir.

Becoming an Emperor

Oclatinius Adventus, Macrinus’ colleague as praetorian prefect, was offered the throne. But he decided that he was too old to hold such office. And so, only three days after Caracalla’s assassination, he was offered the throne. He was hailed emperor by the soldiers on 11 April AD 217.

Macrinus, though, knew very well that his being emperor depended entirely on the goodwill of the army as he at first had no support at all in the senate. – He was the first emperor not to be a senator! So, playing on the army’s liking of Caracalla, he deified the very emperor he’d assassinated.

The senate, faced with no alternative but to acknowledge him as emperor, though, was, in fact, quite glad to do so, as the senators were simply relieved to see the end of the hated Caracalla. Macrinus won further senatorial sympathies by reversing some of Caracalla’s taxes and announcing an amnesty for political exiles.

Death of Julia Domna

Meanwhile, Macrinus should win an enemy who should seal his fate. Julia Domna, the wife of Septimius Severus and mother of Caracalla, quickly fell out with the new emperor. Most likely, she came to know what part Macrinus had played in her son’s death. The emperor ordered her to leave Antioch, but Julia Domna, seriously ill by then, instead chose to starve herself to death.

War Against Parthia

Julia Domna, however, had a sister, Julia Maesa, who laid the blame for her death with Macrinus. And it was her hatred that should come to haunt him very soon. Meanwhile, he was gradually losing the support of the army as he tried to disentangle Rome from the war with Parthia, which Caracalla had begun. He handed Armenia to a client king, Tiridates II, whose father Caracalla had imprisoned.

Meanwhile, the Parthian king Artabatus V had gathered a powerful force and, in late AD 217, invaded Mesopotamia. Macrinus met his force at Nisibis. The battle ended largely undecided, though possibly slightly in favor of the Parthians. In this time of military setbacks, he then committed the unforgivable mistake of reducing military pay.

Problem Called Elagabalus

His position weakened by an increasingly hostile military, Macrinus next had to face a revolt by Julia Maesa. Her fourteen-year-old grandson, Elagabalus, was hailed emperor by the Legio III ‘Gallica’ at Raphanaea in Phoenicia on 16 May AD 218. The rumor, put out by Elagabalus’ supporters, that he was, in fact, the son of Caracalla spread like wildfire. Mass defections quickly began to enlarge the challenger’s army.

As both Macrinus and his young challenger were in the East, there was no effect the powerful legions based at the Rhine and Danube could have. Macrinus at first sought to quickly crush the rebellion by sending his praetorian prefect Ulpius Julianus with a strong cavalry force against them. But the cavalrymen simply killed their commander and joined the ranks of Elagabalus’ army.

Augustus Diadumenianus

In an attempt to create the impression of stability, Macrinus now pronounced his nine-year-old son Diadumenianus joint Augustus. Macrinus used this as a means to cancel the previous pay reductions and distribute a large bonus to the soldiers in the hope that he may win back their favor. But it was all in vain as soon after, an entire legion deserted to the other side. So dire did the desertions and mutinies in his camp become that Macrinus was forced to retire to Antioch.

The Battle of Antioch

The governors of Phoenicia and Egypt remained loyal to him, but Macrinus’s cause was lost, as they could not provide him with any significant reinforcements. A considerable force under the command of the rival emperor’s general, Gannys, finally marched against him. In a battle outside Antioch on 8 June AD 218, Macrinus was decisively defeated and abandoned by most of his troops.

Disguised as a member of the military police, having shaved his beard and hair, Macrinus fled and tried to make his way back to Rome. But at Chalcedon on the Bosporus, a centurion recognized him, and he was arrested. Macrinus was taken back to Antioch, and there he was put to death. He was 53. His son Diadumenianus was killed soon after.

People Also Ask:

What was Macrinus known for?

Macrinus was a Roman emperor in 217 and 218, the first man to rule the empire without having achieved senatorial status. Died: June 218, in Bithynia [now in Turkey].

How long did Macrinus rule?

Marcus Opellius Macrinus (/məˈkraɪnəs/, mə-CRY-əs; c. 165 – June 218) was Roman emperor from April 217 to June 218, reigning jointly with his young son Diadumenianus.

Which emperor assassinated his brother?

A not-so-festive case of fratricide: on 19 December 221 CE, Caracalla killed his brother Geta in order to gain full command of the Roman Empire. The sons of Septimius Severus, the brothers had co-ruled with their father since 209.

Was Macrinus a Moor?

Macrinus was a Moor by birth, from Caesarea, and the son of most obscure parents, so that he was very appropriately likened to the ass that was led up to the palace by the spirit; in particular, one of his ears had been bored in accordance with the custom followed by most of the Moors.

How did Macrinus rule?

Macrinus was Roman emperor from April 217 to June 218, reigning jointly with his young son Diadumenianus. As a member of the equestrian class, he became the first emperor who did not hail from the senatorial class and also the first emperor who never visited Rome during his reign.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.