Siege Warfare – Tactics

Ancient Romans were experts in siege warfare. In conducting sieges, the Romans showed their practical genius combined with ruthless thoroughness. If a place could not be overcome by the initial assaults or the inhabitants were persuaded to surrender, it was a practice of the Roman army to surround the whole area with a defensive wall and ditch and spread their units around these fortifications. This ensured no supplies and reinforcements got to the besieged, as well as guarding against any sorties of an attempt to break out.

There are several examples of efforts being made to cut off the water supply. Caesar was able to take Uxellodunum by concentrating on this target. First, he stationed archers who maintained a steady fire on the water carriers who went to draw from the river which ran round the foot of the hill on which the citadel stood. The besieged then had to rely entirely on a spring at the foot of their wall. But Caesar’s engineers were able to undermine the spring and draw the water off at a lower level, thus forcing the town to surrender.

Siege Warfare – Engines

Siege weapons were varied and ingenious inventions, their main object being to effect an entrance through the gates or walls. Gateways were usually the most heavily defended positions so it was often better to select a point along the walls. First, however, the ditches had to be filled with hard-packed material to allow the heavy machinery to approach the foot of the wall.

The soldiers manning the wall would try to prevent this by firing their missiles at the working party. To counteract this the attackers were provided with protective screens (musculi), which were lined with iron plates or hides. The musculi provided some protection but not hardly enough. So, constant fire had to be directed against the men on the wall to harass them. This was managed by bringing up stout timber towers higher than the wall so that men on their tops could pick off the defenders.

A model of a Roman siege tower at the Museo della Civilta in Rome is a typical example of Roman siege warfare. This colossal tower on wheels would mainly be used to provide height for archers and ballista catapults. From this vantage point, they would be able to fire their arrows and bolts at the men atop a city’s walls and turrets, thus allowing the Roman soldiers to work on creating a hole in the wall without being attacked from above.

This particular model even has the ram built into its base so that the soldiers operating it can work within the safety of the tower.

Siege Warfare – Ram

The ram was a heavy iron head in the shape of a ram’s head fixed to a massive beam which was constantly slung against a wall or gate until it was breached. There was also a beam with an iron hook, which was inserted into a hole in the wall made by the ram and with which stones would be dragged out. Further, there was a smaller iron point (terebus) used for dislodging individual stones.

The beam and frame from which it was swung were enclosed in a very strong shed covered with hides or iron plates mounted on wheels. This was called a tortoise (testudo arietaria) since it resembled this creature with its heavy shell and head that moved in and out.

Under the protection of the towers, most likely in protective sheds, gangs of men worked at the foot of the wall, making holes through it or digging down to get underneath it. Excavating galleries under the defenses was common practice. The purpose was to weaken walls or towers at the foundations so that they collapsed. This was, of course, much more difficult to do without the enemy becoming aware of it. One may say the ram was a real breakthrough for siege warfare.

At the siege of Marseille, the defenders countered attempts to tunnel under their walls by digging a large basin inside the walls, which they filled with water. When the mines approached the basin, the water flowed out, flooding them and causing them to collapse. The only defense against Roman’s massive siege engines was to destroy them either by fire missiles or by sorties made by a small, desperate body of men who’d try to set fire to them or turn them over.

Siege Warfare – Catapults

The Roman army used several types of powerful siege warfare weapons for discharging missiles. The largest was the onager (the wild ass because of the way it kicked out when it fired). Or so it was called from the late third century AD onwards. When being moved with a legion, it would be on a wagon in its dismantled state, pulled by oxen.

The Onager

Above is a reconstructed, complete onager of the Ermine Street Guard in the UK (Legio XX Valeria Victrix), on display at Birdoswald Fort (Hadrian’s Wall) in May 2007. Although only loosely strung, this onager fired a stone ball 30 to 40 yards.

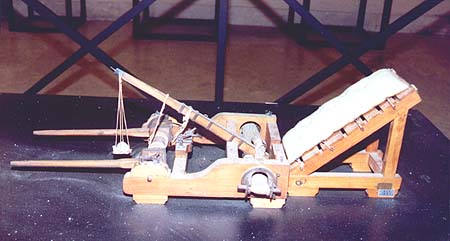

Below is a model of an onager catapult at the Museo della Civilta in Rome. This machine would be the heavy artillery of the ancient world. The handles to the left (rear of the catapult) are, in fact, levers by which the soldiers would wind the throwing arm back.

On the right, you see a cushion at the front of the catapult. No doubt it was there to soften the blow of the throwing and help to prevent the machine from tearing itself apart.

Apparently, there was an earlier version of this catapult known as the scorpion (Scorpio), although this was a considerably smaller, less powerful machine. Onagri were used in sieges to batter down walls, as well as by defenders to smash siege towers and siege works. This explains their use as defensive batteries in cities and fortresses of the late empire. The stones they hurled naturally were also effective when used against the densely packed lines of enemy infantry.

Another infamous catapult of the Roman army was the ballista. In essence, it was a large crossbow, which could fire either arrows or stone balls. Various shapes and sizes of ballistas were around.

Firstly, there was the large basic ballista, most likely used as a siege engine to fire stones, before the introduction of the onager-type catapults. It would have a practical range of about 300 meters and would be operated by about 10 men.

Siege Warfare – The Ballista

The Ballista

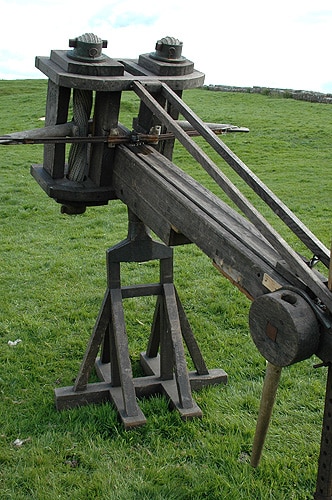

Left: A reconstructed, complete ballista of the Ermine Street Guard in the UK (Legio XX Valeria Victrix), on display at Birdoswald Fort (Hadrian’s Wall) in May 2007. Although only loosely strung, this ballista fired a stone ball 30 to 40 yards, reaching a very great height.

Right: the torsion mechanism of the ballista’s right arm. The twisted ropes provide the power that propels the arms; the greater the twist, the greater the power.

There were more nimble, smaller sizes, including one dubbed the scorpion (Scorpio), which would fire large arrow bolts. Also, there was the carro-ballista, which essentially was a scorpion-sized ballista mounted on wheels or a cart, which could therefore, rapidly be moved from one place to another – no doubt ideal for a battlefield.

The most likely use for the bolt-firing scorpio and carro-ballista would be on the flanks of the infantry. Used in much the same way as modern machine guns, they could fire across the heads of their own troops into the enemy. The large bolts varied in length and size and were equipped with various types of iron heads, from simple sharp tips to crested blades. When on the march, these mid-range catapults would be loaded on wagons and then drawn along by mules.

Other, more strange versions of the ballista existed.

The Scorpio-Ballista

A photo of a recreated Roman ballista-type ‘Scorpion’ catapult. In essence, it’s much the same but smaller than a basic ‘ballista’. However, this machine was devised as a piece of field artillery. Unlike the full-sized ballista which was a siege warfare engine firing stone balls, the Scorpio supported Roman infantry on the battlefield by firing bolts at the enemy.

The manu-ballista, a small crossbow based on the same principle as the ballista, could be held by one man. No doubt, it could be seen as the forerunner of the hand-held medieval crossbow.

Further, there has also been some research done into the existence of the self-loading, serial-fire ballista. Legionaries on either side would continuously keep turning cranks which turned a chain, which operated the various mechanisms to load and fire the catapult. All that was needed was for another soldier to keep feeding in more arrows. The estimates regarding the numbers of these siege warfare machines that a legion would have to draw on are wide-ranging.

On one hand, it is said that each legion had ten onagri, one for each cohort. Apart from this, each century was also allocated a ballista (most likely of the scorpion or carro-ballista variety). However, other estimates suggest that these engines were anything but widespread and that Rome relied more on the ability of its soldiery to decide matters. And when used by legions on a campaign, the catapults had simply been borrowed from forts and city defenses. Hence, there would be no regular spread of such machines across the troops.

It is hence, hard to establish how widespread the use of these machines truly was. One term causing confusion with these catapults is the ‘scorpion’ catapult (Scorpio). This derives from the fact that the name had two different uses.

Essentially, the catapults used by the Romans were largely Greek inventions. And one of the Greek ballista-type catapults at first appeared to be called ‘scorpion.’ However, also the smaller version of the ‘onager’ was given that name, most likely as the throwing arm, reminded of the stinging tail of a scorpion. Naturally, this causes some degree of confusion.

People also ask:

What is the siege warfare strategy?

This is the law of strategic siege warfare. So the rule for use of the military is that if you outnumber the opponent ten to one, then surround them; five to one, attack; two to one, divide. If you are equal, then fight if you are able. If youare fewer, then keep away if you are able. Without honouring this law, the siege warfare is destined for failure.

Is Siege Warfare still being used?

Siege warfare has been employed throughout the ages and remains dramatically relevant today.

What was siege warfare in the Roman Empire?

Ancient Romans were experts in siege warfare. In a typical Roman siege, if an initial attack failed to bring immediate victory, forces were sent ahead to surround the settlement and prevent anyone escaping. At the same time, as very often ancient cities were also ports, they had to be blockaded by the sea as well as land.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.