Period: AD 337 – 476

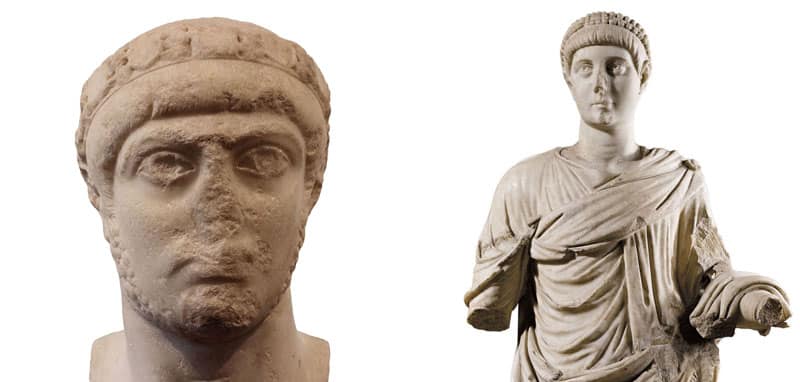

Flavius Claudius Constantinus – “Constantine II”

Reign: AD 337 – 340

Flavius Julius Constantius – “Constantius II”

Reign: AD 337 – 361

Flavius Julius Constans – “Constans”

Reign: AD 337 – 350

At Constantine’s death at Nicomedia in AD 337, three sons and two of his nephews were destined by the late emperor to succeed him. Though two of those sons were absent from Nicomedia. With the consent of the third, Constantius, the other members of the imperial family, except two young cousins were slaughtered by the soldiery.

The empire was thereafter by agreement parted between the three sons. Constantine taking the west, Constans the centre and Constantius the east. The eldest of the three new emperors was twenty one; their two cousins, Gallus and Julian, the nephews of the great Constantine, were in AD 337 aged twelve and six respectively.

From the outset Constantius was thoroughly occupied in coping with the activities of the Persian King Sapor II. Was Constantius engrossed in the quarrel with the Persian Sapor II over Armenia, then the real seat of the struggle soon was in Mesopotamia, where the war raged for some years without any decisive result. Both sides called into action Arab horsemen, who raided and wrought havoc far and wide; nine pitched battles were fought, in which, by admission of roman historians, the advantage generally lay with the Persians. Constantius himself was twice present; but it is safe to assume that his officers, not he, were responsible for the military direction. Meanwhile Constantius’ brothers, Constantine and Constans, were quarreling and then actually fighting over the possession of Illyria. The elder, Constantine, was slain in an ambush near Aquileia (AD 340), and the younger, Constans, was recognized throughout the western dominion. But Constans now conducted himself as an irresponsible tyrant. Loyalties soon waned and when Magnentius was acclaimed by the legions while the emperor was away hunting, Constans could only flee for his life, only to be overtaken and slain on the Spanish coast.

Flavius Magnus Magnentius – “Magnentius”

Reign: AD 350 – 353

If Magnentius in AD 350 was recognized immediately in the prefectures of Gaul and Italy, then in Illyria another general Vetranio was set up as emperor.

In the east Constantius still locked horns with Sapor II. Alas the King of Persia was called to see to other problems in the east of Persia, as news reached Constantius of the death of Constans and two new emperors being in place in the west. Both Sapor II and Constantius left Mesopotamia, leaving behind a devastated no-man’s-land. The two new emperors meanwhile made haste to come to terms and to proffer their equal amity to the surviving son of Constantine in the east. But for Constantius reconciliation with his brother’s murderer Magnentius was impossible. Far more won over Vetranio as his ally and took to war against Magnentius, defeating him at the grueling Battle of Mursa in Pannonia where 50’000 of the best troops of the imperial armies were left dead. Though Magnentius himself was not dead, he sought to continue the war, but his troops gradually deserted him. By the time those who remained were ready to deliver him to the enemy, if only to spare themselves, he chose suicide. Had Constantius left his cousin Gallus in charge of ruling the east, it was only to learn that Gallus was an irresponsible tyrant and was already planning on treason. Gallus was summoned to Pannonia where he met with an executioner’s sword in AD 354. Except for Constantius himself, the only surviving male descendant of Constantine the Great was Julian, the younger brother of Gallus. Julian lived in Athens devoting himself to literary and philosophical studies. He had no practical experience of rule and sought none. Yet against his will Julian was raised by Constantius to Caesar with the souvereignty over transalpine Europe. The fact that the empire was too large to be managed without viceroys was once more proving itself; especially since the Persian King Sapor II, having dealt with his problems to the east of Persia, was now back at the Roman borders to renew his ambitions.

The barbarians moreover were again swarming over the upper Danube.

Constantius occupied himself with the barbarian problem while his lieutenants dealt with Sapor in Mesopotamia.

Though the Persian army was vastly superior in numbers, it eventually exhausted itself in several vain attempts to conquer the stubbornly defended fortress city of Amidia. Alas their numbers depleted and, though the war went on, the great threat to the eastern empire was averted. Meanwhile the reluctant Julian was proving himself a valiant man of action in Gaul and on the Gallic frontier. A strong man was certainly needed in Gaul; for in the civil war Magnentius had called to his aid hosts of Franks and Alemanni, who promptly assumed the role not of auxiliaries but of conquerors.

Despite his inexperience and his academic predilections, Julian proved himself equal to the emergency, winning battles against heavy odds with distinguished personal valour, and restoring law and order in the devastated districts.

Until the reputation he was winning aroused the jealousy of Constantius, whose own credit was being not at all enhanced by his operations in the east, neither as soldier nor as ruler.

Jealousy rapidly developed into suspicion and probably into secret designs against the life of the younger man.

Constantius ordered an immediate dispatch of the best of the legions of Julian to the Mesopotamian front. The legions responded by calling upon Julian to save the empire by assuming the purple of Augustus.

For some time Julian held out loyally, but the soldiery would take no denial till he yielded, at last convinced that loyalty to the empire was above loyalty to the emperor.

Flavius Magnus Magnentius – “Julian the Apostate”

Reign: AD 360 – 363

Though Julian professed to demand only his own recognition as Western Augustus, Constantius naturally refused to look on his as anything but a rebel. When this was made clear to Julian and his legions there remained no alternative but civil war. And suddenly Julian with no more than three thousand men vanished into the forests and mountains of south Germany to reappear on the lower Danube. Constantius, returning from his inglorious campaign in the east, was taken ill in Cilicia, and died AD 361.

There was no civil war.

Julian the Apostate crossed over to Asia, his title of Augustus undisputed, and never returned to Europe.

Julian reigned for no more than two years. He bears the name ‘Apostate’ because he renounced the Christianity of his earlier years and proclaimed himself the champion of the ancient gods.

Though, if Julian did refute Christianity, his method of suppressing the religion he discarded was not that of persecution in the ordinary sense. He went no further than to exclude Christian teaching and teachers from the schools.

For the rest of his reign Julian remained occupied with the Persian war. A victorious campaign in which he penetrated beyond the Tigris ended in disaster. The army advancing under the direction of rashly trusted guides, was lead into a trap. It was almost overwhelmed by the myriads of foes by which it found itself surrounded. Yet valour and skill broke every onslaught. But in the pursuit which followed the last repulse, Julian was wounded by a javelin and was carried back to camp, only to die. (AD 363)

Flavius Jovianus – “Jovian”

Reign: AD 363 – 364

There was no surviving male descendant of the imperial house and Julian had named no successor. The army chose an old soldier, Jovian, who lived long enough to patch up a peace with Persia and withdraw. But six months after his accession Jovian died.

Flavius Valentinianus – “Valentinian”

Reign: AD 364 – 375

Flavius Julius Valens – “Valens”

Reign: AD 364 – 378

Again the choice lay with the soldiery. In AD 364 a barbarian of Pannonian stock and common descent but proved capability was elected to be Rome’s new master, Valentinian.

By his first act the new emperor recognized the practical necessity for partition. No one man could successfully hold in his own hands for long the responsibility for both east and west. Valentinian chose for himself his native west, and made his brother Valens Augustus of the east. This time the division was permanent, though the empire still remained nominally one.

For twelve years Valentinian ruled the west with vigour and, apart from his savage mercilessness toward any opposition, with justice and moderation.

Valentinian was rigid in his insistence on equal treatment for all religions, he held the Gallic frontiers with a strong hand against swarming Franks and Alemanni who he defeated in successful campaigns beyond the Rhine.

It was on a campaign against the Quadi on the upper Danube that one of those outburst of ungovernable rage which marred his character wrought his own undoing inducing an apoplexy that killed him.

Flavius Gratianus – “Gratian”

Reign: AD 367 – 383

Flavius Valentinianus – “Valentinian II”

Reign: AD 375 – 392

On Valentinian’s death, his elder son Gratian was at once recognized as his successor. Gratian’s mother had been discarded by Valentinian in favour of a wife who bore him another son, Valentinian II, whom Gratian immediately named as co-emperor.

Had since Constantine Christian emperors always been able to accept several religions in being within their empire, then Gratian was the first to be unable to tolerate this.

Had over time privileges been bestowed upon the church then the privileges for the state religion had still remained. The latter were now being withdrawn. In consequence none-Christians were beginning to grow restive, whilst the Christian church was becoming increasingly intolerant of others.

Meanwhile in the east still ruled Valens. His appointment as emperor of the east proved to be the gravest error of judgement Valentinian had ever made. The worst faults of Valens were feebleness and indecision, not brutality. And to these weaknesses it was due that King Sapor II in his old age finally was able to establish complete if detested mastery over Armenia.

However, the great disaster in the reign of Valens did not befall the empire till after the death of Valentinian.

About the middle of the century the widespread Gothic confederation had been extending and consolidating its territories between the Baltic in the north and the Danube and Black Sea in the south, under the leadership of Hermanaric the Amal, whom all tribes recognized as King. But during the same period a new and formidable foe was pouring from Asiatic Scythia into European Scythia, the flood of the terrible Huns.

Now it rolled down on the Goths. Officially at the least the Goths were now friends of Rome. Reeling under the shock, the Visigoths sought the aid of Valens, who granted them wide lands for settlement on the southern side of the Danube barrier. Their vast swarms, only in part disarmed, were ferried across the river by hundreds of thousands, in numbers which had been utterly underestimated. The cramped starvation conditions to which they were subjected were wholly intolerable. Hence arose on the hither side of the Danube defences a new enemy.

Valens had in effect created his own disaster. War now raged in the Balkans, a war so critical that Valens called upon Gratian to come to his aid.

But Gratian had hardly less serious embarrassment of his own, for the Alemanni were upon him. It was not until he had won a decisive crushing victory over them that he could report himself as on the march to effect a junction with the army in the east.

But Valens would not wait. In the neighbourhood of Adrianople he flung himself upon the Goths and in the battle that followed his army was annihilated, he himself perished, and the triumph of the Goths was complete (9 August AD 378).

The battle of Adrianoble stopped the advance of Gratian. Tremendous though the disaster had been, Adrianople and the greater capital on the Bosporus could defy the onslaughts of the Goths, who were no experts in siege warfare. But for Gratian to have marched on the Goths would have meant to risk disaster in both east and west. the Alemanni had been disposed of only for the moment.

Gratian made haste to pronounce a new emperor in the east to take in hand the Gothic problem.

His choice fell upon Theodosius, the son of a great captain and servant of the state on whom in Gratian’s first year the intrigues of traitors had brought the undeserved penalty of treason. The son, who had already had time to prove his capacity, had been suffered to retire into private life; and was now raised to the purple at the age of thirty-three.

Flavius Theodosius – “Theodosius I”

Reign: AD 379 – 395

Magnus Maximus – “Magnus Maximus”

Reign: AD 383 – 388

Theodosius took up his hard task with admirable skill and prudence, but no lack of courage. Hermanaric had fallen before the Gothic war began. The able successor who had led the united Goths to victory died, and with his death their unity departed. Theodosius made no ambitious attempt to retrieve the position by staking the fate of the empire on a pitched battle. He risked no great engagements; but while he struck minor blows against their divided forces he encouraged their internal divisions. His diplomacy attached some of their leaders to the empire, for which they had an almost superstitious reverence. In little more than four years a comparatively enduring if precarious peace was established.

Gratian meanwhile was losing the high reputation he had won. Of his courage and his private virtues there could be no question, but the appearance of high capacity may have been due to his early submission to wise direction. Further he made the mistake of abandoning much of the cares of state for amusements, which brought him into contempt with the soldiery.

Theodosius had hardly set the seal on his own reputation in AD 382 by his much applauded treaty with the Goths, when the army in Britain, as in the days of Carausius, renounced its allegiance to Gratian and proclaimed an emperor of its own choice. The Spaniard Maximus reluctantly accepted the dangerous honour.

In AD 383 Maximus crossed the Channel with a great force which depleted the garrison of the island, and marched upon Lutetia (Paris) where Gratian was residing. The soldiery in Gaul refused to move. Gratian fled, but was overtaken at Lyons, where he was treacherously assassinated, though without any connivance of the British emperor.

The successful usurper had nothing to fear from the boy Valentinian II – or rather from his mother Justina – reigning at Milan. But he hastened to send an embassy to Theodosius, repudiating and condemning the murder which had been so hastily committed in his name, but justifying his own assumption of the purple and inviting the friendly alliance of the eastern emperor. Theodosius may well have felt that the pacification he had just effected was too precarious to warrant him in plunging the empire into a civil war, whose result would be doubtful, though justice and honour demanded the punishment of Gratian’s murderer. He contented himself with recognizing the title of Maximus in the Gauls and Britain as a third Augustus, provided that the souvereignty of Valentinian II in Italy, Africa and western Ilyria were unquestioned. And to those terms Maximus agreed.

But the excessive ambition of Maximus brought about his own downfall. Justina was unpopular as Italy was fanatically Christian orthodox, whereas she was an Arian heretic. Maximus seized this as an excuse to invade Italy. Justina fled to Theodosius with Valentinian II and her daughter. The emperor fell in love with the daughter and married her.

Theodosius’ cautious policy was blown to the winds, Maximus was promptly wiped out and Valentinian II was restored to the empire of the west, where on his mother’s death, he fell completely under the influence of the orthodox part (AD 388).

His reign was brief although he had barely emerged from boyhood. The supreme command in Gaul was conferred on the pagan Frank, Arbogast, an able captain who had stood loyal to Gratian and had taken service with Theodosius instead of Maximus. The Frank now gave way to aspirations of his own. After a quarrel with Arbogast, Valentinian II committed suicide or was murdered, and Arbogast set up in hi place his own puppet, Eugenius in AD 392.

In AD 394 Theodosius disposed of the usurper, and divided the succession in east and west between his own sons Arcadius (382-408) and Honorius (AD 384-423). The latter at once became western emperor, and on the death of Theodosius in AD 395 Arcadius succeeded him at Constantinople.

Flavius Honorius – “Honorius”

Reign: AD 395 – 423

Flavius Claudius Constantinus – “Constantine III”

Reign: AD 407 – 411

Flavius Constantius – “Constantius III”

Reign: AD 421

The young heirs of the powerful Theodosius were feeble and incompetent.

From the death of Theodosius to the disappearance of the western empire, mighty figures stalked across the stage, but they were not of Roman or Byzantine emperors but of barbarians: Vandal, Visigoth, Ostrogoth, Frank, or – most terrible of all – Hun.

Theodosius had named as the guardian of his sons and chief of his armies of the west a soldier of proven ability and worth, the Vandal Stilicho, who discharged his office with more loyalty than Arbogast the Frank. Virtualy the rule of the west was in his hands. While he was engaged in crushing the dangerous independence of a Moorish prince and tyrant, Gildo, in Africa, the misrule of prefect Rufinus at Constantinople brought on a great rebellion of the Visigoths – that branch of the Gothic race which had settled in Moesia and Illlyria, the Ostrogoths remaining beyond the Danube – led by Alaric the Balt.

The Goths overran Greece practically unchecked and wrought much destruction, till the appearance of Stilicho, his work in Africa accomplished, stayed their conquering career. Alaric was in danger of being enveloped, but escaped with great skill, and in fact frightened the court of Constantinople into buying him off by appointing him to the command in Illyria as an imperial officer.

The Goth accepted the position, but as a stepping stone. Italy was the objective on which he had fixed his ambitions. The were miscellaneous and for the most part barbarian troops now at his disposal were ready to follow him. And in AD 403 Honorius and Italy were terrified by an apparently wholly unexpected invasion. The genius of Stilicho, who with amazing energy gathered together troops from every possible quarter, saved the situation. in the duel between the two great captains Alaric met with a heavy defeat at Pollentia, and the caution of the Gothic chiefs compelled him for the time to abandon the contest.

Though the withdrawal of Alaric only left the way open for a fresh flood of mixed barbarians to pour into Italy in AD 406, under their chief Ragadaisus. They swept over the plain of the Po, over the Apennines into Tuscany on their way to wipe out Rome. But while they delayed to besiege Florence Stilicho again gathered troops in the north, spread them round the besieging hosts, cut off the supplies of the barbarians and reduced them by sheer starvation. Radagaisus with a third of his forces was compelled to capitulate. He himself was slain. The rest of the horde, Vandals, Sueves, Burgundians, Ostrogoths, Huns and Alans were deliberately allowed to retreat unmolested across the Alps, and their various bands were soon spoiling and looting in Gaul on their way to Spain, reinforced by their respective homelands (AD 406).

Thus it was only Italy that was spared of the invaders, who in AD 407 were harrying Gaul.

And the harrying of Gaul was the excuse for the army of Britain to proclaim its own Augustus. Constantine III, probably a native Briton, was raised to the purple and set out to Gaul to save it from the Germans and add it to his own empire, taking with him a substantial part of the British garrison. The Vandals, Sueves and Alans, however, did not seek to remain permanently in Gaul to dispute possession with Constantine, but took their devastating way through the south to Spain, where they established themselves.

On the middle Rhine the Burgundians appear to have remained in effective possession. Constantine III pushed into Spain, established his dominion in Aragon, and succeeded in extorting from Honorius his own recognition as a third Augustus.

Constantine’s movement to Gaul in AD 407 is commonly referred to as the Roman evacuation of Britain.

Meanwhile Stilicho’s ambitions evidently centred on the relations between the eastern and the western empires, in both of which he sought to be the power behind the throne (as he already was in the west).

The key to this position was the possession of the whole of Illyria, and he meant Alaric to be his agent.

The eastern court had no inclination to be dominated by him, and the relations between Constantinople and Ravenna (Where for greater security Honorius had fixed his residence) were strained. Stilicho could not afford to wholly neglect the rebellion of Constantine III, but he left him to Alaric, with whom he had made his own bargain, and again Alaric only took as much action as he considered sufficient.

Early in AD 408 Arcadius, leaving the throne to the six year old Theodosius II. Almost everyone believed that Stilicho, who had married the feeble Honorius to his own daughter, meant to make himself emperor. His enemies formed a plot and gained ascendancy over the mind of Honorius. At the height of his apparent power, Stilicho was suddenly arrested, condemned without trial as a brigand and an ‘enemy of the state’ and executed. But no evidence of any treasonable designs on his part was ever forthcoming. Among those most active in his downfall was Heraclian, who was rewarded by being made Count of Africa.

Stilicho’s fall opened the way on one hand to friendly relations with Constantinople, and on the other to the ambitions of Alaric. It was the expression of the simmering hostility of Italy towards men of barbarian blood, in fact the massacre of many of the foreigners in the country, which gave the Gothic king more than adequate excuse for swooping on Italy before the year was out.

Alaric marched straight on Rome, ignoring Honorius in Ravenna. The city was rapidly reduced to starvation, and plague broke out. Alaric demanded all the treasure within it and all the barbarian slaves.

For a brief period Alaric and Honorius existed alongside each other in Italy. But in the next year the emperor’s evasions irritated the Goth into setting up the prefect Attalus as puppet emperor.Honorius, however, was made safe in Ravenna by the arrival of troops from the east. Attalus was declined to be altogether a puppet and was subsequently deposed. Further negotiations with Honorius broke down. Alaric lost patience and on August 24, AD 410 he let loose his Goths and other followers on Rome, which was sacked for three days.

Though Alaric did not proclaim himself emperor. He ravaged southward, and was planning an invasion of Africa, the granary of Italy, when at the end of the year he died.

He was succeeded by his brother-in-law, Athaulf, who abandoned the designs on Africa.

In AD 412 the Visigoths crossed the Alps into Gaul.

While Athaulf was still lingering in Italy, the empire of Constantine III was collapsing. It extended from Britain to Aragon. It broke down, partly owing to the revolt of one of his officers in Spain, Gerontius, and partly because in AD 411 the place once held by Stilicho was to some extent filled by another able soldier, Constantius. Gerontius was besieging Constantine III at Arles, when Constantius intervened on the hypothesis that both were rebels.

Gerontius retreated to Spain, where he was murdered, Constantius captured Arles, and with in Constantine III, who was executed. No sooner had Constantius returned to Italy, which Athaulf was evacuating, then a new emperor, Jovinus, was proclaimed in Gaul. Yet another complication arose when in early AD 413 Heraclian, Count of Africa, proclaimed himself emperor, too. Worse still, Heraclian, having already amassed a great fleet, sailed for Italy.

Though Heraclian’s rebellion proved an utter fiasco. He was captured and executed in midsummer. But meanwhile it had not been possible for Constantius and Honorius to take direct action in Gaul. Instead they had had to bargain with Athaulf, who then crushed Jovinus.

Now the princess Galla Placidia enters the stage. Being the sister of Honorius she was captured and carried off for bargaining purposes by Alaric during his sack of Rome. However, the princess had in Constantius a devoted admirer, who wanted her back. Naturally emperor Honorius also understood a stain on his honour that his sister should be a hostage of the barbarians.

It was part of the bargain with Athaulf that should be returned. But the Roman part of the bargain, the supply of corn to Athaulf’s troops, had been foiled by the rebellion of Heraclian. Consequently Athaulf, instead of returning the princess, married her himself in AD 414, apparently with her own willing consent, – but without that of her brother.

The marriage failed to draw Athaulf any closer to the imperial court, and Athaulf set out with his Goths and his bride to conquer Spain. There he was murdered in AD 415, and his successor Wallia struck a bargain with Rome, to make war with the other barbarians in Spain. Placidia was at last sent back to Ravenna, where she reluctantly accepted the hand of Constantius.

The Vandals, Alans, and Sueves in Spain hastened to seek peace with the empire, which they obtained; Wallia and his Visigoths were settled in Aquitania instead as ‘federates’. This meant they occupied most of the soil upon condition of military service to the empire, under their king. A similar settlement was made with the Burgundians on the Rhine. In AD 417 Wallia was succeeded by Theodoric I, probably a grandson of Alaric.

The position in Britain by this time is by no means clear. Constantine III had not left the island denuded of troops but only depleted. The Roman magistrates and the Roman government did not disappear, but hey had to make the best they could of the situation, utilizing their own resources. And the situation became progressively more difficult was the raids of the unsubdued Picts and Scots on the north, Irish Celts on the west coast and Saxon rovers on the east and south coasts increased in intensity and frequency. But many years were still to pass before the raiders established a permanent footing. In AD 421 Constantius was associated with Honorius as western emperor, but died after a few months. Princess Placidia quarrelled with her brother, who had developed an embarrassing affection for her, and retreated with her small children to Constantinople. Honorius, after a reign of twenty-five years, during which nothing whatever is recorded to his credit, died at the age of forty in AD 423.

Johannes – “John”

Reign: AD 423 – 425

The obvious successor to Honorius was Placidia’s child Valentian III, but a usurper named John, a rival of no particular merit, had to be suppressed before Placidia could effectively take up the regency in AD 425.

Flavius Placidus Valentinianus – “Valentinian III”

Reign: AD 425 – 455

The leading figure in the west, however, for nearly thirty years to come was Aetius (AD395-454), a native of Moesia, but of Italian descent. He possessed Gothic connections, his wife being of noble Gothic house, and Hun connections because he had passed long time as a hostage among the Huns.

When John the usurper was overthrown, Aetius had been engaged in bringing a Hun force to his aid. But on John’s death, Aetius made his peace with a reluctant Placidia, and was entrusted with the rule of Gaul, where he checked the aggressive expansion of the Burgundian Gunther in the east and the Goth Theodoric in the west and south, as well as the Salian Franks on the Scheldt.

But the most notable movement during Placidia’s regency was that of the Vandal-Alan group which had taken possession of southern Spain. In AD 428 Boniface the Count of Africa, had broken with the imperial government, and invited the help of the Vandals in his own ambitious projects. Africa offered a more promising field than Spain. The Vandals, led by their crafty and able King Geiseric, crossed to Africa and proceeded to ravage Mauretania in a merciless fashion.

This was not what Boniface had intended. He returned to his allegiance to Rome, but when he fought the Vandals he was so heavily defeated that he threw up the contest and retired to Italy, where his rivalry with Aetius brought about an armed conflict in which he was killed (AD 432), while the entire province of Africa was at the mercy of Geiseric. The position in Gaul was too critical to permit a reconquest of Africa. But Geiseric was quite ready to make peace in AD 435, on terms which left him practically master of Mauretania and part of Numidia.

In his conflict with Boniface, Aetius was in actual rebellion. But his rival’s fall restored his ascendancy, which became a virtual supremacy when Placidia had to surrender the regency on the marriage of Valentinian III, at eighteen to his cousin Licina Eudoxia at Constantinople in AD 437. The treaty had no sooner been made with the Vandals, then Aetis found himself forced to curb first the Burgundians and then the Visigoths. The former he broke by calling in aid from the Huns, with whose King Rugila he had always been on the most friendly terms. The Visigoths, who aimed at establishing themselves at the Mediterranean coast, were pushed back into Aquitania. But, stretched as he was, Aetius could not spare the forces to check the continued aggression of the Vandals in Africa.

So the Vandal Geiseric, inspite of the treaty of AD 435, extended his African dominion will he won Carthage. Then, satisfied of the weakness of Italy, he collected a fleet and attacked Sicily.

The menace brought the eastern empire to the aid of the west. The arrival of the eastern fleet, saw Geiseric willing to peacefully withdraw from Sicily, returning to Carthage in AD 442.

Had the Hun King Rugila died in AD 434 then his two nephews jointly inherited his powers. On of those sons, Attila, in AD 441 had attacked the eastern empire, overrunning the Balkans and devastating all he came across. Constantinople itself was not attempted, as it was deemed impregnable. In AD 443 Theodosius II came to terms, doubling his annual subsidy to Attila and agreeing to a no-man’s-land between the two empires. The conflict erupted again in AD 447, only to be halted in AD 449 with unchanged conditions. In AD 450 Theodosius II died, succeeded by the able Marcian.

But this was no longer of interest to Attila who now had his eyes set on the west.

A curious episode had perhaps determined Attila’s course. The court at Ravenna proposed to marry Valentinian III’s sister Honoria to a safe and distinguished but elderly husband. She objected and sent secretly to the mighty Hun, inviting him to rescue her.

Attila accepted the message as a betrothal and claimed his bride and half her brother’s empire as a dowry (AD 450). Valentinian III raged and rejected the demand. Meanwhile Attila marched on Gaul. He told Ravenna that he was coming to save the Romans from the Goths and he told the Goths that he was coming to join them against the Romans. But the diplomacy of Aelius and the intelligence of Theodoric sufficed to combine Romans and Visigoths against the Hun.

Attila swept, devastating all in his path, over the Gallic frontier, with Orléans (the city of Aurelius) as his objective. Theodoric effected a junction with Aetius; Attila began to retreat, though turned near Châlons, and suffered a crushing defeat (AD 451), while Theodoric himself was killed. Though already in the next year Attila was back, this time throwing himself at Italy to enforce his demand for Honoria’s hand. Aetius, faced with a hugely superior foe, could not afford a pitched battle, leaving Atilla to destroy Aquileia, before marching on Rome. Tradition says that Attila was finally overawed by Pope Leo, another story says that the plague broke out in his camp, at any rate, Rome was miraculously delivered from the Hun as he suddenly withdrew without a fight.

In 453 Attila died and the whole terrifying, flimsy fabric of his empire dissolved. the Huns were helpless without a head. Ostrogoths, Gepids, Rugians, Herulians arose and overwhelmed them at the battle of Nedao in Pannonia in AD 454.

Aetius, often referred to as ‘the last of the Romans’, met with the same reward as Stilicho the Vandal. The mind of the emperor was poisoned against him and he was charged with treason and was slain by emperor Valentinian III himself in AD 455.

Flavius Petronius Maximus – “Petronius Maximus”

Reign: AD 455

When Valentinian III was murdered in the same year, Maximus bought the crown and forced the widowed Eudoxia to marry him.

Geiseric the Vandal – summoned to by the widowed empress – arrived two months later with a fleet. The mob tore Maximus limb from limb, which though did not prevent Geiseric from occupying Rome, sacking it with methodical and conscientious thoroughness, and retiring with a host of captives, including Eudoxia and her two daughters, the younger of whom he married to his son Hunseric.

Marcus Maecilius Flavius Eparchius Avitus – “Avitus”

Reign: AD 455 – 456

A few weeks later a new emperor was proclaimed by the Goths at Tolosa (Toulouse), Avitus, the lieutenant of the Aetius, who had been instrumental in forming the alliance between Romans and Goths against Attila.

Marcian in the east and Avitus in the west both threatened Geiseric , who defied them both. Avitus dispatched his armies under the generalship of Ricimer, a Sueve and grandson of the Visigoth Wallia, and Ricimer won a naval victory over the Vandals.

Meanwhile Theodoric II, posing as imperial champion, attacked the Sueves in Spain, breaking but not destroying their power. Avitus was bound closely to the Goths, while Italy detested them – and Ricimer was a Sueve !

Avitus had to beat a hasty retreat from Italy. Ricimer set up the Roman Majorian, an officer of distinction, as emperor, and the deposed Avitus was consoled with a bishopric AD 457).

Julius Valerius Majorianus – “Majorian”

Reign: AD 457 – 461

Majorian bestowed on Ricimer the title of Patrician – in effect first minister – which had already been borne by Stilicho, Constantius and Aetius before him.

Majorian declined to be Ricimer’s puppet, but the fleet he collected against the Vandals met with disaster, giving Ricimer sufficient excuse to depose him.

In his place the puppet emperor Libius Severus was set up.

Libius Severus

Reign: AD 461 – 465

Though Libius Severus soon died and for a time there was no emperor, save Leo at Constantinople. In AD 467 Leo appointed the Greek Anthemius, son-in-law of Marcian, as western Augustus.

Procopius Anthemius – “Anthemius”

Reign: AD 467 – 472

Ricimer was placated by receiving the new emperor’s daughter to wife.

Then east and west combined to crush the Vandals who were masters of the Mediterranean. Though Geiseric once more managed to keep the upper hand and the joint Roman fleet under Basiliscus met with disaster in AD 468.

With the Vandal controlling the sea, he consequently held Mediterranean commerce at his mercy.

Meanwhile the Visigoths, under Euric, were bringing southern Gaul under their control. Britain had slipped away, Jutes and Saxons taking a grip of her. The same fate was befalling northern Gaul. To the east of Gaul the Burgundian kingdom was gathering ever more strength.

In AD 472 Ricimer resolved to depose Anthemius, having proclaimed Olybrius (husband of the elder daughter of Valentinian III) emperor in his place.

Anicius Olybrius – “Olybrius”

Reign: AD 472

Anthemius was captured and put to death. But within a few weeks Ricimer himself died.

For a time his place was taken by his Burgundian nephew Gundobad. Olybrius died, and after some delay in AD 473 Gundobad set up a puppet emperor, Glycerius, whom Leo in Constantinople declined to recognize.

Glycerius

Reign: 473 – 474

So Gundobad returned to Burgundy and Leo proclaimed Julius Nepos emperor in AD 474.

Julius Nepos

Reign: AD 474 – 480

Though already the following year Julius Nepos was a fugitive from Rome, ejected by his ‘master of the soldiers’, Orestes, who made his own son, contemptuously known as Romulus ‘Augustulus’, emperor.

Romulus Augustus

Reign: AD 475 – 476

At the same time Zeno, the successor to Leo, was a fugitive from Constantinople, ejected by Basiliscus. Both usurpers fell in AD 476. In the east Zeno was restored, but in the west the Germanic mercenary Odoacer seized power.

Odoacer chose not to be Augustus himself, nor to serve another western Augustus, but to be the viceroy of one Roman emperor in Constantinople.

The western Roman empire had ceased to be.

The Collapse Chronology

- AD 337 May 22, death of Constantine the Great

- 337 Division of the empire between Constantine’s three sons: Constantine II (west), Constans (middle), Constantius (east). Execution of all other princes of royal blood, but for the children Gallus and Julian.

- 338 Constantius attends to the war against Persia. First unsuccessful siege of Nisibis by Sapor II

- 340 Constans and Constantine II at war. Battle of Aquileia; death of Constantine II.

- 344 Persian victory at Singara

- 346 Second unsuccessful siege of Nisibis by Sapor II

- 350 Third siege of Nisibis. Owing to incursions of the Massagetae in Transoxiana, Sapor II makes truce with Constantius.

Magnentius murders Constans and becomes emperor in the west. Vetranio proclaimed emperor on the Danube frontier. On appearance of Constantius, Vetranio resumes allegiance. - 351 Magnetnius defeated at the very bloody Battle of Mursa. Misrule by Gallus, left as Caesar in the east.

- 352 Italy recovered. Magnentius in Gaul.

- 353 Final defeat and death of Magnentius

- 354 Execution of Gallus. Julian at Athens

- 356 Julian dispatched as Caesar to Gaul. War with teh Alemanni, Quadi and Sarmatians. Military achievements by Julian.

- 357 Challenge by Sapor II

- 359 Sapor II invades Mesopotamia. Constantius goes to the east.

- 360 The Gallic army forces Julian to revolt. Julian marches down the Danube to Moesia.

- 361 Constantius dies. Julian the Apostate emperor.

- 362 Christians forbidden to teach. Julian’s advance against Persians

- 363 Disaster and death of Julian. Retreat of the army which proclaims Jovian emperor. Humiliating peace with Persia. Renewed toleration decree.

- 364 Jovian nominates Valentinian and dies.

Valentinian associates his brother Valens as eastern emperor and takes the west for himself. Permanent duality of the empire inaugurated. - 366 Damasus pope. Social and political influences become a feature of papal elections.

- 367 Valentinian sends his son Gratian as Augustus to Gaul. Theodosius the elder in Britain.

- 368 War of Valens with Goths

- 369 Peace with Goths

- 369-377 Subjugation of Ostrogoths by Hun invasion

- 374 Pannonian War of Valentinian. Ambrose Bishop of Milan

- 375 Death of Valentinian. Accession of Gratian, who associates his infant brother Valentinian II at Milan. Gratian first emperor to refuse the office of Pontifex Maximus. Theodosius the elder in Africa.

- 376 Execution of elder and retirement of younger Theodosius.

- 377 Valens receives and settles Visigoths in Moesia.

- 378 Gratian defeats Alemanni. Rising of Visigoths. Valens killed at disaster at Adrianople.

- 380 Gratian nominates the younger Theodosius as successor to Valens.

- 382 Treaty of Theodosius with Visigoths

- 383 Revolt of Maximus in Britain. Flight and death of Gratian. Theodosius recognizes Maximus in the west and Valentinian II at Milan.

- 386 Revolt of Gildo in Africa

- 387 Theodosius crushes Maximus, makes Arbogast the Frank master of the soldiers to Valentinian II

- 392 Murder of Valentinian II. Arbogast sets up Eugenius.

- 394 Fall of Arbogast and Eugenius. Theodosius makes his younger son Honorius western Augustus, with the Vandal Stilicho master of the soldiers.

- 395 Theodosius dies. Arcadius and Honorius emperors.

- 396 Alaric the Visigoth overruns Balkan peninsula.

- 397 Alaric checked by Stilicho, is given Illyria.

- 398 Suppression of Gildo in Afrca

- 402 Alaric invades Italy, checked by Stilicho

- 403 Alaric retires after defeat at Pollentia.

Ravenna becomes imperial headquarters. - 404 Martyrdom of Telemachus ends gladiatorial shows.

- 405-406 German band under Radagaesus invades Italy but is defeated at Faesula

- 406/407 Alans, Sueves and Vandals invade Gaul

- 407 Revolt of Constantine III who withdraws the troops from Britain to set up a Gallic empire

- 408 Honorius puts Stilicho to death

Theodosius II (aged 7) succeeds Arcadius.

Alaric invades Italy and puts rome to ransom - 409 Alaric proclaims Attalus emperor.

- 410 Fall of Attalus. Alaric sacks Rome but dies.

- 411 Athaulf succeeds Alaric as King of the Visigoths.

Constantine III crushed by Constantius - 412 Athaulf withdraws from Italy to Narbonne

- 413 Revolt and collapse of Heraclius

- 414 Athaulf attacks the barbarians in Spain Pulcheria regent for her brother Theodosius II

- 415 Wallia succeeds Athaulf

- 416 Constantius the patrician marries Placidia

- 417 Visigoths establish themselves in Aquitania

- 420 Ostrogoths settled in Pannonia 425 Honorius dies. Valentinian III emperor. Placidia regent.

- 427 Revolt of Boniface in Africa

- 429 The Vandals, invited by Boniface, migrate under Geiseric from Spain to Africa, which they proceed to conquer.

- 433 Aetius patrician in Italy

- 434 Rugila king of the Huns dies; Attila succeds.

- 439 Geiseric takes Carthage. Vandal fleet dominant.

- 440 Geiseric invades Sicily, but is bought off.

- 441 Attila crosses Danube and invades Thrace

- 443 Attila makes terms with Theodosius II. Burgundians settled in Gaul.

- 447 Attila’s second invasion

- 449 Attila’s second peace.

- 450 Marcian succeeds Theodosius II. Marcian stops Hun tribute.

- 451 Attila invades Gaul. Attila heavily defeated by Aetius and Theodoric I the Visigoth at Châlons

- 452 Attila invades Italy but spares Rome and retires

- 453 Attila dies. Theodoric II King of the Visigoths

- 454 Overthrow of the Hun power by the subjected barbarians at the Battle of Netad.

Murder of Aetius by Valentinian III - 455 Murder of Valentinian III and death of Maximus, his murderer. Geiseric sacks Rome, carrying of Eudoxia. Avitus proclaimed emperor of the Visigoths

- 456 Domination of both east and west by the masters of the soldiers, Aspar the Alan and Ricimer the Sueve.

- 457 Ricimer deposes Avitus and makes Majorian emperor. Marcian dies. Aspar makes Leo emperor.

- 460 Destruction of Majorian’s fleet off Cartagena.

- 461 Deposition and death of Majorian. Libius Severus emperor.

- 465 Libius Severus dies. Ricimer rules as patrician. Fall of Aspar.

- 466 Euric, King of the Visigoths, begins conquest of Spain.

- 467 Leo appoints Anthemius western emperor

- 468 Leo sends great expedition under Basiliscus to crush Geiseric, who destroys it.

- 472 Ricimer deposes Anthemius and set up Olybrius. Death of Ricimer and Olybrius.

- 473 Glycerius western emperor

- 474 Julius Nepos western emperor. Leo dies and is succeeded by his infant grandson Leo II. Leo II dies and is succeeded by Zeno the Isaurian

- 475 Romulus Augustus last western emperor.

Usurpation of Basiliscus at Constantinople. Zeno escapes to Asia. Theodoric the Amal becomes King of the Ostrogoths - AD 476 Odoacer the Scirian, commander and elected King of the German troops in Italy, deposes Romulus Augustus and resolves to rule independently, but nominally as the viceroy of the Roman Augustus of Constantinople.

End of the western empire.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.