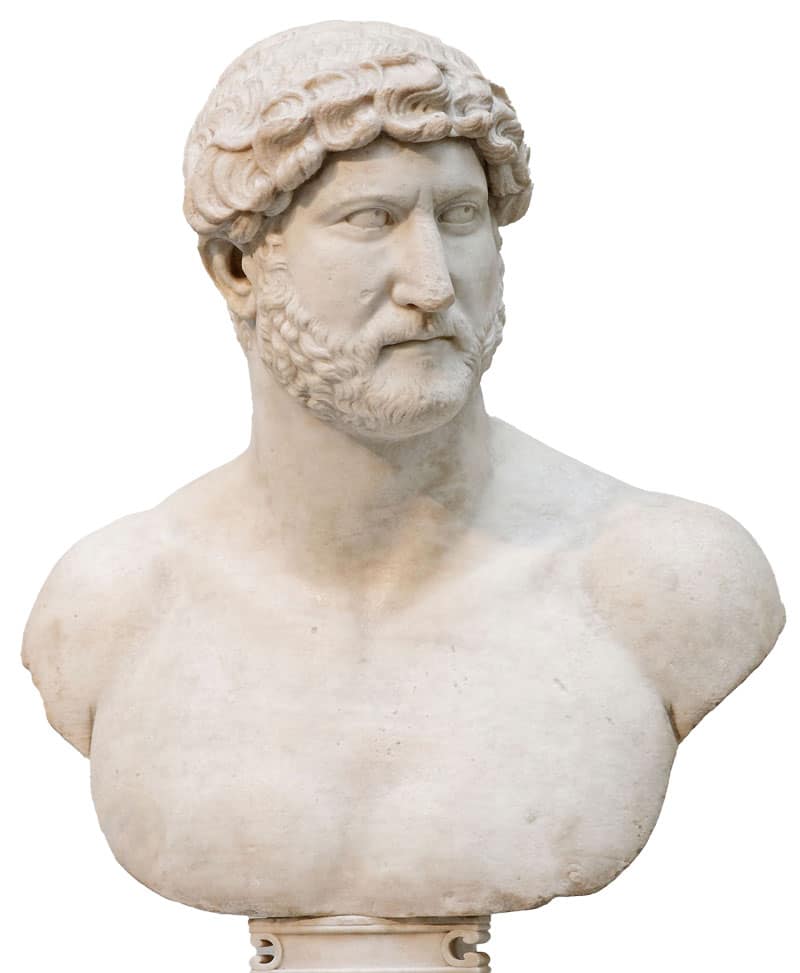

Life: AD 76 – 138

- Name: Publius Aelius Hadrianus

- Born on 24 January AD 76 in Rome.

- Consul AD 108, 118, 119.

- Became emperor on 11 August AD 117.

- Wife: Vibia Sabina.

- Died at Baiae, 10 July AD 138.

The Early Life of Emperor Hadrian

Publius Aelius Hadrianus was born on 24 January AD 76, probably in Rome, though his family lived in Italica in Baetica. Having originally come from Picenum in the northeastern when this part of Spain was opened up to Roman settlement, his family had lived in Italica for some three centuries. With Trajan also coming from Italica, and Hadrian’s father, Publius Aelius Hadrianus Afer, being his cousin, Hadrian’s obscure provincial family now found itself possessing impressive connections.

Hadrian’s Ascension to Power

In AD 86 Hadrian’s father died, and he, at the age of 10, became a joint ward of Acilius Attianus, a Roman equestrian, and of Trajan. Trajan’s initial attempt to create a military career for the 15-year-old Hadrian was frustrated by Hadrian’s liking the easy life. He preferred going hunting and enjoying other civilian luxuries. And so Hadrian’s service as a military tribune stationed in Upper Germany ended with little distinction as Trajan angrily called him to Rome in order to keep a close eye on him.

Next, the so far disappointing young Hadrian was set on a new career path. This time – though still very young – as a judge in an inheritance court in Rome. And alas he shortly afterward succeeded as a military officer in the Second Legion ‘Adiutrix’ and then in the Fifth Legion ‘Macedonia’ on the Danube. In Ad 97 when Trajan, based in Upper Germany was adopted by Nerva, it was Hadrian who was sent from his base to carry the congratulations of his legion to the new imperial heir.

But in AD 98 Hadrian seized the great opportunity of Nerva’s to carry the news to Tajan. Utterly determined to be the first to carry this news to the new emperor he raced to Germany. With others also seeking to be the bearers of the good news to a no doubt grateful emperor it was quite a race, with many an obstacle being purposely placed in his way. But he succeeded, even traveling the last stages of his journey on foot. Trajan’s gratitude was assured and Hadrian indeed became a very close friend of the new emperor.

The Marriage of Emperor Hadrian

In AD 100 he married Vibia Sabina, the daughter of Trajan’s niece Matidia Augusta, after having accompanied the new emperor to Rome. Soon after followed the first Dacian war, during which time Hadrian served as quaestor and staff officer.

With the second Dacian war following soon after the first, he was given command of the First Legion ‘Minerva’, and once he returned to Rome he was made praetor in AD 106. A year thereafter he was governor of Lower Pannonia and then consul in AD 108.

Hadrian’s Rule: A Period of Expansion and Consolidation

When Trajan embarked on his Parthian campaign in AD 114, Hadrian once more held a key position, this time as governor of the important military province of Syria. There is no doubt that Hadrian was of high status during Trajan’s reign, and yet there were no immediate signs that he was intended as the imperial heir. The details of the succession are indeed mysterious. Trajan might well have decided on his deathbed to make Hadrian his heir.

But the sequence of events does indeed seem suspicious. Trajan died on the 8 August AD 117, on the 9th it was announced at Antioch that he had adopted Hadrian. But only by the 11th was it made public that Trajan was dead. According to the historian Dio Cassius, Hadrian’s accession was solely due to the actions of Empress Plotina, who kept Trajan’s death a secret for several days. In this time she sent letters to the senate declaring Hadrian the new heir. This letter however carried her own signature, not that of Emperor Trajan, probably using the excuse that the emperor’s illness made him too feeble to write.

Yet another rumor asserted that someone had been sneaked into Trajan’s chamber by the empress, in order to impersonate his voice. Once the accession was secure, and only then, did Empress Plotina announce Trajan’s death. Hadrian, already in the east as governor of Syria at the time, was present at Trajan’s cremation at Seleucia (the ashes were thereafter shipped back to Rome). Though now he was there as emperor.

Right from the start, the new Emperor made it clear that he was his own man. One of his very first decisions was the abandonment of the eastern territories that Trajan had just conquered during his last campaign. Had Augustus a century before spelled out that his successors should keep the empire within the natural boundaries of the rivers Rhine, Danube, and Euphrates, then Trajan would have broken that rule and crossed the Euphrates. On Hadrian’s order once pulled back to behind the Euphrates again.

Such withdrawal, the surrendered territory for which the Roman army had just paid in blood, would hardly have been popular. He did not travel directly back to Rome but first set out for the Lower Danube to deal with trouble with the Sarmatians at the border. While he was there he also confirmed Trajan’s annexation of Dacia. The memory of Trajan, the Dacian gold mines, and the army’s misgivings about withdrawing from conquered lands clearly convinced him that it might not be wise always to withdraw behind the natural boundaries advised by Augustus.

If Hadrian set out to rule as honorably as his beloved predecessor, then he got off to a bad start. He had not arrived in Rome yet and four respected senators, all ex-consuls, were dead. Men of the highest standing in Roman society, all had been killed for plotting against the Emperor. Many however saw these executions as a way by which Hadrian was removing any possible pretenders to his throne. All four had been friends of Trajan. Lucius Quietus had been a military commander and Gaius Nigrinus had been a very wealthy and influential politician; in fact so influential he had been thought a possible successor to Trajan.

But what makes the ‘affair of the four consuls, especially unsavory is that Hadrian refused to take any responsibility for this matter. Might other emperors have gritted their teeth and announced that a ruler needed to act ruthlessly in order to grant the empire a stable, unshakable government, then Hadrian denied everything. He even went as far as swearing a public oath that he was not responsible. More so he said that it had been the senate who had ordered the executions (which is technically true), before placing the blame firmly on Attianus, the praetorian prefect (and his former join-guardian with Trajan).

However, if Attianus had done anything wrong in the eyes of Hadrian, it is hard to understand why the emperor would have made him consul thereafter. Despite such an odious start to his reign, Hadrian quickly proved to be a highly capable ruler. Army discipline was tightened and the border defenses were strengthened. Trajan’s welfare program for the poor, the alimenta, was further expanded. Most of all though, Hadrian should become known for his efforts to visit the imperial territories personally, where he could inspect the provincial government himself.

These far-ranging journeys would begin with a visit to Gaul in AD 121 and would end ten years later on his return to Rome in AD 133-134. No other emperor would ever see this much of his empire. From as far west as Spain to as far east as the province of Pontus in modern-day Turkey, from as far north as Britain to as far south as the Sahara desert in Libya, Hadrian saw it all. Though this was not mere sight-seeing. Furthermore, he sought to gather first-hand information about the various problems the provinces faced. His secretaries compiled entire books of such information.

Perhaps the most famous result of Hadrian’s conclusions when seeing for himself the problems faced by the territories, was his order to construct the great barrier which still today runs across northern England, Hadrian’s Wall, which once shielded the British Roman province from the wild northern barbarians of the isle.

Architectural Contributions and Love for Greek Culture

Since a very young age, he had held a fascination for Greek learning and sophistication. So much so, that he was dubbed the ‘Greekling’ by his contemporaries. Once he became emperor his tastes for all things Greek should become a trademark of his. He visited Athens, still the great center of learning, no fewer than three times during his reign. And his grand building programs did not limit themselves to Rome with a few grand buildings in other cities, but also Athens benefitted extensively from its great imperial patron.

Controversies and Scandals During Reign

Yet even this great love of art should become sullied by Hadrian’s darker side. Had he invited Trajan’s architect Apollodorus of Damascus (the designer of Trajan’s Forum) to comment on his own design for a temple, he then turned on him, once the architect showed himself little impressed. Apollodorus was first banished and later executed. Had great emperors shown themselves able to handle criticism and listen to advice, then Hadrian who at times patently was unable, or unwilling, to do so.

Hadrian appears to have been a man of mixed sexual interests. The Historia Augusta criticizes both his liking of good-looking young men as well as his adultery with married women. If his relationship with his wife was anything but close, then the rumor that he tried to poison her might suggest that it was even much worse than that.

When it comes to his apparent homosexuality, then the accounts remain vague and unclear. Most of the attention centers on the young Antinous, whom he grew very fond of. Statues of Antinous have survived, showing that imperial patronage of this youth extended to having sculptures made of him. In AD 130 Antinous accompanied Hadrian to Egypt. It was on a trip on the Nile when Antinous met with an early and somewhat mysterious death. Officially, he fell from the boat and drowned. But a persistent rumor spoke of Antinous having been a sacrifice in some bizarre eastern ritual.

The reasons for the young man’s death might not be clear, but what is known is that he grieved deeply for Antinous. He even founded a city along the banks of the Nile where Antinous had drowned, Antinoopolis. Touching as this might have seemed to some, it was an act deemed unbefitting an emperor and drew much ridicule.

The Jewish Revolt

If the founding of Antinoopolis had caused some eyebrows to be raised then Hadrian’s attempts to re-found Jerusalem were little more than disastrous.

Had Jerusalem been destroyed by Titus in AD 71 then it had never been rebuilt since. At least not officially. And so, Hadrian, seeking to make a great historical gesture, sought to build a new city there, to be called Aelia Capitolina. Hadrian planned a grand imperial Roman city, it was to boast a grand temple to Jupiter Capitolinus on the temple mount.

The Jews, however, found it hard to stand by and watch in silence while the emperor desecrated their holiest place, the ancient site of the Temple of Salomon. And so, with Simeon Bar-Kochba as its leader, an embittered Jewish revolt arose in AD 132. Only by the end of AD 135 was the situation back under control, with over half a million Jews having lost their lives in the fighting. This might have been his only war, and yet it was a war for which only really one man could be blamed – emperor Hadrian.

However, it must be added that the troubles surrounding the Jewish insurrection and its brutal crushing were unusual in Hadrian’s reign. His government was, but for this occasion, moderate and careful.

Influence on Roman Law

Hadrian showed a great interest in law and appointed a famous African jurist, Lucius Salvius Julianus, to create a definitive revision of the edicts which had been pronounced every year by the Roman praetors for centuries.

This collection of laws was a milestone in Roman law and provided the poor with at least a chance to gain some limited knowledge of the legal safeguards to which they were entitled.

The Succession Crisis During Hadrian’s Final Years

In AD 136 Hadrian, whose health began to fail, sought an heir before he would die, leaving the empire without a leader. He is 60 years old now. Perhaps he feared that being without an heir might make him vulnerable to a challenge to the throne as he grew more frail. Or he simply sought to secure a peaceful transition for the empire. Whichever version is true, Hadrian adopted Lucius Ceionius Commodus as his successor.

Once more the more menacing side of Hadrian showed as he ordered the suicide of those he suspected opposed to Commodus’ accession, most notably the distinguished senator and Hadrian’s brother-in-law Lucius Julius Ursus Servianus. The chosen heir, though only in his thirties, suffered from bad health and so Commodus was already dead by 1 January AD 138.

A month after Commodus’ death, Hadrian adopted Antoninus Pius, a highly respected senator, on the condition that the childless Antoninus in turn would adopt Hadrian’s promising young nephew Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus (the son of Commodus) as heirs.

His final days were a grim affair. He became even more ill and spent extended periods in severe distress. As he sought to end his life with either a blade or poison, his servants grew ever more vigilant to keep such items from his grasp. At one point he even convinced a barbarian servant by the name of Mastor to kill him. But at the last moment, Mastor failed to obey.

Despairing, Hadrian left government in the hands of Antoninus Pius, and retired, dying soon afterwards at the pleasure resort of Baiae on 10 July AD 138.

The Legacy

Had Hadrian been a brilliant administrator and had he provided the empire with a period of stability and relative peace for 20 years, he died a very unpopular man. He had been a cultured man, devoted to religion, law, and the arts – devoted to civilization. And yet, he also bore that dark side in him which could reveal him as similar to a Nero or a Emperor Domitian at times. And so he was feared. And feared men are hardly ever popular.

His body was buried twice in different places before finally his ashes were laid to rest in the mausoleum he had built for himself in Rome. It was only with reluctance that the senate accepted Antoninus Pius’ request to deify the dead Emperor.

People Also Ask:

1. Who was Emperor Hadrian?

- He was a Roman Emperor who reigned from 117 to 138 AD. He is known for his substantial building projects throughout the Roman Empire and for consolidating and fortifying its borders.

2. What are Hadrian’s most notable achievements?

- His most famous construction is Hadrian’s Wall in Britain, built to mark the northern limit of Roman territory. He also rebuilt the Pantheon in Rome and constructed Hadrian’s Villa near Tivoli.

3. Was Hadrian a military leader?

- Yes, he served as a military leader before becoming emperor. He is recognized for his efforts to strengthen the Roman military and for adopting a defensive strategy for the empire.

4. How did Hadrian impact Roman culture?

- Hadrian was a patron of the arts and culture. He promoted the spread of Hellenistic culture throughout the empire and was an avid admirer of Greek architecture and philosophy.

5. What was Hadrian’s approach to governance?

- Hadrian is known for his administrative efficiency and efforts to humanize the laws. He traveled extensively, visiting almost every province of the Empire to inspect and improve local governance.

6. Did Hadrian face any significant challenges during his reign?

- Yes, he faced several military challenges, including a major Jewish rebellion led by Simon Bar Kokhba in Judea. This revolt was brutally suppressed by the Roman forces.

7. How did Hadrian’s reign end?

- He died in 138 AD after a prolonged illness. He was succeeded by Antoninus Pius, whom he had adopted as his heir.

8. What is Hadrian’s legacy?

- His legacy lies in his efforts to consolidate the Empire, his architectural achievements, and his promotion of Hellenistic culture. His reign is often seen as a high point in the Pax Romana, a period of relative peace and stability in the Roman Empire.

9. Are there any major sources for studying Hadrian’s life?

- Key sources include the ancient historian Cassius Dio and the ‘Historia Augusta’, a collection of Roman biographies. Archaeological findings, including inscriptions and coins, also provide valuable insights.

10. Can I visit any of Hadrian’s constructions today?

- Yes, many of his constructions, such as Hadrian’s Wall and the Pantheon, are well-preserved and open to visitors.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.